The Flash Press: New York’s Early 19th-Century “Sporting” Underworld as a Unique Source of Slang

Green’s Dictionary of Slang, launched in print in 2010 and available online since 2016, currently offers some 55,400 entries, in which are nested around 135,000 discrete words and phrases, underpinned by over 655,000 examples of use, known as citations. Thanks to the online environment, it has been possible to offer a regular quarterly update to the dictionary.

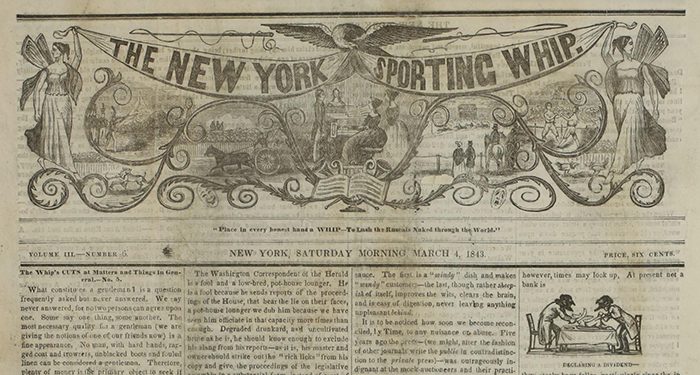

During the summer of 2020, I focused primarily on American Underworld: The Flash Press, a newspaper collection of the American Antiquarian Society and digitized by Readex. Its 45 titles (ranging from a single edition to runs covering multiple years) provided more than two-thirds of additions and changes in last August’s update. In this article, a version of which appeared on my own blog, I write about the nature of the “flash press” and some of the slang terms that have been extracted from it.

Here’s this morning’s New York Sewer! Here’s this morning’s New York Stabber! Here’s the New York Family Spy! Here’s the New York Private Listener! Here’s the New York Peeper! Here’s the New York Plunderer! Here’s the New York Keyhole Reporter! Here’s the New York Rowdy Journal

— Dickens, Martin Chuzzlewit (1844)

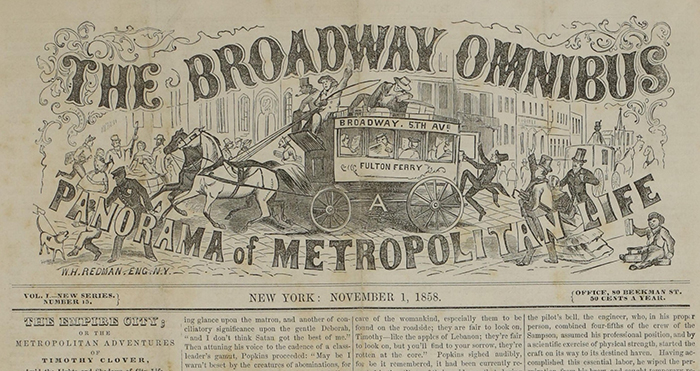

Taking his first steps through 1840s New York City, the young hero of Dickens’ Martin Chuzzlewit pays a visit to the offices of the New York Rowdy Journal. The paper was Dickens’ creation, a nod to what he saw as the trashy standards of the contemporary New York press, but there were examples to draw on, sufficient to be known collectively as the “flash press.” Flash, that is, as in hedonistic, immoral, sexually sophisticated and as a result of all this, short-lived.

In the accompanying illustration by “Phiz” one may see lying on a cupboard, alongside bottles marked respectively “ink” and “poison,” a volume marked “slang dic.,” but if there was a slang dictionary in use, then it must have been Pierce Egan’s revision of Grose or “Jon Bee’s” Dictionary of the Turf, the Ring, the Chase, the Pit, &c., both published in 1823 and both, of course, British. America would not have a homegrown version for a further 15 years.

Its potential contents, however, were ready and waiting.

