The Wall Street Bombing of 1920: Using Historical Newspapers to Trace Terror Campaigns of the Early 20th Century

Lunchtime. Wall Street, September 16, 1920.

Secretaries and clerks crowded the streets of the financial district as a man parked a horse-drawn wagon opposite the headquarters of the J.P. Morgan bank and walked away. The wagon was a bomb: dynamite, with sash weights and other metallic objects serving as makeshift shrapnel. Shortly after noon it exploded.

The blast shredded the wagon, killed the horse and took the lives of 38 people. Hundreds more were injured. Buildings were damaged and broken glass littered the street. The need to get hundreds of victims to hospitals meant that many were delivered not by ambulance, but by cars that were parked nearby. The street was cleaned. Some evidence was surely lost.

On that first afternoon, police weren’t sure whether the bombing was deliberate or the result of a crash between an automobile and a truck delivering explosives to a nearby construction site. Before long, though, members of the bomb squad became convinced it had been a bomb. Once that was determined, police began trying to figure out who had done it.

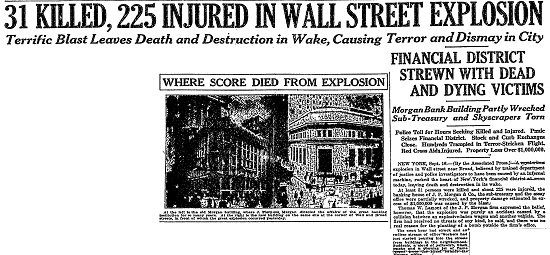

The explosion was big news across the country. Thanks to wire service reports, afternoon papers in the Midwest and West could publish stories about it on the day it happened. The Fort Worth Star-Telegram used the Associated Press story, under the headline “Blast Wrecks J.P. Morgan Offices; Over Score Killed.”

A mysterious explosion, disastrous in its effects, occurred today in Wall Street, killing more than a score of persons and injuring hundreds.

Office workers were just hurrying into the street for their noonday meal when a jet of black smoke and flame rose from the center of the world’s greatest street of finance.

Then came a blast and a moment later scores of men, women and children were lying, blood covered, on the pavement.

Two minutes later nearly all the exchanges had closed. Men had turned from barter to an errand of mercy, and there was need of it.

The Star-Telegram story ran about a column and a half on the front page, with a photo, and a full column on the next page. The next day Montana’s Anaconda Standard had a total of six photos and a map. While its front-page story didn’t take up much space, after the jump there were five-and-a-half columns with more detail. The “jet of black smoke and flame” was now “yellowish, black smoke and a piercing jet of flame.”

Thousands of clerks and stenographers fled in terror from adjoining structures. Scores fainted, fell, and were trampled on in the rush. Meanwhile, the noise of the explosion, which was heard throughout lower Manhattan and across the river in Brooklyn, brought thousands of the curious to the scene….

[Police Commissioner Enright] said certain developments do not uphold the theory that a truckload of dynamite had exploded because his men found slugs of cast iron all around the scene of the disaster. These slugs, he said, resemble the weights of windows, broken in pieces, but they did not come from windows in the vicinity of the explosion…

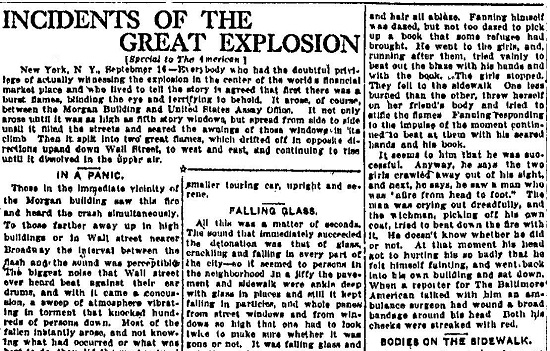

Also on September 17 the Baltimore American provided a great deal of color and atmosphere in its account.

The biggest noise that Wall street ever heard beat against their ear drums, and with it came a concussion, a sweep of atmosphere vibrating in a torrent that knocked hundreds of persons down. Most of the fallen instantly arose, and not knowing what had occurred or what was best to do, they did the most natural thing—they skidaddled in whatever direction seemed to be away from the catastrophe. They ran madly down Broad street, up Nassau street and toward the limits of Wall street in both directions, or else they turned into buildings and sought safety within walls….

The sound that immediately succeeded the detonation was that of glass, crackling and falling in every part of the city—so it seemed to persons in the neighborhood. In a jiffy the pavement and sidewalk were ankle deep with glass in places and still it kept falling in particles, and whole panes from street windows and from windows so high that one had to look twice to be sure whether it was gone or not. It was falling glass and not the explosion itself that killed most of those who were in the list of fatalities.

