Cycling Champion Major Taylor and the African American Press

As a superstar athlete in the most popular sport of his era, 1899 world bicycling champion Major Taylor saw his racing victories well chronicled in mainstream newspapers as well as cycling publications. But it was the African American press, less concerned with the play by play, which revealed a more layered portrait of the black rider balancing on the knife edge of Jim Crow racial segregation.

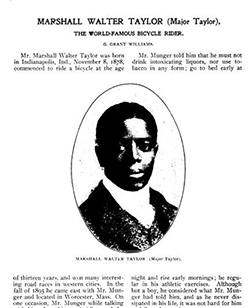

Born in 1878 in Indiana, Marshall W. “Major” Taylor moved as a teenager to Worcester, Massachusetts, with his cycling mentor and employer, who was opening a bicycle factory there. Although “whites only” policies kept Taylor off certain racetracks and hindered him while traveling on the national circuit—he couldn’t always get a hotel room or a meal—“the Worcester whirlwind” was popular with spectators, and promoters cashed in on his box-office draw.

The 1890s bicycle boom preceded the advent of automobiles and airplanes, and sports fans were thrilled by the sheer speed of cyclists. Hostility toward Taylor from some white riders—dirty and dangerous tactics, threats, and even physical assault—only heightened the drama.

A steadfast Baptist, Taylor refused to race on the Sabbath. For that reason he turned down lucrative offers to compete in Europe, where big meets took place on Sundays. When one such offer was on the table in early 1900, “Taylor was annoyed by rumors published in the New York World and the Worcester Spy suggesting that he was weakening in his stand against Sunday racing and had, in fact, capitulated,” Andrew Ritchie wrote in the 1988 biography Major Taylor: The Extraordinary Career of a Champion Bicycle Racer.

“You find the tone in the black publications more personal...and ultimately more opinionated,” said Todd Balf, author of the 2008 book Major: A Black Athlete, A White Era, and the Fight to Be the World’s Fastest Human Being, in a recent interview.

On January 13, 1900, a sports column in The Freeman, the leading African American newspaper in Indianapolis, reprinted the New York World’s piece asserting that “love of fame and a thirst for coin have conquered the religious scruples of Major Taylor.” A subsequent column in The Freeman under the same byline, Ned LMO Bee, “becomes very much an editorial,” Balf said, “basically saying I respect him about his religious principles, but there’s something greater at stake here.” The Feb. 10 column said that religious scruples are one thing, but it would be a mistake for Taylor to miss the opportunity to race the world’s top white riders “abroad where there exists no prejudice.” The column concluded: “Go to Europe, Major, and show the world that you are without a peer.”

The Freeman’s take shows how Taylor’s “example is clearly influential in the black community,” Balf said. “He means something more to this community.”

Taylor did not go to Europe that year. In 1901, he finally negotiated a contract to race in France that specified no Sunday racing, and he went on to beat champion after champion across the Continent. Balf wonders how much The Freeman’s urging may have influenced Taylor’s climactic career move, “opening his eyes to a greater role.”

When Taylor returned from Europe in July 1901, he was “almost immediately embroiled in a new round of bureaucratic squabbling with the National Cycling Association,” biographer Ritchie wrote. Taylor was exhausted and submitted a doctor’s note to excuse him from races on the national circuit. The NCA insisted his contract required him to race “sick or well,” and imposed hefty fines for missed appearances. “Taylor was incensed,” Ritchie wrote, and threatened to retire.

The black press defended Taylor from the establishment spin on the dispute. On July 20, 1901, The Freeman column Sport quoted “an Eastern white daily paper” that essentially had called Taylor a spoiled crybaby and said good riddance if the racing board’s actions made him quit the sport. In response, The Freeman columnist noted that the NCA had repeatedly turned a blind eye to white riders’ fouls on Taylor, and said Taylor would be right to retire (and could afford to), given the racism and injustice directed at him. “That’s right Major, retire,” the column concluded. “You’ve got money, now live easy. These fellows are jealous of your honors and prejudiced to your color.”

Even Cycle Age deemed the fines an insult and accused the NCA of “modern slavery,” Ritchie wrote, but ultimately, “Taylor swallowed his pride and paid the fines” rather than risk being suspended.

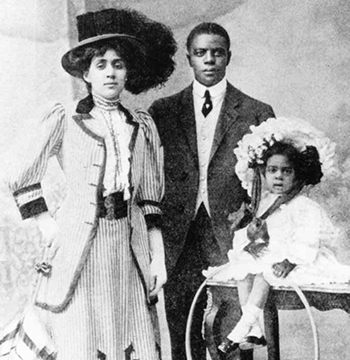

The African American press served not only as defender but as image maker. Major Taylor’s marriage to Daisy Victoria Morris of Connecticut in March 1902 naturally aroused curiosity about the bride. The Colored American Magazine, run by a former editor of The Freeman, “was given the exclusive,” according to Balf’s book. The September 1902 article by G. Grant Williams outlined Daisy’s private education and social refinement: It said she was a graduate of the Hudson Academy and “best all round girl athlete” at an unnamed college. It said she had been active in the Amphion Social Club and the Ladies’ Auxiliary of the Sumner Club in Hartford. The magazine went on, “Mrs. Taylor is a most beautiful woman, an ideal hostess, a charming and brilliant conversationalist.”