Thirty years on, writing in his Americanisms (1872) Maximilian Schele de Vere stressed that

the most fertile source of cant and slang, however, is, beyond doubt, the low-toned newspaper, written for the masses, which, instead, of being a monitor and an instrument of improvement in the hands of great men, has become a flatterer of the populace, and a panderer to their lowest vices.

Thirty years later still, James Murray of the Oxford English Dictionary (OED) acknowledged the pre-eminence of the popular press in keeping lexicographers abreast of language’s cutting edge. Neither mentioned, but both might well have done, the “flash press.” It ticked their every box.

The flash press flourished for a decade or so. Although in the case of certain titles frustratingly few individual issues have survived, there remain a good number of papers that can be consulted, thanks to the American Antiquarian Society and the digitized versions created by Readex and available as American Underworld: The Flash Press, Among them are The Whip, The Flash, Ely’s Hawk & Buzzard, The Subterranean, The Flagellator, The Scorpion, The Libertine, Life in Boston and New York (from Boston, Mass.), The Spy (from Manchester, N.H.), Venus’ Miscellany (inching towards modern pornography) and various copycats and clones. They were very much a Yankee creation and focused on a local audience. Other “sporting” journals” (best known being The Spirit of the Times, its most successful editor being an ex-“flash press” hack, George Wilkes, formerly of The Flash) might embrace a wider America, or even if based in New York, such as the National Police Gazette, draw in readers from across the country. The hardcore did not, nor did they wish to.

They were mainly, but not uniquely American. The 1840s saw equivalents in London (Paul Pry and Sam Sly, or The Town) and Sydney, Australia (The Satirist and Sporting Chronicle) but like their New York equivalents, they vanished almost as soon as they had started picking up readers. The consumers may have enjoyed their salacious prurience; those with the power to curb it and those who found themselves its targets (sometimes one and the same) did not.

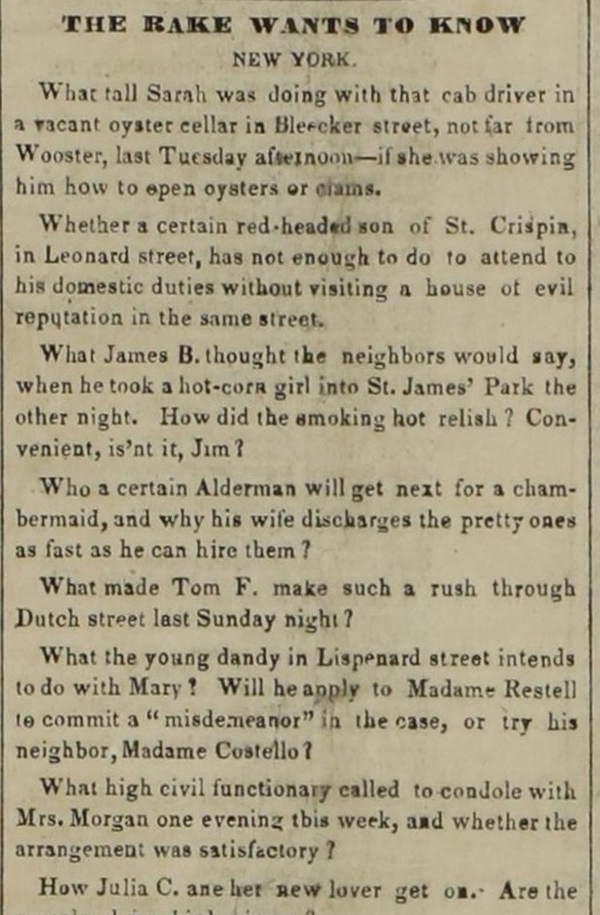

These newspapers were based on gossip, typically indicated with a wealth of initials which, were “reform” (i.e., a cash payment) not made soon, would be filled out with a full name. In Dickens’ case, his 1842 trip to Gotham was noted by hints at a visit to a brothel that does not, unsurprisingly, appear in his own American Notes. As the Whip of April 23 put it “There was a little dog, and he had a little tail, Oh, what a living Boz you is.” And we can almost surely assume that “tail” here took on its slang meaning: the penis. (It is also fascinating to witness how quickly Dickens creations entered common usage, almost before a new serial had been finished.) The press posed as enthusiasts of reform, but it was the same enthusiasm that has underpinned the hypocritical mouthings of generations of tabloids. The supposedly wicked were shamed, all the better to publicize the details (or at least the heavy-handed suggestions) of their sins. A column like The Rake’s “Invisible Spy” offered all the smug spitefulness of the most dedicated and moralizing censor. Blackmail was never far away.

