This Headache Is Killing Me: The Bromo-Seltzer Poisonings of 1898

Isaac E. Emerson, the man who patented the formula for Bromo-Seltzer, was as well-known in the late-19th century as Bill Gates is today. Bromo-Seltzer was billed as a cure for exhaustion, headache, insomnia, brain fatigue, loss of appetite and other common complaints. Sold in distinctive little blue bottles, it became a household word through extensive newspaper advertising that extolled its virtues, often in poetic verse:

With nerves unstrung and heads that ache.

Wise women Bromo Seltzer take.

The day before Christmas 1898, a pasteboard box marked Tiffany & Co., addressed to Mr. Harry Cornish and wrapped in plain paper, arrived at the New York Knickerbocker Athletic Club where Mr. Cornish worked. Inside were a two-inch high, sterling candlestick-shaped bottle holder and a blue bottle of what appeared to be a trial-size sample of Bromo-Seltzer. The package bore no mark of the sender. Cornish took the box home and showed the gift to Mrs. Florence Rogers and her daughter Mrs. Kate Adams, who was his aunt. Mrs. Rogers thought it must have been sent by a bashful girl. Cornish left the present in his room and thought no more of it.

Several days later, after a night out at the theater, Mrs. Adams awoke with a headache and, remembering the Bromo-Seltzer in her nephew's room, retrieved the bottle and poured a teaspoon of the contents into a glass of water. Almost immediately after drinking the liquid, she was violently ill and in agonizing pain. Doctor Hitchcock was summoned and attempted to pump the patient's stomach but found her unresponsive. The doctor, wondering what she had consumed, took a small sip from the glass, collapsed and almost became a second victim himself. It was later determined that the bottle contained not Bromo-Seltzer but potassium cyanide. Apparently someone had mistakenly killed Adams in an attempt to poison Cornish.

March 15, 1899

The tragedy captured the attention of the public, and news stories appeared across America, unfolding every new clue to the identity of the mystery murderer. Hysteria nearly gripped the nation as reports broke out of similar poisoning cases, though none were connected to the Adams case. One instance involved a gentleman who had mistaken a bottle of corrosive sublimate (or mercuric chloride) for a bottle of Bromo-Seltzer. Another headline read, "Poisoning By Mail a Fad."

The investigation was long and intense with every salacious detail spelled out in the papers. Mr. Cornish eventually identified Mr. Roland B. Molineux as the most likely suspect due to the enmity between them. Molineux was tried in both the courts and the news media. Isaac Emerson, one of a number of so-called expert witnesses, was called to testify about his product. Each scandalous revelation was widely reported as the trial dragged on for months.

(Anaconda, MT), December 30, 1899

Unsurprisingly, Molineux was convicted, sentenced to death and sent to Sing Sing Prison to await his fate. In New York, at the time, prisoners in solitary confinement were allowed communications only from family members or their attorney. When a small box arrived, addressed to the inmate, it was opened by the warden, and found to contain a bottle of Bromo-Seltzer. On the wrapper were the words, "Brace up Roland."

(New Haven, CT), March 8, 1900

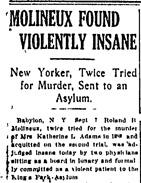

After four years in prison and two trials, Molineux was acquitted of the charges. Years of his name in the headlines brought him both fame and misfortune. His father lost a huge sum defending him. His wife, shortly after his release, wed the lawyer who helped her gain a divorce from Molineux. The ordeal changed him. He worked on behalf of other inmates he believed were wrongly convicted, and he used his notoriety to promote a novel, a play and news stories he authored. Yet, he continued to find himself in the spotlight as the man twice tried for the murder of Mrs. Adams. The strain took its toll, and in 1914 he was ruled insane by two physicians and confined to a sanitarium after being arrested for running through the streets half clad and fighting with pedestrians.

(Boston, MA), September 8, 1914

Newspapers mirror for us ourselves as we were and as we are. Time passes but human nature remains unchanged. Perhaps you remember, back in September 1982, when the deaths of seven people in the Chicago area resulted from the Tylenol poisonings. The perpetrator, never caught or charged, had stolen boxes of Tylenol from drug and grocery stores, removed the contents of the capsules and replaced them with potassium cyanide. Johnson & Johnson, the makers of Tylenol, were forced to recall over 31,000,000 bottles valued at over $100,000,000. Roger Arnold, was investigated and cleared of the killings, but as a result suffered a nervous breakdown.

A note, sent to the company demanding $1,000,000 to stop the murders, was determined to having been sent by James W. Lewis. While the authorities could not connect Lewis with the murders, he was convicted of extortion, imprisoned and released in 1995. In February 2009, not long after the 25th anniversary of the Tylenol murders, the FBI searched Lewis's home, apparently part of an ongoing investigation. A website maintained by Lewis's wife, proclaims his innocence and laments the impact of the case on his life. The similarities to the Bromo murders are both striking and discomforting.

It often takes a tragedy to prompt us to action. Just as the numerous deaths before the turn of the last century resulted in more stringent legislation regarding dangerous drugs, the Tylenol killings led to legislative changes in packaging of over-the-counter medications. These changes have had impact on all of us, a fact of which I am reminded of daily as I fumble to open my "childproof" bottle of medication.