The Index of Virginia Printing: Building an Online Reference with Print and Digital Resources

How does a researcher handle dated reference works still in print and still widely used?

From the masthead of a Virginia newspaper

This has been a recurring challenge in my twenty years of research into Virginia’s early printing trade. Historians of the Old Dominion have long repeated the assertions of their predecessors with a certain reverence for their closer proximity to the historical past, and so of their forebears’ intrinsic authority. Names like Lyon G. Tyler, Earle Gregg Swem, William G. Stanard, and Lester J. Cappon carry considerable authority among Virginia’s historians, just as those of Charles Evans, Clarence Brigham, Roger P. Bristol, and Winifred Gregory do among bibliographers of early American imprints and newspapers. Their works are magisterial efforts from a time when the now-common computerized collecting and sorting of bibliographic and biographic data was not just unknown, it was unfathomable.

Volumes from Charles Evans'

American Bibliography

To understand the magnitude of what these luminaries accomplished, one need only take the weekly public tour at the American Antiquarian Society (A.A.S.) in Worcester, Massachusetts; you will be shown the thousands of cards used by Charles Evans, its former librarian, to amass his fourteen-volume American Bibliography—written in careful library hand on cards he cut to fit neatly into dozens of girdle boxes. Still, Evans missed a startling number of imprints, simply because those items were not recorded in the places and sources he consulted a century ago. Thus, the “ancient texts” (to use a term favored by Virginia’s early historians) are still in general use today despite inaccuracies, contradictions, and omissions that have never been corrected.

![]()

Printer files at the American

Antiquarian Society in Worcester, Mass.

That revelation came to me through an intensive acquaintance with both manuscript sources and with the imprints produced by the Virginia tradesmen I research. In a quest for accuracy and inclusivity in my doctoral dissertation, I kept a detailed record of each individual I encountered, drawing on any source mentioning that person, including the old standards. Fortunately, using a personal computer to do this meant the tedium of writing up file cards was replaced by simple keystrokes to complete standardized data forms. That collecting process was accelerated by a dissertation fellowship at the A.A.S. where I discovered the Society’s unpublished (and so largely inaccessible) “Printer File”—a card catalogue sorted by name and place, taken from the early American imprints acquired for their collection, whether periodicals, broadsides, pamphlets, or books.

For Virginia, I found cards for nearly 300 individuals working in 29 locales between 1680 and 1820. Yet, even as I recorded this surge of data, I realized I had already located individuals not found in the A.A.S.’s file, and imprints not included in the Evans and Swem bibliographies, raising the question of what I should do with what I found. Obviously, the standard references were flawed, but should I try to correct the errors? And just as obviously, such an effort was far beyond what I needed to do to complete my dissertation project.

My quandary arose just as the digitization of pre-1923 American imprints was beginning in the 1990s. Because that effort was haphazard at first, and not often readily accessible, the data made available by that process were not a large part of the dissertation I completed in 1998. But in the years since, these newly digitized imprints have proved a boon to knowledge of the people involved in Virginia’s early printing trade. More and more of the imprints produced by these tradesmen have found a digital home on the web, and, as they have appeared, my database on Virginia printing has grown as well. Today, the number of Virginia printers I have been able to identify has grown to 513 individuals. The most recent addition was the earliest bookseller I have found in Virginia, a Huguenot whose 1703 estate inventory was recorded in a Henrico County will book, which was then published 125 years ago in an obscure (but now digitized) historical journal.

In keeping in digital form the new records I have generated, my intent has been to eventually produce an online reference work that would combine my recent findings with information from the “old masters.” That goal will finally see fruition (hopefully in 2013) under the auspices of the new Digital Initiatives program at the Virginia Foundation for the Humanities in Charlottesville. Titled The Index of Virginia Printing, this project demonstrates the future of scholarly reference works, particularly ones with a bibliographic or biographic focus. The problem with the “old masters” is the same as that for all printed reference works; regardless of their quality, all such works are obsolete the moment they are published; their unalterable physical form precludes updating or correcting them as new material is uncovered. However, employing a digital format allows for a reference work to be updated regularly. And now the material recorded in my data tables has reached the point where putting the whole project online is not only feasible, but a truly viable alternative to the flawed standard works still in use.