The columns, usually headed “The X [the journal’s title or alternatively a town or city’s name] Wants to Know,” played on the journal’s name to threaten “whipping,” “spying,” “flagellation,” and the clawed descent of both “hawks,” “buzzards,” and other birds of prey. It was these columns, of course, skating on the thinnest of ice, that would see these newspapers prosecuted and shut down. Fifty years later the tradition persisted. Columns headed “They Say” in such Australian papers as the Sunday Times (from Perth, Western Australia) sailed equally close to the wind, as they retailed the scabrous suggestions of what it was that “they” allegedly were saying. And if anything Australia’s racist stereotyping, bad enough in mid-century America, was even worse.

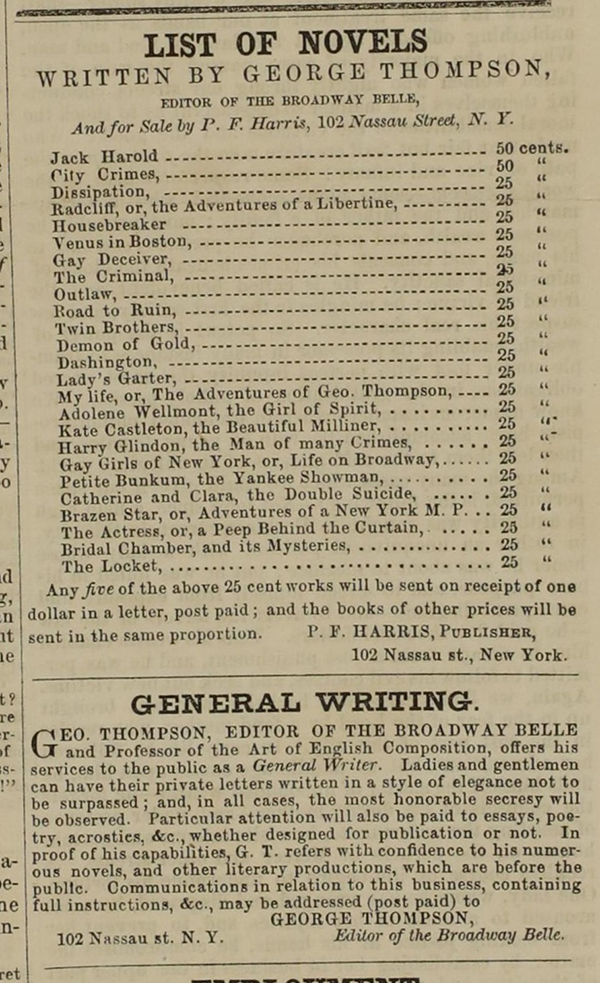

It was not all gossip. There was “racy” fiction too. Foremost among its contributors was George Thompson, who also edited on occasion. His many stories mixed thinly veiled pornography (with constant references to nymphomania, pedophilia, incest, gay sex, miscegenation and group sex), true-crime stories and a fascination with the bizarre. They were regularly advertised in the press: most priced at a quarter per book and five for a buck:

