From the Velvet Underground to the Velvet Revolution: Charter 77’s Redemption of Human Rights in Czechoslovakia

Take a day, and walk around.

Watch the Nazis run your town.

Then go home and check yourself.

You think we’re singing about someone else.

— Frank Zappa, “Plastic People”

Czechoslovakia’s 1989 Velvet Revolution began not with a bang, but with a band. Specifically, that band was the Plastic People of the Universe, who took their name from a song by American musician Frank Zappa. Their style falls loosely into the Western genre of art rock and was inspired by Zappa’s experimental work with the Mothers of Invention, and by Lou Reed and the Velvet Underground’s “Exploding Plastic Inevitable” multi-media collaboration with artist Andy Warhol in the mid-1960s.

In 1976 under the auspices of maintaining social standards in music, the Czechoslovak government broke-up a music festival featuring the Plastic People, confiscated their equipment, and arrested the band’s members and associates. Here’s the official response to the international outcry which accompanied that action from the Communist newspaper Rudé Právo [Red Truth], included in Readex’s World Protest and Reform Movements: Global Perspectives, 1945-1996.

The young people now tried and sentenced have for several years been performing as members of rock groups called “Plastic People of the Universe” and “DG-307.” But even the most tolerant person could not call what they performed “art.” Both the feeling of shame and the law prevents us from publishing one of their song texts, even as a sample. If we say that they are vulgar, it is an understatement. They are foul and lewd. We can take it that those who are clamoring about the “persecution” of musicians in the CSSR most assuredly know the elements in question.

Although their life behind the Iron Curtain might readily have been construed as “the Nazis” running their town—especially after their arrest—the members of the Plastic People insisted that their music wasn’t political per se. However, their audience certainly was political, and included the future President of the Czech Republic Václav Havel, who had achieved both critical success as an avant-garde playwright, and official notoriety as a dissident.

The discussions and relationships ensuing from the trial and conviction of the Plastic People of the Universe led to the drafting of Charter 77, which was a signed declaration of protest calling for the Czechoslovak government to live up to its own treaty obligations for the protection of civil and human rights under the Conference on Security and Cooperation in Europe (CSCE)’s Helsinki Final Act of 1975.

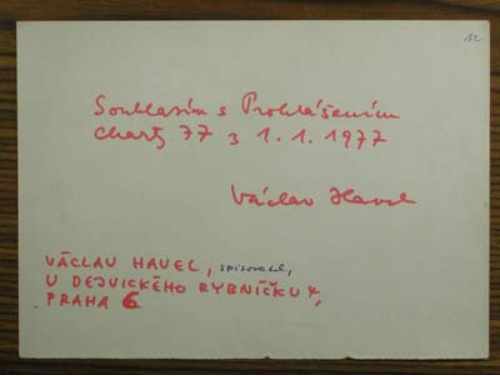

Havel was one of the initial signatories of Charter 77. His association with the document was extremely dangerous; he was harassed, arrested, and served multiple prison sentences before he was elected President in 1993.

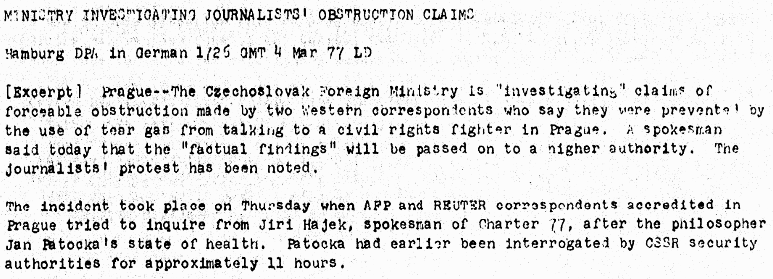

Shortly after the creation of Charter 77, fellow signatory and sponsor of the document, 70-year-old Professor Dr. Jan Patočka, was likewise arrested and died following an eleven-hour police interrogation. The following excerpt from the West German Deutsche Presse-Agentur [German News Agency (DPA)] shows how seriously the world press took the Czechoslovak government’s repression of the proponents of Charter 77, as it describes how journalists from Agence France-Presse and Reuters were tear gassed in their quest to follow the story:

The Czechoslovak Foreign Ministry is “investigating” claims of forceable obstruction made by two Western correspondents who say they were prevented by the use of tear gas from talking to a civil rights fighter in Prague. A spokesman said today that the “factual findings” will be passed on to a higher authority. The journalists’ protest has been noted.

