"Forever Bear In Mind:" Spreading the News of Lexington and Concord

Important figures in the distribution of information in Colonial America were the post riders who carried both mail and printed materials. Because many postmasters were also printers, they relied heavily on these horseback-riding carriers to deliver the mail as well as the labors of their presses.

The efforts of post riders often intersected with those of two other groups: expresses, who were couriers engaged to deliver urgent materials to another party as fast as possible, and the various committees of correspondence, the organized groups set up by local governments to exchange intelligence and defend colonial rights. Together, they created a vast information network within and between the thirteen American colonies. By using the Archive of Americana to examine the work of one Colonial postmaster and printer, we can see how this intricate web of communication extended from publisher to publisher.

Isaiah Thomas (1749-1831) often employed his post riders in the cause of American liberty. In his History of Printing, Thomas described how shortly after he removed his famous printing press—"Old Number One"—from Boston to Worcester in April 1775, "he was concerned, with others, in giving the alarm" about the Royal troop movement on Lexington and Concord during the night of April 18th. 1

In addition to carrying copies of his newspaper—the Massachusetts Spy—to subscribers, Thomas's post riders also carried the paper to other printers who, in turn, shared their papers with Thomas. This system of "exchange papers" between printers was a chief method by which Colonial printer-publishers gathered and shared news. It was a common practice for printers to reprint any information they desired from any other source. Sometimes they attributed the source, but often as not they simply began their accounts with the words "we hear"—assuming that their readers were less interested in the source than in the information itself. Colonial printers also gathered their news from ship-bound English and European newspapers, personal correspondence, official governmental reports and publications and word of mouth.2

The first printed newspaper account of the initial violence of the American Revolution appeared in the Boston News-letter, the oldest colonial newspaper. However, the April 20, 1775 Newsletter account of the Battles at Lexington and Concord could not be more different than that which later appeared in Thomas' May 3, 1775 Spy. The Newsletter's loyalist sympathies permitted only one paragraph, which briefly surmises the events of the day. It does pay passing mention to Thomas and the others who spread the alarm, stating that "Upon the People's having Notice of this Movement on Tuesday Night, alarm Guns were fired throughout the Country, and Expresses sent off to the different towns..." This account concludes with a clear statement of the confusion that swept across the Bay Colony in the days following the conflict: "The Reports concerning this unhappy Affair, and the causes that concurred to bring on an Engagement, are so various that we are not able to collect any Thing confident or regular, and cannot therefore with certainty give our Readers any further Account of this shocking Introduction to all the Miseries of a Civil War." 3

Over the next six weeks of 1775, 27 colonial newspapers would break the news of the Battles of Lexington and Concord. The most substantial reports appeared in the Salem Gazette on April 21 and later reprinted in the Essex Gazette on April 25, the Essex Journal on April 26 and the Spy on May 3.

Thomas' account in the Spy is perhaps the most important because of his own participation in the event. As he himself described on April 19th, "he crossed over to Charlestown, went to Lexington, and joined the provincial militia in opposing the King's troops."4 Because Thomas was clearly on the field of battle, Frank Luther Mott, the great historian of journalism, has credited him with being America's first war correspondent.5

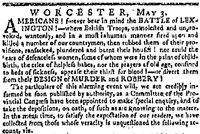

Most Colonial newspapers placed their local and regional news on the second and third pages, and thus on page three of the May 3rd Spy Thomas wrote: "Americans! forever bear in mind the BATTLE of LEXINGTON! where British Troops, unmolested and unprovoked wantonly, and in a most inhuman manner fired upon and killed a number of our countrymen, then robbed them of their provisions, ransacked, plundered and burnt their houses! nor could the tears of defenseless women, some of whom were in the pains of childbirth, the cries of helpless babes, nor the prayers of old age, confined to beds of sickness, appease their thirst for blood! - or divert them from the DESIGN of MURDER and ROBBERY!" 6

This, the first piece ever printed in the community of Worcester, Massachusetts, appeared in the first Colonial newspaper designed specifically for the "middling" classes. The Spy was enormously popular; while most Colonial newspapers had circulations of 400 to 1,000, the Spy boasted 3,500 subscribers from throughout the American Colonies.

As the breathless tone of shock and outrage in Thomas's description attests, his aim was to unite all the colonies behind the actions of the Minutemen of Massachusetts. Above the masthead of this issue are the words: "Americans!---Liberty or Death!---Join or Die!"

Thomas's delay in issuing the Spy was due to a lack of paper. The April 29, 1775 journal of the Committee of Safety of the Province stated "Letters from Col. Hancock now at Worcester were read, whereupon voted that four reams of paper be immediately ordered to Worcester for use of Mr. Thomas, Printer, he to be accountable".7 When that shipment of paper finally arrived in Worcester, Thomas resumed publication of his paper, printing his account of the Battle.

Thomas's opening impassioned plea is also unique. As his post riders spread copies of the Spy to subscribers and other newspapers, we see further evidence of Thomas' influence in the world of Colonial printing. The May 8th issue of the Connecticut Courant reprinted Thomas's entire account, as did the May 10th issue of the Connecticut Journal. Additionally, the Norwich Packet and the Connecticut, Massachusetts, New Hampshire and Rhode Island Weekly Advertiser listed the dead as they appeared in Thomas's May 3rd Spy. The reference to a Worcester dateline in both accounts is further evidence that they used Thomas's version of the event, despite the fact that these papers offered no attribution.

While slow by our modern standards of communication, hand-operated printing presses linked by galloping dispatchers provided a remarkably fast and effective system of communication. In 1775, this system carried word to all thirteen colonies of the violent breach with England that would eventually form a new nation and a new world order.

Footnotes

1 Thomas, Isaiah The History of Printing in America with a Biography of Printers, and an Account of Newspapers, Worcester, Mass, Isaiah Thomas, Jr., 1810, p. 384

2 For an analysis of the kind of news that appeared in Colonial newspapers see Colonial American Newspapers: Character and Content by David A. Copeland Newark: University of Delaware Press: 1997. For an analysis of the characteristics of early American journalism see Charles E. Clark's essay "Early American Journalism: News and Opinion in the Popular Press" in Volume I of A History of the Book in America (Cambridge: American Antiquarian Society and Cambridge University Press. 2000). For an analysis of the role of printers in the American Revolution see The Press and the American Revolution (Worcester, Mass.,1980) and Prelude to Independence: The Newspaper War on Britain, 1764-1776 by Arthur M. Schlesinger (New York, 1958). The best description of the process and trade of printing remains The Colonial Printer by Lawrence C. Wroth (New York, 1931, 1996).

3Boston Newsletter, Boston, Mass, April 20, 1775, p. 3

4 Thomas, Isaiah, The History of Printing in America with a Biography of Printers, and an Account of Newspapers, Worcester, Mass, Isaiah Thomas, Jr., 1810, p. 384

5 Mott, Frank Luther, The Newspaper Coverage of Lexington and Concord, Orono, ME: University Press. 1944, p. 503

6 Massachusetts Spy, Worcester, Mass., May 3, 1775, p. 3

7 Nichols, Charles L. "Some Notes on Isaiah Thomas and his Worcester Imprints," from the Proceedings of the American Antiquarian Society, at the Semi -Annual Meeting, April 25, 1900.