At times the flash press became positively mainstream. There would be regular descriptions of brothel dances, with every “inmate’s” (i.e. prostitute’s) dress as minutely delineated as a legitimate magazine might lay out those paraded by princesses at a royal wedding. Like London’s 18th-century guides to the pleasures of Covent Garden, “houses” were specified, along with their address, the name and reputation of “Madame,” the qualifications and charms of the inmates, and the decorations, both down- and upstairs, that clients might expect to encounter. Some journals offered pictures, of girls and of their luxurious backdrop. There were lists of drinks that one “nymph” or another preferred to imbibe. There were also instructions as to the best theaters to visit if you wanted to find a partner for the night: the “third tier” circle of the Chatham or the Chestnutt were especially recommended. If all else failed, there were regular mentions of Mrs. Restell, New York’s best-known abortionist and allegedly protected—for a cut—by the city’s Police Commissioner Matsell. The papers, like their “straight” peers, had no mutual affection. It was a rare issue which did not feature one savaging the other—usually on the grounds of the supposedly lax morality of their editors. The Whip and The Rake were especially barbed towards each other, reflecting, perhaps, their success and the near-identical nature of their writing.

For a detailed history of the flash papers, well illustrated by a range of excerpts, the best resource is The Flash Press: Sporting Male Weeklies in 1840s New York (2008) by Patricia Cline Cohen, Timothy J. Gilfoyle, and Helen Lefkowitz Horowitz. This looks at the sociology and when relevant the politics behind the press; at those who edited them and those who read them; and those, mainly existing within the New York sexual underworld of brothels, pimps, bawds, whores and of course clients, who provided—either as informers or participants—their stories.

Patricia Cohen and her colleagues only mention the language of the press in passing, focusing on what it said rather than the actual words and phrases that comprised it. My own researches, reading through a large proportion of the titles available, have, as is slang’s way, ignored the social backdrop, and gone for the vocabulary.

Given a source that has proved so remarkable in the fecundity of material, one word leaps out, though it has no claims on slang: serendipity, or what Shakespeare’s villainous tinker Autolycus termed the snapping up of unconsidered trifles. Not in the research, which requires serious concentration, but in what it displays: the press offers up approximately 250 hitherto unrecorded terms; in addition, and indulging the “historical” lexicographer’s holy grail: the “first recorded use,” there are around 375 predates. But had these papers not survived—and given their lurid content most readers preferred not to start a collection—and then been made available to scholars, this information would have remained unknown and unexhumed. This, of course, is true of all research: if you don’t know it’s there, how can you interrogate it. That this small but revelatory collection has survived and is now available for excavation only underlines its value.

For the slang scholar, lexicographer or otherwise, this has a larger importance. The received wisdom has often been that American slang—which still effectively meant that created in New York City—had yet to come fully into use before mid-century. The discoveries made available in the columns of the “flash press” make it wholly clear that this was not the case. Homegrown American slang was up and running from at least the 1830s.

Twenty years later George Matsell’s Vocabulum, or The Rogue’s Lexicon, the country’s first native dictionary of slang, proved the point. To what extent he read the flash press is unknown; as New York’s police chief he certainly gained regular mentions (177 appearances between 1841 and 1871).

As a lexicographer Matsell did his own digging. As he explained in the dictionary, much was via face-to-face conversations; too little was as yet written down. To look only at the letter “B”—for which Vocabulum lists some 127 headwords—one finds the following 39 terms (nearly one third) that for which, when Matsell published, his is the first recorded use: badger (a thief who rifles the pockets of a man who is currently engaged with his accomplice, a prostitute), badger-crib (a brothel wherein one is robbed), barney (a fake fight, arranged by criminals to distract a potential victim’s attention), beat (to rob), beaters (boots), bet one’s eyes (to watch a game but not get involved in the betting), big thing (a large amount of plunder), bingo-boy (a drunkard), bit (arrested), blarney (a picklock), take a blinder (to die), blink (to go to sleep), bludget (a female thief), boarding house (a prison), boat (to transport a convict), boat with (to become partners with), boated (sentenced to a long term in prison), body cover (an overcoat), boke / boko (the nose), booby-hatch (a police station), boshing ( a whipping), bots (boots), bracket-mug (an ugly face), break o’day drum (an all-night tavern), break a leg (to seduce), broad-pitching (“three-card monte”), brother (of the) bolus (a doctor), brother of the surplice (a priest), brush (to “soften up” a victim), buck (an unlicensed cab-driver), bugger (a pickpocket), bully (a cosh), bummer (a scavenger), bumy-juice (beer), burned out (exhausted), burner (a card-sharp), burst (a spree), burster (a burglar), butteker and butter-ken (a shop), buttered (whipped), and button (to act as a confidence trickster’s accomplice).

