Why de dickens?: The Lampooning of African Americans as an American Form of Entertainment

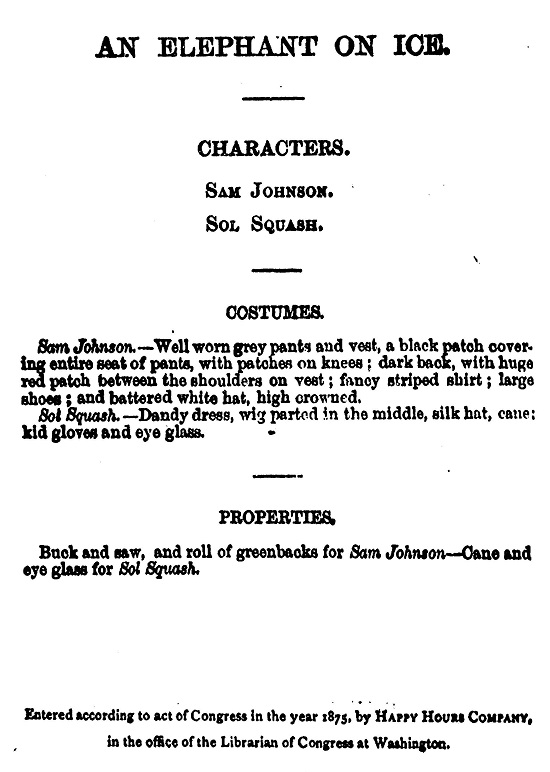

Included in the second release of Nineteenth-Century American Drama: Popular Culture and Entertainment, 1820-1900, are several minstrel plays. Developed in the United States beginning in the 1830s, minstrel shows mocked the appearances and language of black characters, reinforcing white views on race for more than a century. This first example, An Elephant on Ice, is subtitled "An Ethiopian Interlude, in One Scene":

Costumes

Sam Johnson.—Well worn grey pants and vest, a black patch covering entire seat of pants, with patches on knees; dark back, with huge red patch between the shoulders on vest; fancy striped shirt; large shoes; and battered white hat, high crowned.

Sol Squash.—Dandy dress, wig parted in the middle, silk hat, cane; kid gloves and eye glass.

An example of the dialogue as the play opens:

Scene.—A street in second or third grooves.

Enter Sam Johnson R., carrying a buck and saw on his shoulder.

Sam J. Well here I am again. Bin up one street and down anudder street and all aroun’ de streets, and couldn’t find a job. Was just t’inkin’ ob jiuin’ de miustrums, or dancin’ for eels, or gitting sent up, or sumfin, when I stumbled over some o’stacle, and if dar wasn’t dis big roll of bank bills.

(Fishes out a big roll of greenbacks from his breeches pocket.)

(Enter Sol Squash L.)

Sam. ‘Mornin’ Sol. All nature seems gay dis mornin’. Missus Squash and all de little Squashes well dis mornin’?

Sol. (Quizzing with eye-glass.) Who dat talkin’ so free? Neber been in perlite society befo’? Folks puts a handle to gemmen’s names.

Sam. What for you puff up so pompous, Mr. Bullfrog? Forget you was once a polywog. Guess somebody must been fool ‘nuff to leave you a pos’crip or somefin’.

Sol. What dat to you? I ain’t no common darkey, I guess—no sawbuck niggah no bleached cottons, nudder.

Sam. Mighty fine—mighty big for de cook ob de Alabaster house. Big as de hotel you gets your libbin’ by. Elephant on de ice, p’r’aps you t’ink you’self. You got de fine clothes, but I got de greenbacks, and it’s dem dat makes de fine birds. (Shows roll.) Dat’s a bigger roll dan you had for breakfas’ dis mornin’.

The two characters indulge in some further badinage leading to a metaphorical rug being pulled from under the other. Sam, having promised Sol a treat of oysters when asked about the offer by Sol, replies

Sam. O, I don’t want none—can’t eat de dam t’ings. Good-bye, Sol!

