The Nanjing Atrocities Reported in the U.S. Newspapers, 1937-38

The German invasion of Poland on September 1, 1939, is conventionally regarded as the starting point of World War II. However, war broke out much earlier in Asia. On July 7, 1937, after claiming that one of its soldiers was missing, the Japanese launched attacks at the Chinese positions near the Marco Polo Bridge in a Beijing southwestern suburb. During the following weeks, the Japanese continued with their attacks in North China, capturing Beijing, Tianjin, and other cities in the region.

While Japanese forces were engaged in conquering warfare in North China, tension built up down south in the Shanghai area. Shots were fired on August 9, 1937, in a clash in which two Japanese marines and one member of the Chinese Peace Preservation Corps were killed near the entrance to the Hongqiao Airfield in a Shanghai suburb. After rounds of unsuccessful negotiation, the clash led to the outbreak of hostilities in Shanghai on August 13. Street fighting soon escalated to ferocious urban battles when both sides rushed in divisions of reinforcements.

With heavy casualties inflicted on both sides, the war continued for three months before Shanghai fell to the Japanese on November 12, 1937. Even though Chinese troops fought persistently for months in and around Shanghai, they failed to put up effective resistance west of Shanghai, due to a chaotic and hasty evacuation. Taking advantage of the situation, the Japanese swiftly chased fleeing Chinese troops westward, reaching the city gates of China’s capital, Nanjing, on December 9.

As the Japanese swept the Yangtze valley, such atrocities as killing, raping, looting, and burning were reported to have taken place in the cities, towns, and villages through which Japanese soldiers had travelled. The magnitude and brutality peaked after the Japanese captured Nanjing on December 13, 1937. An American diplomat reported that:

the Japanese soldiers swarmed over the city in thousands and committed untold depredations and atrocities. It would seem according to stories told us by foreign witnesses that the soldiers were let loose like a barbarian horde to desecrate the city. Men, women and children were killed in uncounted numbers throughout the city. Stories are heard of civilians being shot or bayoneted for no apparent reason.[1]

According to the judgment by the International Military Tribunal for the Far East in 1948:

Estimates made at a later date indicate that the total number of civilians and prisoners of war murdered in Nanking and its vicinity during the first six weeks of the Japanese occupation was over 200,000. That these estimates are not exaggerated is borne out by that fact that burial societies and other organizations counted more than 155,000 bodies which they buried. They also reported that most of those were bound with their hands tied behind their backs. These figures do not take into account those persons whose bodies were destroyed by burning or by throwing them into the Yangtze River or otherwise disposed of by the Japanese.[2]

During the siege and fall of Nanjing, as well as the ensuing massacre, 27 Westerners, including five American and British journalists, chose to stay inside the city walls. The journalists stayed to cover the Nanjing battle and the city’s expected fall. When the Nanjing carnage unfolded in front of them, they immediately took to their pens, though they tried in vain to find a way to send out the reports from the fallen city. On December 15, Archibald Trojan Steele of the Chicago Daily News, Frank Tillman Durdin of the New York Times, Arthur von Briesen Menken of the Paramount Newsreel, and Leslie C. Smith of Reuters managed to leave for Shanghai by USS Oahu and HMS Ladybird, while Charles Yates McDaniel of the Associated Press went to Shanghai by Japanese destroyer Tsuga the following day. It was the five American and British correspondents who first broke the news of the Nanjing carnage while it was still in progress, hoping to expose the atrocities to the outside world.

Once on board Oahu, Steele succeeded in convincing the gunboat’s radio operator to cable to Chicago his dispatch which appeared in the Chicago Daily News on December 15, 1937. He reported that the “story of Nanking’s fall is a story of indescribable panic and confusion among the entrapped Chinese defenders, followed by a reign of terror by the conquering army that cost thousands of lives, many of them innocent ones,” because the Japanese “chose the course of systematic extermination.” “Streets throughout the city were littered with the bodies of civilians and abandoned Chinese equipment and uniforms,” and the “last thing we saw as we left the city was a band of 300 Chinese being methodically executed before the wall near the waterfront, where already corpses were piled knee deep.” [3] On December 18, Steele published another report, in which he told the readers that

Patrols of Japanese soldiers moved through the streets, searched houses and arrested droves of people as suspected plainclothes soldiers. Few of them ever came back but those who did said their companions had been slaughtered without even a summary trial. I witnessed one of these execution parties and I have seen the grim results of others. What is more difficult, I have had to listen to the wailing and sobbing of women pleading for the return of sons and husbands they will never see again. [4]