But Matsell’s list could have been even larger. The lexis offered in the flash press, which he seems to have bypassed, coincides barely if at all. (Perhaps he was unwilling to revisit a medium that could be so hostile when covering his own exploits). Both Matsell and at least one paper use burst (a spree, an indulgent party). There is badger, but as a verb, referring to the act of the girl in conning the client, and badger game, which Matsell ignores. For him boarding house is defined as a prison (he has the synonym boarding school), while the press opts for a brothel, with its attendant boarders and boarding ladies; it also regularly uses board, to live as a brothel prostitute. Matsell has a couple of brothers: of the bolus (a doctor) and of the surplice (a priest) but not the press’s preference, of the brush (a painter). Both offer bummer, but the press defines him as “a fast young man,” while Matsell has a scrounger (a weak form of the earlier looter).

None of which is to invalidate the police chief. If one accepts the late 19th century report of the writer William Cumming Wilde, both criminals and policemen backed up the Vocabulum’s lexis. Wilde cited the book both to “one of the most desperate characters that our city has produced” and to “one of the best as well as oldest detectives in our country […] a man who has followed his profession for fully half a century.” Both supported the accuracy of Matsell’s lists. And “subsequent interviews with some of the best officers on our police force fully confirmed this.” Still, one wonders what else there was, noticed by neither source. Nor, however, does it go to prove slang’s oft-suggested ephemerality. These uses by the press may be the first, but they are by no means the last. Serendip again: no one lexicographer, even with a copper’s facilities, can collect everything; nor can a down-market hack, however well wired into his subject-matter, glean a whole lexis.

Both the slang neologisms and the pre-dating of existing terms are worth mention. If the topics seem somewhat monocular, thus the papers that reported on them. Of the newly discovered flash press terms, a small selection offers:

- land frigate (a prostitute)

- sashay (to have sexual intercourse)

- zoe (a prostitute)

- gravy-eyed (insult offered a woman)

- carry the war into Africa (to take things further)

- give someone a striped jacket (to give a beating)

- grinding mill (a brothel)

- gum game (a confidence trick, though it depends not on speech, as “gum” might suggest, but the activity of the opossum, which, in its efforts to elude the hunter, climbs to the very top of a gum tree, thus taking itself beyond the hunter’s reach and, since it was hunted at night, beyond his eyesight)

- nine months fever (pregnancy)

- stargazer (a womanizer, a prostitute’s client)

- twig the heel (to seduce)

- blow-breeches (a braggart,; a verbose talker)

- horizontal academy (a brothel)

- codfishopolitan (a native of Boston, Mass., from the city’s prime product)

- prop-room (a venue specializing in the “thimble-rig”)

- bell-teazer (a hat, with a curved brim and crown)

- r.g. crib (a down-market tavern, selling rot-gut)

- work on mattresses (to work as a prostitute)

- mumble-peg game (sexual intercourse)

- gin depot/fountain (a tavern).

Then there are the flash press phrases:

- too much pork for a shilling (too much of a good thing)

- look marrowbones and cleavers (to stare aggressively)

- walk up to the ringbolt (to be hanged)

- go in for lemons (to commit oneself wholeheartedly)

- too much pumpkins (something or someone seen as excessive)

- not see one’s own gate an inch from one’s nose (to be “blind” drunk)

- 2:40 on the plank road (the speedy payment of a debt; “2:40” being the time of a fast trotting horse and plank road a play on “plank down,” i.e., money)

- eleven pennies out of the shilling (used to indicate a percentage of non-white parentage and reminiscent of British India’s not sixteen annas to the rupee)

- plus such street-launched catcalls as “how do you live and what do you do in the daytime?” with its inference of addressing a prostitute, and the indefinable “if you don’t look out we’ll get a camel on you!”

