The Utterly Sad Anniversary of the “War to End All Wars”: A Look Back Through America's Historical Newspapers

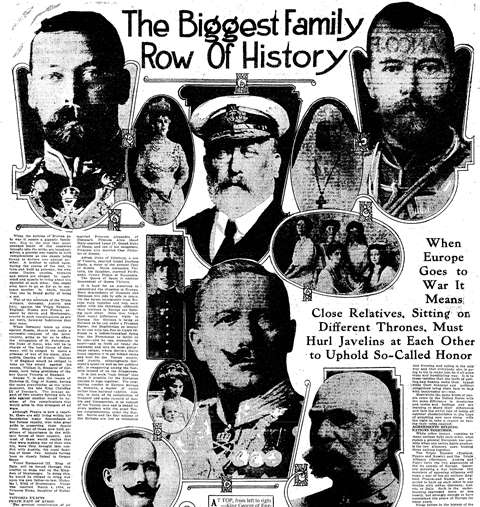

August 2014 marks the hundredth anniversary of the beginning of what we now call World War I. The wars in Europe since 1815 had been brief affairs. The expectation was that this would also be brief. The Colorado Gazette of August 23, 1914, called it “the Biggest Family Row of History.”

The war would last four years and mark the end of what some historians call the long 19th century, which they date from the French Revolution to 1914. It was the beginning of the end of several European societies; the empires of Russia, Austro-Hungary and Germany did not survive the conflict. Eastern Europe was completely reshaped politically by the war and the peace that followed it. Great Britain struggled with its economic consequences. The European conflicts of the 1930s and World War II are direct results of it, too. America’s Historical Newspapers can help students and scholars explore and understand this conflagration in new ways.

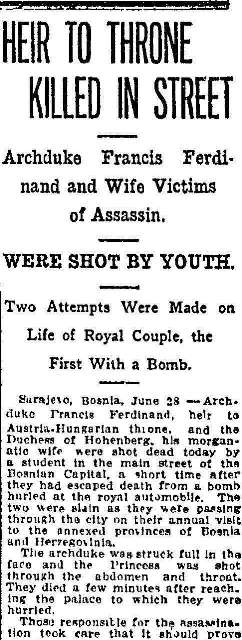

The crisis that started it actually began six weeks earlier, when the heir to the Austro-Hungarian throne, Archduke Franz Ferdinand, was assassinated by Serbian nationalists. Other European royalty and government officials had been assassinated in the three decades previous to this killing, but they did not set off a general European war. This killing of the archduke, and the death of his wife in the same attack, would.

The Charlotte Observer on June 29, 1914, headlined the story this way – “Heir to Throne Killed in Street – Archduke Francis Ferdinand and Wife Victims of Assassin – Were Shot by Youth – Two Attempts Were Made on Life of Royal Couple, the First with a Bomb.”

Historians differ on what the primary cause of the war was. The Austrian desire for revenge against the Serbs, the ineptness of diplomats, the interlocking treaties that bound all the great European powers into two competing power blocs, the Germans supporting the Austrians and the Russians and thus the French and British behind the Serbs, the timetables for calling up troops and moving them into place, and, perhaps, the egoism of some of the hereditary rulers—all played a part in dooming peace. Historians might disagree on why and how it started, but start it did. The Albuquerque Journal of August 3, 1914, reported in huge type, “Germans Invade France; Czar Invades Germany – Hope for Peace Vanishes...”

This would be the largest conflict of the machine age—until the next one. World War I combatants adapted strategies and technologies that had been used in previous wars, sizing them up to industrial scale. Trenches had been used before. The entire Western Front seemed to be trenches, from the ocean to Switzerland. The Gatling gun, a machine gun precursor, had been used in the U.S. Civil War and in colonial wars through the rest of the 19th century. The Maxim gun, which used the recoil to eject spent cartridges and reload fresh ones, dated from 1884 and had spread through Europe’s armies. The Browning machine gun, which was water cooled, was perfected in 1910. The combination of trenches and machine guns made the no-man’s-land between them a killing zone.

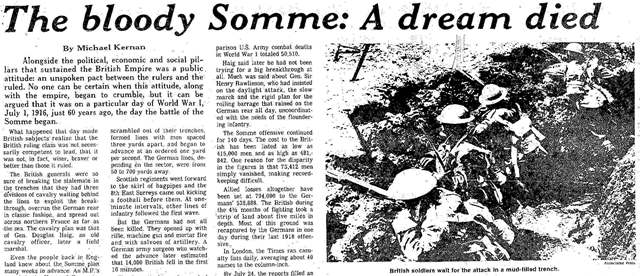

The first day of the battle of the Somme illustrates this. A June 27, 1976, article from the Cleveland Plain Dealer, written by author and journalist Michael Kernan, states that after several days of artillery barrage and a 1.5 million shells thrown by 1,437 guns,

The high command believed…there would be no Germans left alive and the advance could be made as if on parade.

“You will be able to go over the top with a walking-stick,” one British brigadier told his men….

66,000 soldiers of the British empire scrambled out of their trenches, formed lines with men spaced three yards apart, and began to advance at an ordered one yard per second….

At one-minute intervals, other lines of infantry followed the first wave.

But the Germans had not all been killed. They opened up with rifle, machine gun and mortar fire and with salvoes of artillery. A German army surgeon who watched the advance later estimated that 14,000 British fell in the first 10 minutes.