Balf set out to verify the details of Daisy’s background, “and I couldn’t,” he said. “I couldn’t find the sort of socialite connections she supposedly had.” State and federal census reports, city directories and other documents told a different story. She was the child of a single mother and a white father, name unknown, raised in a seedy part of Hudson, N.Y. The Hudson Academy “had closed before she was of school age. In Hartford, as in Worcester, she was a servant, not a black debutante,” Balf wrote.

Balf concluded that the story about Daisy that was fed to The Colored American was “creatively altered” to suit the image that a black gentleman needed in those times. “Taylor, as America’s first citizen of color, needed a partner of equal weight, of regalness,” Balf wrote. “Given how popular he was becoming, how important he was as a model within the black community,” Balf explained in a recent interview, a class-appropriate marriage “was important, and he and his handlers recognized that.”

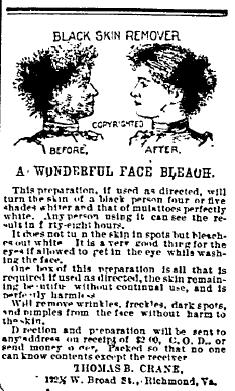

The strata of black society were correlated with skin tone, with a lighter complexion often conveying higher status and privilege, or at least the possibility. African American newspapers in the 1890s consistently ran ads for “black skin remover,” “face bleach” and hair-straightening products. Major Taylor had spent much of his childhood in the home of his father’s wealthy white Indianapolis employers, treated as an equal to the couple’s son, and was stung when he could not join his white playmates at the YMCA. Might he have been tempted to try lightening his own color to make his way in the wider world?

A September 1897 newspaper clipping in Major Taylor’s scrapbook, under the heading “Anecdotes of the Racing Men,” quoted Taylor’s mentor, former racer Louis “Birdie” Munger, relating an attempt to bleach the young racer’s skin.

“Major Taylor was one day refused entry to a race owing to his color,” said Munger. “We told him that we would bleach him and make him white. He took us at our word and submitted to an operation. The mixture was poisonous in the extreme. It was a sort of cream, and for days and days we poured it on the lad. His hair turned a sort of red, and his skin did seem to be turning whiter and whiter. But the solution was working to the detriment of the lad’s health, and we had to stop it. He has never been as dark, though, as he was before the operation. He never got back his old blackness.”

Balf was unable to identify the publication from the typeface and column width, but he said he gave the story credence, and included it in his book, partly because it wasn’t marked with a handwritten “not true” like some other items in Taylor’s scrapbooks, which are held at the Indiana State Museum.

Ritchie said in an interview he would need corroborating evidence to assess the veracity of the skin-bleaching anecdote. He noted it wasn’t in keeping with Munger’s other, sensible guidance for his protégé, such as his advice to refrain from tobacco and liquor. On the other hand, Taylor’s daughter, Sydney Taylor Brown, told Ritchie that she considered her father “color-struck,” meaning, Ritchie wrote in his book, “preoccupied with color and shades of color. He had been attracted to his wife’s fairer complexion and was unhappy that his daughter took after him.” Mrs. Brown told Ritchie that when she was a child, her father would constantly tell her to pull down her hat to protect her skin from the sun. “

The differences in class and social expectations between Taylor and Daisy became more marked as they grew older,” Ritchie wrote, and put a strain on their marriage as Taylor adjusted to his 1910 retirement from bike racing and subsequent life out of the headlines. Business setbacks and illness sapped the former champion’s fortune, and the couple ended up separating. Taylor drove to Chicago, selling copies of his self-published 1928 autobiography out of the trunk of his car, and took a room at the YMCA. In 1932 he died of heart disease in a hospital charity ward, alone and impoverished, at age 53.

The Chicago Defender, a prominent black-owned weekly, published Major Taylor’s obituary, according to Ritchie’s book. Earlier in the century, Balf said, the black press had shown “an uncertainty about how to deal with African American sports heroes,” some of whom were not exemplary in character, and generally held athletes at a distance. The clean-living, churchgoing Major Taylor, the first black world champion in any sport other than boxing, “kind of broke that barrier,” Balf said. “He started to get a lot of attention, full columns, illustrations, exhortations to go to Europe … For me, it established that this was a much bigger figure than just an athlete.”