As for the predates, and restricting ourselves to the 32 examples that have pushed back slang’s records by 100 years-plus, these are in their way even more interesting. They also are, or were, more examples of the era’s expanding slang vocabulary. (None of these terms—whether “new” or “predates”—are set in stone: any one of them may yet be revealed as even older).

From the longest predate in descending order they are:

- plain sewing (anal intercourse) 171 years predate (1832<-2003)

- grease-pot (an insult suggesting some form of kitchen slavey) 157 years (1848<-2005)

- pigville (the poor end of town, the implication, as usual with pigs, being that the locals are Irish) 156 years (1848<-2004)

- orangutan (a highly derogatory name for an African American) 150 years (1842<-1992)

- speak French (to perform fellatio, the inevitable link of “dirty” French to oral sex) 144 years (1842<-1986)

- burst (to go out on a spree) 142 years (1842<-1984)

- rigging (usually clothes, but here the genitals) 140 years (1848<-1988)

- grindstone (the vagina) 138 years (1842<-1980)

- miff (to get angry) 144 years (1812<-1956)

- sheisty (underhand, unethical) 138 years (1855<-1993)

- get the sack (to have one’s relationship ended) 136 years (1833<-1969)

- hard boy (a thug) 134 years (1851<-1985)

- sack (to end a relationship) 133 years (1856<-1989)

- dragon (an old prostitute) 125 years (1859<-1984)

- horn (a womanizer) 124 years (1843<-1967)

- whistle (the penis) 122 years (1843<-1965)

- bedhouse (a brothel) 118 years (1842<-1960)

- snork (a young man) 118 years (1848<-1966)

- banger (one who hits hard) 117 years (1842<-1959)

- dirty leg (a promiscuous female) 117 years (1861<-1968)

- cut (circumcised) 116 years (1856<-1972)

- horizontal (used in compounds to mean sexual intercourse, here mesmerism and amusement) 115 years (1844<-1959)

- chant (to talk persuasively) 114 years (1842<-1956)

- jug (a figurative sense of Standard English juggle, to fool, deceive) 113 years (1855<-1968)

- fast (sexy, provocative) 112 years (1848<-1960)

- eat dried apples (to become pregnant) 111 years (1854<-1965)

- pork (to have sexual intercourse) 111 years (1856<-1967)

- crawl (a promenade along the street) 111 years (1882<-1993)

- peeps (people) 109 years (1833<-1942)

- ointment (money) 107 years (1842<-1949)

- on ice (to the limit) 107 years (1861<-1958)

- wet deck (a woman or prostitute who performs serial sex acts with a succession of males) 106 years (1843<-1949)

- shag (a person) 103 years 1843<-1946).

Perhaps the most intriguing is that for phat, the usual etymology of which is a deliberately skewed spelling of the positive slang term fat adj. sense 1, but which is also popularly linked to a variety of suggested abbreviations or acronyms, e.g., physically attractive or pretty hips and thighs, etc. All of these link to sense 1, used to describe an attractive woman. Gelded of any sexuality, phat sense 2 is a term of general approval. It is here that one might place another example from the flash press: as published by New York’s Flash on 14 August 1842, “As it is not a very ‘phat’ job to beat oneself […] he elevated his sparkling orbs in search of a victim.” Like slang’s fat, adj. (2), the term means substantial, wealthy and in terms of the con-trick noted here, remunerative. On 14 January 1843 the Albany Microscope gave the term a slight tweak: “It contained a lot of good copy, selected with an eye to phat takes—plenty of sorts to work with, and a competent ‘set of hands’ to either distribute or to set up.” The sense is again “remunerative,” but in terms of figurative rather than literal reward. The skewed spelling must be attributed to both authors’ personal peccadillo. It would take a further 120 years for it to reappear.