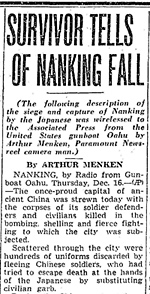

The other correspondent who managed to cable out a report on the USS Oahu was Menken, who indicated in his dispatch first published in the Seattle Daily Times on December 16:

Scattered through the city were hundreds of uniforms discarded by fleeing Chinese soldiers who tried to escape death at the hands of the Japanese by substituting civilian garb....To make sure that the watchman at the American embassy was not executed for having arms, McDaniel took away his pistol and made him stay inside. This probably saved his life. All Chinese males found with any signs of having served in the army were herded together and executed. [5]

The other journalists dispatched cables back to their home agencies immediately after their arrival in Shanghai. McDaniel described his observations in diary form which first appeared in the Seattle Daily Times on December 17:

Dec. 14–Watched Japanese throughout city looting. Saw one Japanese soldier who had collected $3,000 after demanding civilians in safety zone to give up at bayonet point. Reached north gate through streets littered with dead humans and horses. Saw first Japanese car enter gate, skidding over smashed bodies. Finally reached waterfront, boarded Japanese destroyer; told Panay has been sunk.

Dec. 15–Chinese thankfulness siege over became despairing disillusionment. Went with embassy servant to look for her mother. Found her body in ditch. Embassy office boy's brother also found dead. This afternoon saw some of the soldiers I helped disarm dragged from houses, shot and kicked into ditches. Tonight saw group of 500 civilians disarmed soldiers, hands tied, marched from safety zone by Japanese carrying Chinese “big swords.” None returns. Many Chinese seized, led away despite Japanese flags placed in houses and huts.

Japanese soldiers attempted to enter American embassy, where I was living, but when I refused entry they withdrew. The embassy Chinese staff was marooned without water and fearful to step outside, so spent an hour filling buckets from the street well and bringing into the embassy.

Dec. 16–Before departing for Shanghai, Japanese consul brought “no-entry” notices, which posted on embassy property. En route to the river, saw many more bodies in the streets. Passed a long line of Chinese, hands tied. One broke away, ran and dropped on his knees in front of me, beseeching me to save him from death. I could do nothing. My last remembrance of Nanking: Dead Chinese, dead Chinese, dead Chinese. [6]

In the Springfield Republican the following day, McDaniel published another report in which he indicated that the “tragic aftermath of the fall of Nanking was witnessed by this correspondent, who reached Shanghai yesterday on a Japanese destroyer. I saw four days marked by Japanese looting and wholesale executions of Chinese.” [7]

Though Durdin’s report did not appear in print until December 18, 1937, his accounts provide more detailed information along with analysis:

Wholesale looting, the violation of women, the murder of civilians, the eviction of Chinese from their homes, mass executions of war prisoners and the impressing of able-bodied men turned Nanking into a city of terror.…

In one building in the refugee zone 400 men were seized. They were marched off, tied in batches of fifty, between lines of riflemen and machine gunners, to the execution ground.

Just before boarding the ship for Shanghai the writer watched the execution of 200 men on the Bund. The killings took ten minutes. The men were lined against a wall and shot. Then a number of Japanese, armed with pistols, trod nonchalantly around the crumpled bodies, pumping bullets into any that were still kicking.[8]

In the same report, Durdin commented, “By despoiling the city and population the Japanese have driven deeper into the Chinese a repressed hatred that will smolder through years as forms of the anti-Japanism that Tokyo professes to be fighting to eradicate from China.”[9] Then, he went on with detailed descriptions of Japanese atrocities:

Thousands of prisoners were executed by the Japanese. Most of the Chinese soldiers who had been interned in the safety zone were shot en masse. The city was combed in a systematic house-to-house search for men having knapsack marks on their shoulders or other signs of having been soldiers. They were herded together and executed.

Many were killed where they were found, including men innocent of any army connection and many wounded soldiers and civilians. I witnessed three mass executions of prisoners within a few hours Wednesday. In one slaughter a tank gun was turned on a group of more than 100 soldiers at a bomb shelter near the Ministry of Communications.