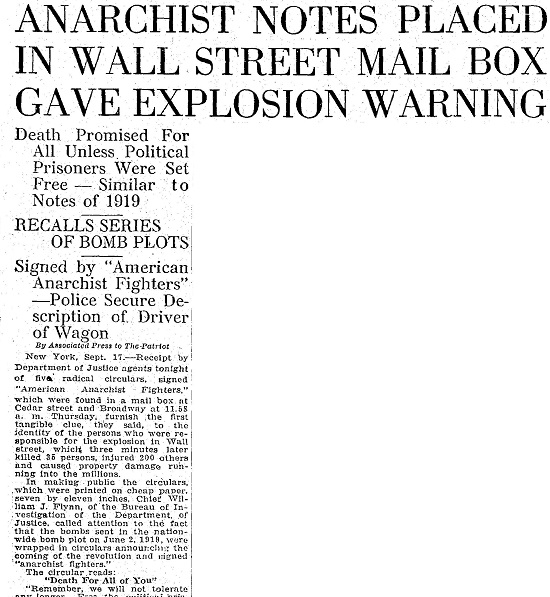

As the police investigation continued, a handful of circulars were found in a nearby mailbox. They were brief and signed by a group name, rather than by an individual. Some had misspellings. Based on this evidence, the Patriot of Harrisburg, Penn., headlined its story “Anarchist Notes Placed in Wall Street Mailbox Gave Explosion Warning.” A subhead read “Death Promised for All Unless Political Prisoners Were Set Free—Similar to Notes of 1919—Recalls Series of Bomb Plots.” According to this article, the circular in full read:

Death for All of You

Remember, we will not tolerate anymore. Free the political prisoners or it will be sure death for all of you.

American Anarchist Fighters

The article also quoted an eyewitness, Lawrence Serbin, who had been selling chocolates to the crowd on Wall Street. It described the wagon and driver.

The wagon was a bum work wagon with dark dirty red paint, something like a dirt wagon and about twice the size of those used by street cleaners. It was a rusty red color and was drawn by an old brown horse.

The driver was a dark complexioned unshaven wiry man, probably 35 or 40 years old, and dressed in working clothes and a dark cap. He seemed to be about five feet six inches tall. He had dark hair.

Still, the reporting left several questions: Who were these so-called political prisoners? Who could free them? And what were the “Notes of 1919”?

The year 1919 had seen two significant bombings that would have been fresh in readers’ minds. The first was a letter bomb campaign. In April, packages purporting to contain a sample from Gimbel Brothers department store were sent to many prominent American politicians and businessmen. They actually contained a stick of dynamite, with some mercury blasting detonators and a small bottle of acid. The acid would set off the detonators, which in turn would cause the dynamite to blow up.

Yet because it’s unlikely that any of the men on the list opened their own mail, only the maid and wife of former Georgia Senator Thomas W. Hardwick suffered injuries. Hardwick had authored the Immigration Act 1918 which barred anarchists from entering the U.S. His wife suffered burns and cuts on her face. The maid lost her hands.

Then on June 2 bombs went off in eight cities at nearly the same time. Like the Wall Street bomb, these had metal bits added to create shrapnel. The bomb outside the house of Attorney General A. Mitchell Palmer went off a bit early, blowing up the bomber. Palmer and his family were at the rear of his home, shaken but still alive. The front of the house was ruined. Across the street was the home of Franklin Delano Roosevelt and his wife Eleanor. Pieces of the bomber ended up on their lawn.

These bombs, like the Wall Street bombing, were accompanied by a document entitled “Plain Words.”

Do not say we are acting cowardly because we keep hiding, do not say it is abominable; it is war, class war, and you were the first to wage it under cover of the powerful institutions you call order, in the darkness of your laws, behind the guns of your bone-headed slave….

We are not many, perhaps more than you dream of, though but are all determined to fight to the last, till a man remains buried in your Bastilles, till a hostage of the working class is left to the tortures of your police system, and will never rest until your fall is complete, and the laboring masses have taken possession of all that rightly belongs to them.

There will be bloodshed; we will not dodge; there will have to be murder: we will kill, because it is necessary; there will have to be destruction; we will destroy to rid the world of your tyrannical institutions.

It was signed by The Anarchist Fighters. Like the letter bomb campaign from earlier in the year, none of the intended victims were hurt, let alone killed. A watchman in New York City died, as did the Washington bomber.

Michigan’s Kalamazoo Gazette on June 4, 1919, published an article headlined “Bombs Are Anarchists’ Propaganda of the Deed.” The subtitle read “Murder Anarchism of Today Grew Out of Bakunin’s Assassination Doctrine.” It tells the story of the terrorism in Europe in the late 19th century and the bombs in the U.S. before and after World War I, but is most notable for its stereotypic image of an anarchist bomb thrower.

