An Undergraduate's Reflections on Original American History Research: How Online Access to Historical Newspapers Helped Prepare an Award-Winning Tea Party Study

Of all the events that occurred during America’s colonial era perhaps none more immediately conjures up images than the Boston Tea Party, when patriots boarded English ships to destroy taxed tea. Nearly a year and a half later, on April 19, 1775, the skirmish between those patriots and British Regulars at Lexington and Concord provoked the shot that was heard “around the world,” a story with which many Americans are also familiar. Undoubtedly, these events merit widespread recognition, for both were key developments in the establishment of the United States. However, by moving immediately from the Tea Party to the beginning of the Revolution, one neglects crucial moments during those intervening sixteen months that helped develop a pervasive unity necessary for a successful war with Britain. That unity derived in part from responses to the Tea Act of 1773, efforts that were spearheaded in Boston but not isolated there. Indeed, reactions throughout the colonies testify to Massachusetts’ importance as the first colony to act decisively in response to the tea’s arrival. That significance is manifested most clearly in the inspired attitudes of New Yorkers, whose actions affirm the influence of the Bostonians’ decision. 1

These were the foundational thoughts of my senior thesis at Taylor University, which I presented at the annual Butler University Undergraduate Research Conference in April, 2010, in a paper entitled “Beyond Boston: New York’s Response to the Tea Act and the Development of Colonial Unity.” Although I wanted to focus on New Yorkers’ reaction to the Bostonians’ initiative, an idea inspired by research I had done earlier in the semester for a lecture I gave about the Tea Party’s significance, I was hesitant to commit to such an unfamiliar topic. After all, that New York had its own tea party was news to me when researching for the lecture. More daunting, though, was the specificity of my subject matter, particularly when conducting research at a library designed to serve only 2,000 students. One afternoon, though, I discovered a unique online database of primary sources: Early American Newspapers, Series 1, 1690-1876. No longer was insufficient research material a problem.

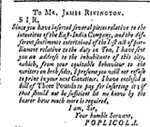

With access to almost any colonial newspaper that I desired, I now had a library of pertinent primary information at my fingertips. Although I could give several examples that speak to the quality of research provided by these sources, three articles suffice to illustrate how this searchable database offered me unique insight into the New Yorkers’ reactions. The first is found in the November 18, 1773, issue of the New York Gazetteer, a paper edited by James Rivington. More loyal to the Crown than most colonial newspapers, the Gazetteer often featured articles sympathetic to England, including one penned by Frederick Pigou and Benjamin Booth, New York consignees responsible for landing the taxed tea. Written under the alias “POPLICOLA,” the article appeals to the colonists’ loyalty, asking how the New Yorkers could purchase smuggled Dutch tea instead of supporting the English product. Reminding the colonists “that not this, or any other province, is your country, but the whole British empire,” Pigou and Booth asserted that by buying English tea, New Yorkers would “not only promote the common good, but their own particular interest also.” 2

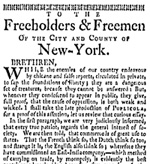

In the epitome of rebuttal, a disgruntled “TRADESMAN” responded to the consignees in the next article, also on the front page. “POPLICOLA has . . . informed us that the English tea . . . is much better than the Dutch tea,” the colonist wrote, “though he has not been so kind as to tell us why.” Maintaining his sarcastic tone, the author, on behalf of many likeminded colonists, observed, “Strange it is that a gentleman who has resided so long in this city should take the inhabitants for perfect idiots!” 3 As they would later display in their response to the tea’s arrival, the New Yorkers certainly were not idiots.

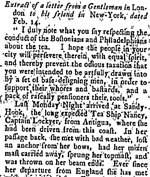

The third article, printed in the April 21, 1774 issue of the New York Journal, encapsulates New Yorkers’ general feelings in response to the tea’s arrival on the Nancy three days earlier. Upon examining the ship’s extensive damage—its arrival had been delayed by nearly four months because of a series of storms—the author compared the Nancy to the boat on which the prophet Jonah attempted to flee from God. “She has met with a continued succession of misfortunes,” the New Yorker observed, “having on Board somewhat worse than a Jonah, which, after being long tossed in the tempestuous ocean, it is hoped, like him, will be thrown back upon the place from whence it came.” Clearly drawing a parallel between Jonah and the tea, the colonist wished that the commodity, once it was returned to Parliament, would “teach a lesson there as useful as the preaching of Jonah was to the Ninevites.” 4 Both of the writer’s prophecies proved true: New Yorkers unloaded the taxed tea into the “tempestuous ocean” and the empty ship’s arrival at London sent a clear message to the Crown.

These articles only begin to scratch the surface of the type of research made possible by the seven online series of Early American Newspapers. The amount of valuable information contained in these issues and the ease with which it can be browsed and searched cannot be overemphasized. In my case, just as the Tea Party was not confined to Boston, thanks to the digitization of Early American Newspapers, neither was my research limited to the print and microfilm materials held by my own small institution’s library.

Footnotes

1 David A. Brooks, Beyond Boston: New York’s Response to the Tea Act and the Development of Colonial Unity, HIS 341: Colonial America, Taylor University, Fall 2009.

2 POPLICOLA, “To The worthy Inhabitants of the City of New-York,” New York Gazetteer, November 18, 1773, page 1.

3 TRADESMAN, “To the Freeholders and Freemen of the City and County of New York,” New York Gazetteer, November 18, 1773, page 1.

4 “Extract of a letter from a Gentleman in London to his friend in New York, dated Feb. 14,” New York Journal, April 21, 1774, page 3.