A favorite method of execution was to herd groups of a dozen men at entrances of dugouts and to shoot them so the bodies toppled inside. Dirt then was shoveled in and the men buried....

Civilian casualties also were heavy, amounting to thousands. The only hospital open was the American-managed University Hospital and its facilities were inadequate for even a fraction of those hurt.

Nanking’s streets were littered with dead. Sometimes bodies had to be moved before automobiles could pass.

The capture of Hsiakwan Gate by the Japanese was accompanied by the mass killing of the defenders, who were piled up among the sandbags, forming a mound six feet high. Late Wednesday the Japanese had not removed the dead, and two days of heavy military traffic had been passing through, grinding over the remains of men, dogs and horses.

The Japanese appear to want the horrors to remain as long as possible, to impress on the Chinese the terrible results of resisting Japan....

Nanking today is housing a terrorized population who, under alien domination, live in fear of death, torture and robbery. The graveyard of tens of thousands of Chinese soldiers may also be the graveyard of all Chinese hopes of resisting conquest by Japan. [10]

Durdin wrote another lengthy article about the Nanjing carnage. The article was air-mailed from Shanghai to New York on December 22, 1937, but it was not published until January 9, 1938. Although the article places more emphasis on the analysis of the Nanjing battle in terms of military strategies, it gives further descriptions of the atrocities committed by the Japanese:

In taking over Nanking the Japanese indulged in slaughters, looting and raping exceeding in barbarity any atrocities committed up to that time in the course of the Sino-Japanese hostilities. The unrestrained cruelties of the Japanese are to be compared only with the vandalism in the Dark Ages in Europe or the brutalities of medieval Asiatic conquerors.

The helpless Chinese troops, disarmed for the most part and ready to surrender, were systematically rounded up and executed. Thousands who had turned themselves over to the Safety Zone Committee and been placed in refugee centers were methodically weeded out and marched away, their hands tied behind them, to executive grounds outside the city gates.

Small bands who had sought refuge in dugouts were routed out and shot or stabbed at the entrances to the bomb shelters. Their bodies were then shoved into the dugouts and buried. Tank guns were sometimes turned on groups of bound soldiers. Most generally the executions were by shooting with pistols.

Every able-bodied male in Nanking was suspected by the Japanese of being a soldier. An attempt was made by inspecting shoulders for knapsack and rifle butt marks to single out the soldiers from the innocent males, but in many cases, of course, men innocent of any military connection were put in the executed squads. In other cases, too, former soldiers were passed over and escaped.

The Japanese themselves announced that during the first three days of cleaning up Nanking 15,000 Chinese soldiers were rounded up. At the time, it was contended that 25,000 more were still hiding out in the city.

These figures give an accurate indication of the number of Chinese troops trapped within the Nanking walls. Probably the Japanese figure of 25,000 is exaggerated, but it is likely that about 20,000 Chinese soldiers fell victim to Japanese executioners.

Civilians of both sexes and all ages were also shot by the Japanese. Firemen and policemen were frequent victims of the Japanese. Any person who, through excitement or fear, ran at the approach of the Japanese soldiers were in danger of being shot down. Tours of the city by foreigners during the period when the Japanese were consolidating their control of the city revealed daily fresh civilian dead. Often old men were to be seen face downward on the pavements, apparently shot in the back at the whim of some Japanese soldier.[11]

Like his American colleagues, Reuter’s correspondent Smith, once he got to Shanghai, wasted no time in sending his witness accounts to London. In his report, which appeared on December 18, 1937, Smith testified that “anyone caught out of doors without good reason was promptly shot,” and “the Japanese began a systematic searching out of anyone even remotely connected with the Chinese Army.”[12] Smith observed that “At the Hsiakwan gate leading to the river the bodies of men and horses made a frightful mass 4 ft. deep, over which cars and lorries were passing in and out of the gate.” [13]

Meanwhile, Steele continued to be haunted by the tragic images of Nanjing and published two more articles, describing what he had witnessed. In the first published on February 3, 1938, Steele asserted that “hundreds of innocent civilians were arrested and massacred during the course of this reign of terror.”[14] In his second article, Steele gave the following first-hand account:

I witnessed one mass execution. The band of several hundred condemned men came marching down the street bearing a large Japanese flag. They were accompanied by two or three Japanese soldiers, who herded them into a vacant lot. There they were brutally shot dead in small groups. One Japanese soldier stood over the growing pile of corpses with a rifle pouring bullets into any of the bodies which showed movement.