The first part of the Index to reach the web will be discrete biographies of each of the 513 individuals in the database. These biographies represent an essential foundation for a real understanding of the trade: who is doing what when? Recent efforts to digitize early American newspapers (like America’s Historical Newspapers) have produced a flood of personal data on the tradesmen I have been documenting—and, yes, all but three of those individuals are men.

This following biographical entry for one newspaper editor, Leroy Anderson, is an example of the first phase of the Index. The standard reference sources record only Anderson’s role as a schoolmaster who turned briefly to editorial work before returning to his classroom and obscurity. As this sample entry indicates, his story is far more complex and compelling:

011 ANDERSON, LEROY

Editor & Publisher Richmond, Williamsburg

The original editor (1813-15) of Richmond’s first successful daily newspaper, The Daily Compiler, and partner to its printers: Philip DuVal (160) and William C. Shields (422). He was one of many early Virginia journalists who had once been schoolmasters, evidently a highly regarded trait for an editor.

Born in Williamsburg, Leroy was the second son of James Anderson, the master blacksmith who became the state’s Public Armourer during the Revolutionary War. This tradesman’s son was first, and foremost, a scholar and teacher. He attained a classical education early in life, in part, as a result of a residence in Philadelphia; there he met his first wife, one Nancy Shields. On his return to the former state capital, he and his sister Nancy Camp (sometimes spelled Kemp, the widow of George) operated a school for young women—probably in buildings situated on their father’s oversized lot at the corner of Duke of Gloucester and Botetourt streets. Following father James’ death in 1798, Leroy acquired the house on the east side of the lot, Nancy that on the west side. Mrs. Camp used her abode as a boarding house for Leroy’s school, one situated in the building that he also used as a store that sold books, musical instruments, sheet music, and medicines. And when their father’s estate was finally settled in 1806, both siblings retained life-tenancy rights to the Williamsburg houses where they then lived.

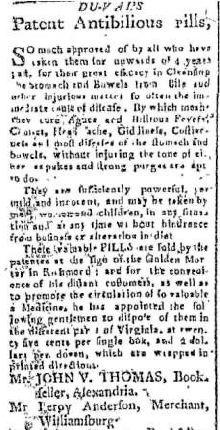

Advertisement from The Times;

and District of Columbia Daily

Advertiser [Alexandria], July 10, 1799

Anderson’s literary reputation continued to grow after his father’s passing, bringing an invitation to write the commemorative ode that was presented at the bicentennial celebration of the Jamestown settlement in 1807. But his attachment to Williamsburg waned with the death of his wife Nancy in 1808. Anderson relocated his school to Richmond, taking up residence in property originally owned by his father. Eventually, his sister Nancy joined him there, though both lived in Williamsburg during the breaks in their school’s terms. Their new “Cornelia Academy” continued until 1819.

Norfolk Gazette and Publick Ledger,

November 18, 1808

The venture, however, was overshadowed by the traumatic loss Anderson suffered with the Richmond Theater fire of December 1811. He attended the ill-fated performance that night with his two young daughters, but escaped the flames with just his youngest one. Daughter Margaret was lost, as were six of his teen-aged pupils, in a conflagration that claimed 76 lives in just ten minutes. In the wake of this tragedy, he quickly remarried, taking as his second wife the widow Hannah Wright Southgate of Richmond, who had lost a brother in the fire; theirs was prolific marriage, bringing five children to adulthood, despite numerous infant deaths that followed their antecedent theater-fire grief.

From Early American Imprints, Series II

After the fire, Anderson also decided to take on a high-minded journalistic venture: The Daily Compiler. His 1813 prospectus promised an unbiased non-partisan newspaper that would present news of the ongoing war with Great Britain in a more timely and less partisan fashion than could Richmond’s three twice-weekly journals; its motto would be Audi et alteram partem (“and hear the other side”). Anderson was shrewd enough to realize that his new daily newspaper could be sustained by the advertising essential to the growing merchant trade in what he called the “emporium of Virginia.” He enlisted printer Philip DuVal (160) to produce the paper as his partner; and its first number appeared May 1, 1813.

