The Development of the American Advertising Card

Advertising cards, also known as trade cards, were issued by businesses to advertise their wares and services. They appeared in England in the seventeenth century, eventually following the colonists to America and coming into use here in the early eighteenth century. Advertising cards changed little for more than 100 years, but then made up for lost time by evolving rapidly over the last quarter of the nineteenth century. And then, they all but disappeared.

At every stage of their existence, American trade cards reflected the state of the country. Before there were large companies, trade cards advertised individual merchants and craftsmen. Cards were produced by local printers and engravers, solely in black and white and usually without illustration.

Over the course of the nineteenth century, businesses grew in size. This expansion included printing establishments, where advances in printing technology yielded quality improvements and the option of color. All of this is documented on advertising cards. And as national pride, power, and confidence swelled, the ethos of “America Ahead” imbued many trade cards of the late nineteenth century.

The American Broadsides and Ephemera, Series I digital archive contains 129 different genre-based repositories, one of which is Advertising Cards. Entries for nearly four thousand trade cards reside therein. We will use six examples from this archive to map the development of the American advertising card.

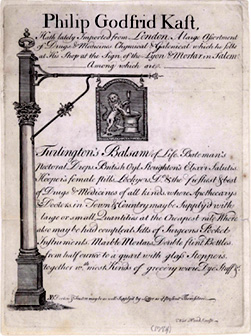

1774: Philip Godfrid Kast, Pharmacist

Few early cards were illustrated. However, this card for Salem pharmacist Philip Kast shows his “Sign of the Lyon & Mortar”—exactly what a potential customer would use to locate Kast’s shop, since numbered street addresses were not yet established. Many of Kast’s products are identified on the card (actually a sheet, rather than a card per se). Like many advertisements of the Colonial era, this card lists items imported from England.

The Philip Kast trade card, an example of copperplate engraving, is signed “Nat. Hurd. Sculp.” This is Nathaniel Hurd, a Boston engraver (or sculptor, hence the “Sculp”) and silversmith. Hurd was an associate of fellow silversmith Paul Revere. Nathaniel learned the trade from his father, Jacob Hurd, producer of a significant portion of all extant Boston silver.

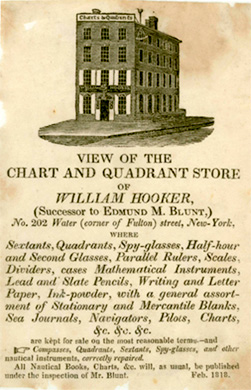

1818: William Hooker, Chart and Quadrant Store

Moving ahead to 1818 and this trade card for William Hooker’s Chart and Quadrant Store in New York, relatively little has changed from the 1774 Philip Kast card. Many of the Chart and Quadrant Store’s items and services are stated, albeit in lettering less stylized than that on the Kast card.

Just as Kast’s business was at the “Sign of the Lyon & Mortar,” the Chart and Quadrant Store had originally called customers to the “Sign of the Quadrant.” A street address is identified on the card shown here, but a close examination of the store image reveals the sign of the quadrant near the upper right of the storefront. This wood-engraved illustration may have been executed by Hooker himself.

William Hooker, successor to Edmund M. Blunt, was Blunt’s son-in-law. The notation that Blunt would continue to oversee production of books and charts was significant, because by 1818 Blunt was the best-known publisher of nautical books and charts in the United States. His American Coast Pilot, first published in 1796, was an important guide to American coastal navigation. Over the years, 21 editions of American Coast Pilot were published.

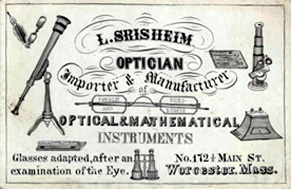

ca. 1845: L. Srisheim, Optician

By the 1840s, the quality and quantity of illustration seen on advertising cards had increased. A trade card for L. Srisheim, a Worcester optician, changes the approach used on the two previous cards by picturing, rather than enumerating, the business’s wares. This is done in a pleasing tableau that nicely balances graphic and text elements.

There was still virtually no color in advertising cards of the 1840s, and wood engraving continued to predominate. The overwhelming majority of advertisers remained small businesses and sole proprietorships.