This may be war to the Japanese, but it looked like murder to me. [15]

After the five newsmen departed, the reign of terror continued unabated. However, still trapped in Nanjing 22 Westerners, including 14 Americans. Not only were they forbidden to leave the city, but they had no means of communicating with the rest of the world. They remained in isolation until three American diplomats returned to Nanjing to re-open the U.S. Embassy January 6, 1938. Only then were they able to smuggle out atrocity reports to Shanghai through diplomatic channels.

On January 24, 1938, Hallet Abend, a New York Times China correspondent stationed in Shanghai, reported that the “summary of conditions in China’s former capital which is arriving at Shanghai from missionaries and welfare workers who risked their lives to administer refugee camps during the siege, and other reports from consular and other foreign officials now residing in Nanking, can scarcely all be malicious, yet all these reports agree and all contain eye witness accounts of the horrible brutality and unrestrained license of the Japanese forces presently in Nanking.” Japanese soldiers, Abend wrote, “were out of hand, and daily criminally assaulting hundreds of women and very young girls,” and “as late as January 20 the reign of lawlessness and bestiality was still continuing unchecked…” [16]

In the same report, Abend indicated that “foreign correspondents in Shanghai are forbidden under the Japanese censorship to cable stories appertaining to the Nanking atrocities while foreign-owned Shanghai newspapers fearlessly declare the present conditions in the Nanking area are a disgrace to the Japanese army and tend utterly to destroy the army’s reputation for decency and good behavior.” [17]

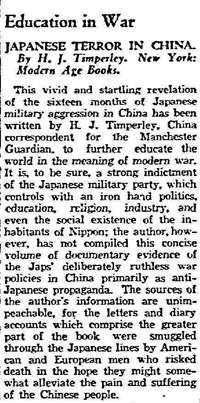

The Japanese censorship that prohibited cabling atrocity reports overseas, however, triggered Harold John Timberley, China correspondent of the Manchester Guardian in Shanghai, to collect eye-witness accounts from various sources and compile them into a book. He managed to airmail his manuscript to London and have the book published in both London and New York in November 1938. As soon as the book’s American edition was released under the title Japanese Terror in China, book reviews appeared in newspapers across the United States. One review in the Dallas Morning News considers the book an effort to “educate the world in the meaning of modern war,” and the “sources of the author’s information are impeachable, for the letters and diary accounts which comprise the greater part of the book were smuggled through the Japanese lines by American and European men who risked death in the hope they might somewhat alleviate the pain and suffering of the Chinese people.”[18]

Another review in Portland’s Sunday Oregonian includes the following quotation from the book:

I have already described the conditions at the gate––we actually had to drive over masses of dead bodies to get through.…Soldiers were taking all 1,300 men in one of our camps to shoot them. Not a whimper from the entire throng. … That morning the cases of rape began to be reported. Over a hundred we knew of were taken away by soldiers, seven of them from the university library....At our staff conference at four we could hear the shots of the execution squad nearby.

December 17––A rough estimate would be at least a thousand women raped last night and during the day. Resistance means the bayonet.…A boy of five stabbed with a bayonet five times.…Some houses are entered five to ten times a day and the poor people looted and robbed and the women raped.…Went with Sperling to see fifty corpses in some ponds. Were they used for saber practice? [19]

On February 20, 1938, George Ashmore Fitch, one of the 14 Americans in Nanjing, was eventually permitted to leave for Shanghai. When he left Nanjing on a crowded Japanese military train, Fitch succeeded in smuggling out eight reels of 16 mm negative movie film of atrocity cases mainly shot at the University of Nanking Hospital by John Gillespie Magee, an American Episcopal missionary in Nanjing. [20] After brief stays at Shanghai, Hong Kong, and Guangzhou, Fitch took the “Philippine Clipper,” a trans-Pacific flight, to arrive in San Francisco on March 9, 1938, and flew to Washington D.C. on March 17 to confer with State Department officials and give them a first-hand account of the Japanese occupation of Nanjing. He toured the United States to give speeches and show the movies he had smuggled out to audience in San Francisco, Los Angles, D.C., New York City, Chicago, Cleveland, Columbus, Portland, Seattle, and many other places.[21]