After the Civil War there arose a lot of prose humor written in what was presented as black dialect which was derisive and exaggerated. The brevity of the play indicates it was intended as a segment of larger revues. The next imprint is similar.

Intended to run for twenty minutes, The Black Bachelor: Negro Farce in One Act was published in 1898 and has four characters, chief among them Isaacs who is described as “a fat and white-haired old Bachelor.” Timothy is his comic man-servant. The dialect is similar to the previous play. At the outset, Isaacs is calling for his newspaper.

A sample of its dialogue:

Isa. Now, why de dickens isn’t dat paper here before dis time in the morning?

Tim. De cook asked me to lent it to her, cos she wanted to look in de agony column, and it quite slipped my memory.

Isa. What slipped your memory? De cook, de paper, or de agony column?

Tim. All ob dem. Sah.

It continues:

Isa. [referring to Timothy] Dat’s about de stupidest [derogatory word] I eber come across; tank goodness I’m not married! I don’t know howeber I’d get along if I had a wife, specially one like de last cook.

In essence, the play is a series of minor calamities perpetuated by the hapless Timothy. As dimwitted as Timothy seems, Isaacs is not a great deal sharper. It would seem the intent is to mock all the black characters and any of their assumptions or pretenses.

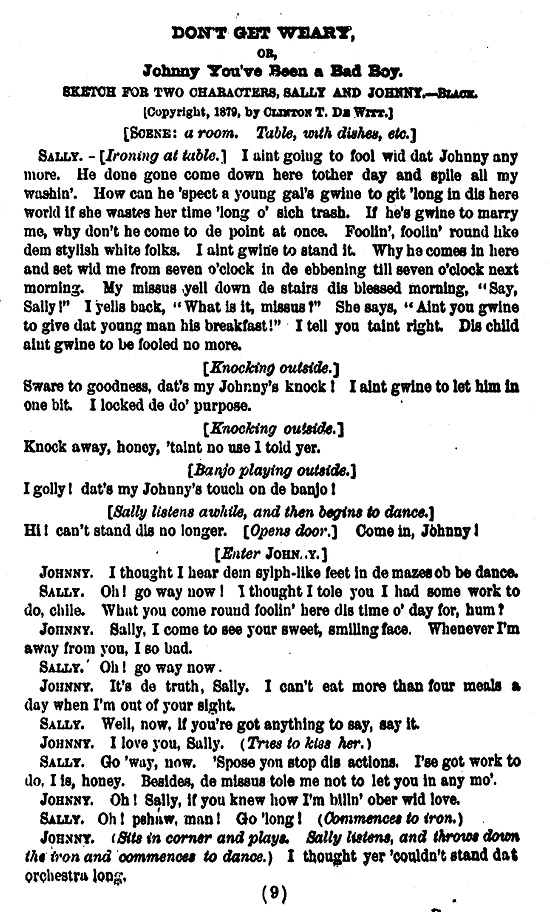

Another short play, this one titled Don’t Get Weary Or, Johnny, You’ve Been a Bad Boy, is described as a "Musical Sketch In One Act". Called a “Darkey & Comic Drama" by its publisher, the script states that its playing time is fifteen minutes. The costumes are given as “Characteristic Negro Rig.” There are two characters, Johnny and Sally. Again, the dialect is meant to deride.

Sally.—(Ironing at table.) I ain’t going to fool wid at Johnny any more. He done come down here tother day and spile all my washin’. How can he ‘spect a young gal’s gwine to git ‘long in dis here world if she wastes her time ‘long o’ sich trash. If he’s gwine to marry me, why don’t he come to de point at once.

The playwright uses “gwine’ for “going” twice, but in the first sentence he uses ‘going.” It seems a careless inconsistency, but it is in keeping with the varied attempts to portray the dialect which is not genuine.