The incident took place on Thursday when AFP and REUTER correspondents accredited in Prague tried to inquire from Jiri Hajek, spokesman of Charter 77, after the philosopher Jan Patocka’s state of health. Patocka had earlier been interrogated by CSSR security authorities for approximately 11 hours.

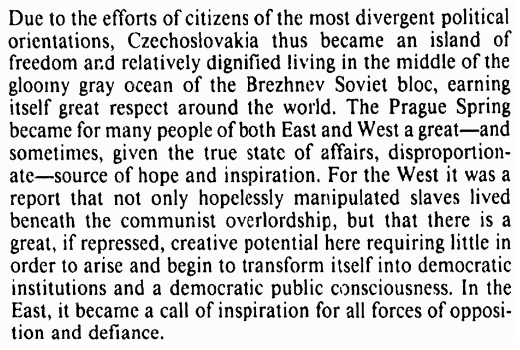

Havel traced his country’s reemergence from behind the Iron Curtain back to the Prague Spring rebellion of 1968 and the subsequent invasion of the country by Warsaw Pact members.

The Plastic People were also founded during that brief period of liberalization under First Secretary Alexander Dubček, and served as a reminder both of what was possible and what was lost under the treads of communist tanks. Journalists from the Czech News Agency (CTK), the source of the excerpt below, supported the 1968 reforms until they too were forced to conform with communist orthodoxy.

Due to the efforts of citizens of the most divergent political orientations, Czechoslovakia thus became an island of freedom and relatively dignified living in the middle of the gloomy gray ocean of the Brezhnev Soviet bloc, earning itself great respect around the world. The Prague Spring became for many people of both East and West a great—and sometimes, given the true state of affairs, disproportionate—source of hope and inspiration. For the West it was a report that not only hopelessly manipulated slaves lived beneath the communist overlordship, but that there is a great, if repressed creative potential here requiring little in order to arise and begin to transform itself into democratic institutions and a democratic public consciousness. In the East, it became a call of inspiration for all forces of opposition and defiance.

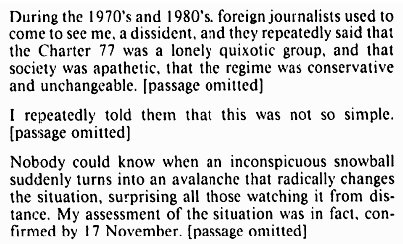

Charter 77 was thus an ideological vote of confidence for the liberation of that “creative potential” and a vote of no confidence in the “communist overlordship.” Despite the popular undercurrent in favor of democratic institutions in Czechoslovakia, in the following transcript from Czech Radiožurnál Havel notes that change did not come overnight.

During the 1970's and 1980's foreign journalists used to come to see me, a dissident, and they repeatedly said that the Charter 77 was a lonely quixotic group, and that society was apathetic, that the regime was conservative and unchangeable. [passage omitted]

I repeatedly told them that this was not so simple. [passage omitted]

Nobody could know when an inconspicuous snowball suddenly turns into an avalanche that radically changes the situation, surprising all those watching it from distance. My assessment of the situation was in fact confirmed by 17 November [1989].

One dramatic expression of this national insistence on creative freedom was David Černý’s 1991 “Pink Tank” graffiti art in Prague wherein the artist painted a 1945 Soviet war memorial pink in protest to its associations with the 1968 uprising and longstanding Soviet oppression.

From his vantage point as the provisional President of Czechoslovakia Havel took it all in stride, seeing the symbolism very much in keeping with the same Czechoslovak identity which embraced the Plastic People:

First, most of our people probably share the view that a tank is probably not the best reminder of the sacrifices of the war and they would probably prefer to see some other statue standing there. Second, that young man’s gesture of painting the tank pink probably went down well with our feeling for color, our sense of the theatrical, the ironic, and so forth.

In 1993 Czechoslovakia peacefully split into two states. The creative freedom modeled by the Plastic People of the Universe extended even to the founding of nations.

For more information about World Protest and Reform Movements: Global Perspectives, 1945-1996, please contact Readex Marketing.