Modern estimates for this day are 57,000-plus British casualties, with over 19,000 of those killed.

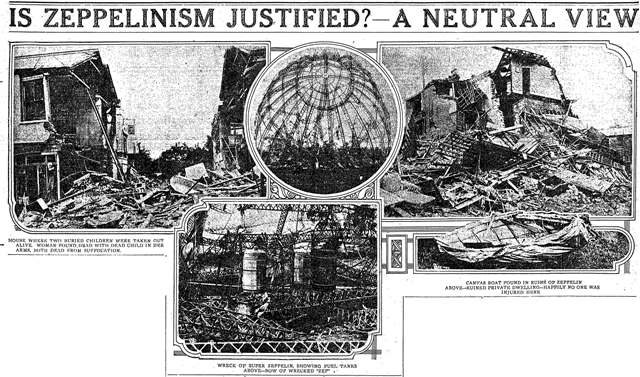

Balloons had been used for observation in the Civil War. Fixed-wing aircraft had been used for observation and to deliver air-dropped bombs in two minor wars (if any war is minor for those involved) that preceded the First World War: the Italo-Turkish War of 1911 and the first Balkan War of 1912. World War I provided the opportunity to use bombing raids to extend the front far behind battle lines. London, Paris and Warsaw were bombed by Zeppelins. In a war in which gains on the ground were measured in yards, and soldiers wore uniforms that limited their individuality, the aerial feats of specific pilots battling aloft were lionized.

A technological breakthrough in the battlefield was the development of tanks, which were used to break up the barbed wire in no-man’s-land and provide a pathway for troops to follow. Here’s a photo of one from the December 31, 1916, issue of the San Jose Mercury News.

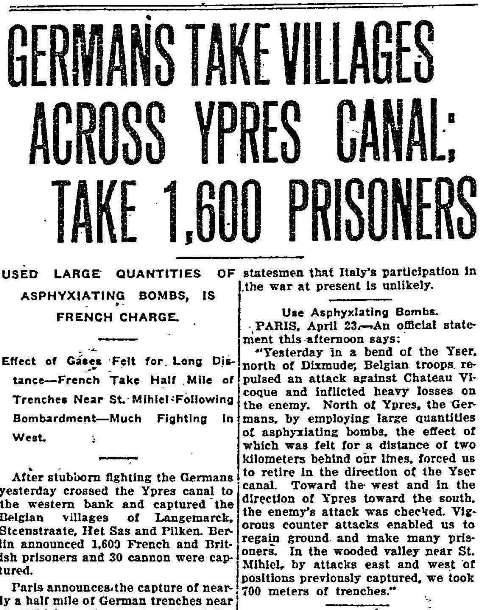

The worst “advance” in warfare was the use of poison gas, though the flamethrower might equal it. The Germans used it first at the second battle of Ypres in April of 1915. The Allies responded in kind. The second headline of this article on the battle, printed in the April 23, 1915, edition of the Olympia Daily Recorder is “Used Large Quantities of Asphyxiating Gas, Is French Charge”

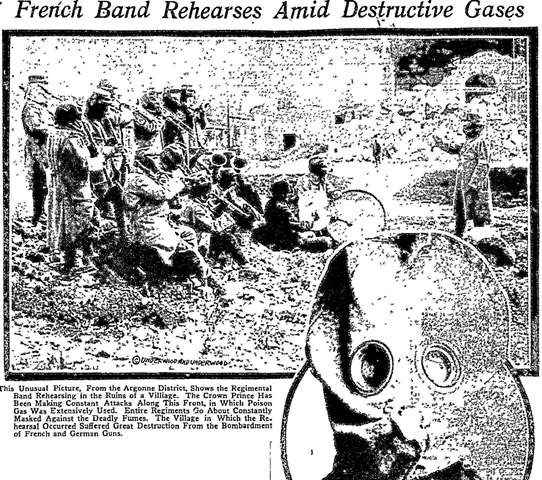

Armies on all sides were given masks to prevent the inhalation of this new weapon. Newspapers were able to provide a visual record of the conflict through the increased use of photography. Here’s a photograph of protective measures taken against gas attack by a French military band from the Philadelphia Inquirer of October 11, 1915.

This photo spread from the October 29, 1916, New Orleans Times-Picayune asks whether bombing is justified.

Newspapers also provided maps showing where the front lines were and how the battle was unfolding. This example from the Charlotte Observer of July 6, 1916, shows the front lines from the Belgian coast to Verdun.

Articles, photos, maps, illustrations and cartoons provide the researcher with the evolving action and context of the war. Sometimes the results look distant in time, like the French band practicing in gas masks. Sometimes, though, the context is so up to date as to be scary. When Turkey entered the war on the German side, they declared it a jihad. A photo from the Dec 24, 1914, Philadelphia Inquirer shows it happening.

There were two major unintended consequences to the war. One was the Spanish influenza epidemic of 1918, which is thought to have been a swine flu that jumped to humans near Camp Funston in Kansas. It is estimated to have killed 50,000,000 people worldwide, twice the number killed by the war itself. The second, thanks to the harsh peace terms agreed upon after the war, was World War II. Both events can also be fruitfully studied using America’s Historical Newspapers.

For more information about America’s Historical Newspapers, or to request a trial for your institution, please contact readexmarketing@readex.com.