1865: William Knabe & Co., Pianos

Now we have some real progress! Color, for one thing. Printing advances allowed color to enter the picture (literally) in the 1850s, although in terms of advertising cards, color was seen primarily in the clipper ship cards issued to promote the clippers’ voyages from New York and Boston to San Francisco. [See Images of American Historical Figures on 19th-Century Ship Cards published in The Readex Report, Vol. 1, Issue 4, 2006]

The advent of color was largely tied to the development of lithography as a printing technique. The Knabe card represents a combination of printing processes, with a lithographed central image surrounded by lettering produced by wood engraving. It is printed on heavy coated card stock, much like the clipper ship cards that continued to flow from printers such as George Nesbitt in New York and George Watson in Boston.

The William Knabe card reveals changes in other aspects of advertising cards. Note that now, in 1865, the business advertised is not that of a lone proprietor, but a full-fledged company. And, unlike earlier cards that targeted locals, this Knabe card was distributed in Baltimore, New York, and probably other cities as well.

Nor was the printer of this card a small-shop operation. A. Hoen & Co., already a sizeable firm in 1865, would be Baltimore’s largest printing operation for the rest of the nineteenth century.

Wm. Knabe & Co. pianos are still sold today, manufactured by Samick Musical Instruments, Ltd., of South Korea. Samick has an ownership stake in Steinway Musical Instruments, Inc., whose brands include Steinway & Sons, Ludwig, and C. G. Conn.

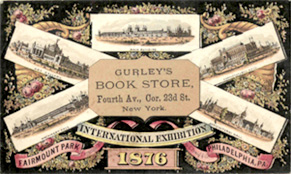

1876: Gurley’s Book Store

The International Exhibition of Arts, Manufactures and Products of the Soil and Mine, or Centennial Exhibition, opened in Philadelphia on May 10, 1876. This was the first bona fide world’s fair to be held in the United States. With ten million visitors—equal to 20% of the entire American population—the event was a great success.

As it happened, the Centennial Exhibition was a coming-out party for the trade card. Full-color printing, accomplished by chromolithography, was now widely available, and the advertising card was an ideal medium to employ this technology. From 1876 until the mid-1890s, multicolor trade cards of increasing quality flooded the United States.

Large numbers of cards were distributed by exhibitors on the Centennial Exhibition grounds, as well as by local Philadelphia businesses. In addition, several printers offered stock cards for use by advertisers anywhere, large and small. These cards generally showed an array of the major Centennial buildings, with one or more blank spaces for an advertiser to fill as desired. The reverse of the card could be utilized by the advertiser as well.

The Gurley’s Book Store card shown here is a stock card printed by L. Prang & Co. of Boston. Louis Prang was one of the premier lithographers in the United States. Prang developed a number of chromolithographic innovations during his career, and in 1875 became the first American printer of Christmas cards.

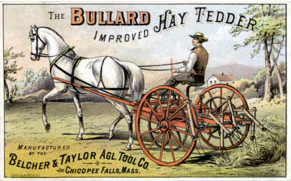

ca. 1885: Belcher & Taylor Bullard Hay Tedder

By the mid-1880s, trade cards were ubiquitous, advertising just about every business, product, and service imaginable. Chromolithography had reached its zenith, and people delighted in beautifully printed cards, so much so that saving them in family albums became a national pastime.

The Belcher & Taylor Bullard Hay Tedder card represents the culmination of the art of the trade card, concurrently reflecting the rising tide of the American nation. Belcher & Taylor was one of the largest manufacturers of agricultural equipment in the United States. The card shows a confident, prosperous-looking farmer—emblematic of a successful America—guiding his tedder through his fields.

The Belcher & Taylor card is well-designed, with the arched lettering in the upper right and lower left nicely framing the central image. The color is subtle but effective, and kept in perfect register by Gies & Co. of Buffalo, who specialized in printing for farm machinery companies.

Advertising card use dropped off dramatically after 1900. The printing advances that had supported trade cards now facilitated magazines, catalogs, and newspapers as the preferred advertising media.

Conclusion

Using only a tiny fraction of the American Broadsides and Ephemera, Series I archive’s digital entries for advertising cards, we have illustrated at a high level the evolution of trade cards over a century of American economic and societal progress. This leaves plenty of images for researchers to discover, study, and savor!