That dead bomber was thought to be a man named Carlo Valdinoci. After war was declared in 1917, the anarchist newspaper Coanaca Suovvervsiva (The Subversive Chronicle) published an article urging Italian anarchists to remove themselves from the country, to avoid being drafted. Paul Avrich, in his work Sacco and Vanzetti: The Anarchist Connection, says that Valdinoci made his way to Monterrey, Mexico, where he lived communally with other anarchists, including one called Mario Buda. Avrich believes that in Mexico the men formed an action group within the larger anarchist movement. He traces their return to the U.S. and the plots that accompanied them.

After the Wall Street bombing, suspicions soon turned to these Italian anarchists. Two, Nicola Sacco and Bartolomeo Vanzetti, had been arrested for murder earlier in the summer. And many such anarchists were subscribers to the Coanaca Suovvervsiva, edited by Luigi Galleani, a charismatic man and powerful writer who had spent years in exile from Italy, living in France and Egypt before arriving in the U.S. His paper was notable not only for its radical content, but also for the fact he advertised in its pages a pamphlet called La Salute e in voi! (Health is in you!)—a set of instructions for making bombs.

So back to the question of political prisoners. Like many anarchists, the Italian-American variety believed, as Pierre-Joseph Proudhon put it, that Property is Theft. There should be no monarchy, no aristocracy—indeed, no government. For, as Proudhon wrote in his The General Idea of the Revolution in the Nineteenth Century:

To be GOVERNED is to be watched, inspected, spied upon, directed, law-driven, numbered, regulated, enrolled, indoctrinated, preached at, controlled, checked, estimated, valued, censured, commanded, by creatures who have neither the right nor the wisdom nor the virtue to do so. To be GOVERNED is to be at every operation, at every transaction noted, registered, counted, taxed, stamped, measured, numbered, assessed, licensed, authorized, admonished, prevented, forbidden, reformed, corrected, punished. It is, under pretext of public utility, and in the name of the general interest, to be place[d] under contribution, drilled, fleeced, exploited, monopolized, extorted from, squeezed, hoaxed, robbed; then, at the slightest resistance, the first word of complaint, to be repressed, fined, vilified, harassed, hunted down, abused, clubbed, disarmed, bound, choked, imprisoned, judged, condemned, shot, deported, sacrificed, sold, betrayed; and to crown all, mocked, ridiculed, derided, outraged, dishonored. That is government; that is its justice; that is its morality.

(translated from the French by John Beverly Robinson, 1923)

Or as Beverly Gage wrote in her book, The Day Wall Street Exploded: A Story of America in Its First Age of Terror (pages 44-45):

Among anarchism's founding premises was the idea that capitalist society was a place of constant violence: every law, every church, every paycheck was based on force. In such a world, to do nothing, to stand idly by while millions suffered, was itself to commit an act of violence.

Gage made it plain that Italian anarchists were the primary suspects for the Wall Street bombing. Galleani had been deported back to Italy in 1919, hindering the investigation. Buda is thought by Avrich to have been the Wall Street bomber. He left the country after the bomb went off.

One remarkable thing about the campaign of terror from the Italian anarchists is that the main targets were so often missed. Another is its persistence. A third is how few arrests were made.

As U.S. government administrations changed, the new head of the Bureau of Investigation changed the direction of the Wall Street bombing investigation. He believed that Communists were responsible and sent investigators to Eastern Europe. Time passed. Wall Street chose not to remember the bombing on its anniversaries.

William J. Flynn, former head of the Bureau of Investigation and former Chief of the United States Secret Service wrote about his famous cases in 1922. The bombing was one of them. The Tampa Sunday Tribune published this installment on March 5th under the headline “On the Trail of the Anarchist Band—Chief Flynn.” This excerpt explains why Flynn didn’t make any arrests:

Galleani, for instance, will suggest. One of his close companions will pass on the suggestion. The idea will pass hither and yon until eventually a particularly wild man or woman will touch off the bomb or ignite the fire. Trace it back and you become lost in the most complicated labyrinth of indirect statements, evasions and plain lies, and you learn sooner or later that you are destined to emerge from the maze at the same spot you entered, having gained nothing.

As the Twenties went on, violent acts of protest against social conditions became rare. Sacco and Vanzetti even became a cause celebre. They were convicted, sentenced to death, appealed, and lost their appeals. People became convinced that their trial had been tainted by the attitudes of the judge. Protests were held around the world. As the time of their execution approached, one of them urged his comrades to avenge them, but to no avail: the men were executed by electric chair in 1927.

For more information about Early American Newspapers by Series, please contact Readex Marketing.