His speech tour was actively covered by local newspapers. In Cleveland, Fitch told his audience at Cleveland Heights Presbyterian Church that the “destruction of Nanking was the blackest page in modern history…The Japanese for two months kept up continuous looting, burning, robbing and murdering….Chinese men by the thousands were taken out to be killed by machine guns or slaughtered for hand grenade practice.…The poorest of the poor were robbed of their last coins, deprived of their bedding and all that they could gather out of a city systematically destroyed by fire. There were hundreds of cases of bestiality inflicted upon Chinese women.” [22]

While Fitch was speaking on the West Coast, The San Francisco Chronicle published a story by him in its Sunday Supplement, This World, on June 11, 1938, under the title, “The Rape of Nanking.” According to Fitch, after Japanese soldiers poured into Nanjing city gates on December 13, 1937, “I heard the cries of tens of thousands of women kneeling and praying for help which we were helpless to give. First, their husbands and sons were torn from them and ruthlessly murdered. Then night after night squads of Japanese soldiers would invade the neutral zone and drag away hundreds of them, crying hysterically, to be subjected to unspeakable indignities. Theirs was a fate worse than death.” [23]

Footnotes:

[1] James Espy, “The Conditions at Nanking, January 1938,” January 25, 1938, p. 8, (Department of State File No. 793.94/12674), Microfilm Set M976, Roll 51, Record Group 59, the National Archives II, College Park, MD.

[2] R. John Pritchard and Sonia Magbanua Zaide, The Tokyo War Crimes Trial, Vol. XX Judgment and Annexes, New York: Garland Publishing Inc., 1981, p. 49, 608.

[3] A. T. Steele, “Japanese Troops Kill Thousands; ‘Four Days of Hell’ in Captured City Told by Eyewitness; Bodies Piled Five Feet High in Streets,” The Chicago Daily News, December 15, 1937, p. 1.

[4] A. T. Steele, “Tells Heroism of Yankees in Nanking,” The Chicago Daily News, December 18, 1937, p. 1.

[5] Arthur Menken, “Survivor Tells of Nanking Fall,” The Seattle Daily Times, December 16, 1937, p. 4, and Arthur Menken, “Witness Tells Nanking Horror as Chinese Flee,” The Chicago Daily Tribune, December 17, 1937, p. 4.

[6] C. Yates M’Daniel, “Newsman’s Diary Describes Horrors in Nanking,” The Seattle Daily Times, December 17, 1937, p. 12.

[7] C. Yates McDaniel, “Nanking Hopes Japanese Will Mitigate Harshness,” The Springfield Daily Republican (Springfield, Mss.), December 18, 1937, p. 2.

[8] F. Tillman Durdin, “Butchery Marked Capture of Nanking,” The New York Times, December 18, 1937, pp. 1 and 10.

[9] Ibid., p.

[10] Ibid.

[11] F. Tillman Durdin, “Japanese Atrocities Marked Fall of Nanking after Chinese Command Fled,” The New York Times, January 9, 1938, p. 38.

[12] “Terror in Nanking,” The Times, December 18, 1937, p. 12.

[13] Ibid.

[14] A. T. Steele, “Panic of Chinese in Capture of Nanking,” The Chicago Daily News, February 3, 1938, p. 2.

[15] A. T. Steele, “Reporter Likens Slaughter of Panicky Nanking Chinese to Jackrabbit Drive in U.S.,” The Chicago Daily News, February 4, 1938, p. 2.

[16] Hallet Abend, “Invaders Despoil Cringing Nanking,” The Oregonian (Portland, OR), January 25, 1938, p. 2.

[17] Ibid.

[18] “Education in War,” The Dallas Morning News, December 11, 1938, p. 6-II.

[19] “Documents on Nanking,” The Sunday Oregonian, December 4, 1938, p. 2.

[20] “Nanking’s Fall to Be Told,” The Los Angeles Times, March 18, 1938, p. 11, and “Coast Survey Scheduled for Youths’ Summer Camps,” The Los Angeles Times, March 28, 1938, p. 11.

[21] Suping Lu, They Were in Nanjing: The Nanjing Massacre Witnessed by American and British Nationals, Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press, 2004, p. 105.

[22] “Eye-Witness Tells of Horror Seen in Fall of Nanking,” The Cleveland Plain Dealer, May 23, 1938, p. 8.

[23] George A. Fitch, “The Rape of Nanking,” This World, Sunday Supplement to The San Francisco Chronicle, June 11, 1938, p. 16.