Virginia Argus [Richmond] March 25, 1813

But theirs was a problematic relationship. DuVal had access to the capital needed for their publication, as his father, Samuel DuVal, was a major Richmond merchant; yet Philip proved to be “the only son unable to prove himself” in life; by fall the partnership had collapsed and the young printer set out for Staunton to attempt a less stressful weekly there. Meanwhile, Anderson employed a variety of Richmond job-printing offices to publish his daily for the next two years. At the end of 1814, he entered in a new partnership with another craftsman: William C. Shields (422), late of Philadelphia and possibly a relative to Anderson’s first wife. Despite his success, Anderson tired of the editorial grind as the War of 1812 drew to a close. In the summer of 1815 he handed over the reins of the Compiler to another noted Virginia literary figure, Louis Hue Girardin (192), formerly Professor of Modern Languages, History, and Geography at the College of William & Mary, then running the Hallerian Academy in Richmond. This Richmond daily continued under various guises until 1853, when its objective stance finally killed its readership during the growing sectional crisis.

Richmond Commercial Compiler, Dec.18, 1816 (under Girardin)

Anderson returned to the regular seasonality of teaching in Richmond in winter and writing in Williamsburg in summer, but without his sister; Nancy Camp opened her own “Ladies Select School” on Capitol Square in 1815. Meanwhile, Anderson and his new wife operated their “Lyceum Grammar School for Females” until at least 1820; then he established an “Elementary and Classical School” for boys, which continued until at least 1824. And as his commitment to education increased, he proposed (without success) publishing a monthly magazine, The Parnassian, that would promote his pedagogical approach. He also abandoned his non-partisan perspective in 1824, actively embracing the candidacy of John Quincy Adams for president in opposition to the ill-educated Andrew Jackson, joining with men who later became the foundation of Virginia’s Whig party.

In 1835, the aging Anderson was persuaded to move to Alabama to direct the troubled Pineland Academy there. He did not see his beloved Virginia again, dying unexpectedly in Mobile in November 1837 at the age of 67. He left his wife, five children, and a multitude of former students behind—but few took notice back home. Outside of Alabama, his passing was reported only by the National Intelligencer and the Richmond Whig.

Personal Data

Born: 1770, Dec. 6; Williamsburg, Virginia

Married [1]: c. 1794; Williamsburg, Virginia

Married [2]: 1812, Feb. 5; Richmond, Virginia

Died: 1837, Nov. 21; Mobile, Alabama

Children: Leroy Hammond (b. 1814); William Henry (b. 1820); Washington Franklin (b. 1823); Harriet Sophia (m. 1822); Louisa Virginia (m. 1828); several other children died in infancy.

Sources: Imprints; Brigham (2: 1137); Cappon; Hubbard; house-site reports on James Anderson property (Block 10), Rockefeller Library, Colonial Williamsburg; Baker, The Richmond Theater Fire.

Next, a collection of narrative histories for each of the 118 newspapers started in Virginia before 1820 will be added to the Index, with the history for each publication linked to its producers, and vice versa. Early twentieth-century bibliographies cataloguing these newspapers provide some background on their production; however, newly accumulated data provide a more detailed history for most of them, especially as they relate to their producers. The Index will also provide histories for a few forgotten papers I’ve rediscovered.

The Index’s third phase will be the introduction of a search engine to connect the newspapers and their people to the places where they were produced. Doing this will provide a foundation for the final element of the “Index”: a bibliographical record for each imprint produced in Virginia through 1820.

Once complete, this online resource will allow researchers to better situate all three components of the Virginia printing trade—people, places, and imprints—in their own investigations. It will also be easily updated, whether correcting inaccuracies or adding new entries. But most importantly, those researching Virginia’s early history will finally be able to end the ongoing reliance on the imperfect works of the “old masters.”

[Editor’s Note: This article previously appeared on the Readex Blog on October 1, 2012.]