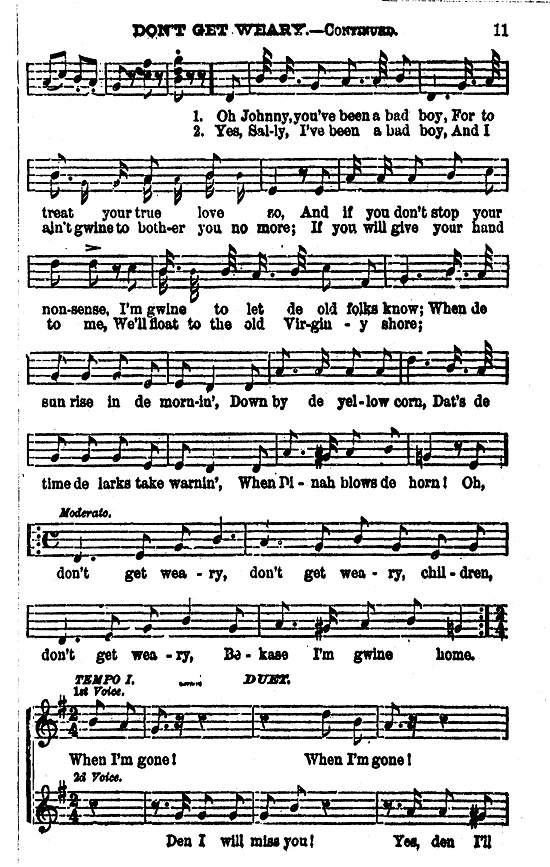

Johnny appears and begins to woo Sally, declaring “I can’t eat more than four meals a day when I’m out of your sight.” She demurs and returns to her ironing, but Johnny begins to play his banjo, and soon she begins to dance. When she hears mistress calling to her she becomes worried, urges Johnny to hide, and grabs up her iron again. Sally and Johnny argue, but Johnny coaxes Sally into joining him in singing “dat song we used to sing down on de ole plantation.”

Sally. Well, now I tole yer, just dis once, honey, and dat is de last. [Symphony of song is played. Sally sings the first verse, and Johnny the 2d. Dance, and Curtain.]

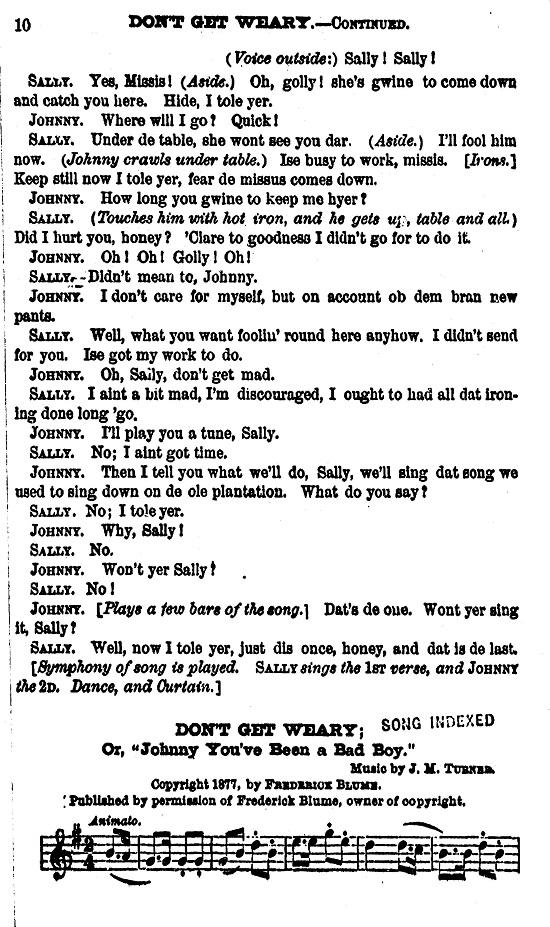

The song is “Don’t Get Weary” with the credit for the music ascribed to J.M. Turner and the copyright in 1877 to Frederick Blume. As promised, it’s over quickly.

For more information about Nineteenth-Century American Drama, please contact Readex Marketing.