“A Family Newspaper”: Pearl Rivers and the Rebirth of the New Orleans Daily Picayune

Though no one would have realized it at the time, October 17th 1866 was an auspicious date in the long history of the New Orleans Daily Picayune (founded in 1837). The city was recovering from Civil War: Federal troops still occupied the humbled “Queen of the South,” and political and racial tensions simmered, sometimes exploding into violence on the streets. In such a climate, the slight poem entitled “A Little Bunch of Roses” that appeared on the front page of the evening edition might have escaped the attention of some readers.

Click image to view pdf

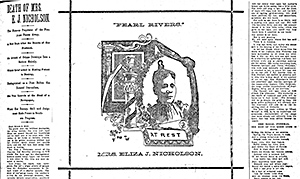

The paper even got the poet’s nom de plume wrong, attributing it to “Pearl River” instead of “Pearl Rivers.” But however unheralded, this would prove to be the first appearance in the pages of the Picayune of a young woman who would go on to have an extraordinary influence on its development. Before too many years had passed, Pearl Rivers—really Eliza Jane Poitevent—would be the first woman to run a daily metropolitan newspaper in the United States. Her extraordinary achievements can be traced through the digitized pages of the Picayune in America’s Historical Newspapers.

The route from “A Little Bunch of Roses” to the proprietorship of the Picayune was a circuitous one: born and raised in Mississippi, Pearl Rivers’ literary ambitions drove her (against her family’s wishes) to take up residence in New Orleans at the house of her maternal grandfather in the late 1860s. His connections put her in contact with a number of significant New Orleanians, including Alva Morris Holbrook, then owner of the Picayune. In 1870, Holbrook hired Pearl as the paper’s literary editor, making her the first professional female journalist in New Orleans. In 1872, the pair were married. The union was turbulent—not least because Holbrook’s first wife attempted to murder Pearl—and short: Holbrook died in 1876. Although he left his wife ownership of the New Orleans Picayune, a variety of bad business decisions in the preceding years, exacerbated by the political and economic climate of the city, meant that he also left the paper saddled with roughly $100,000 of debt. Ignoring the many voices who advised her to declare bankruptcy, Pearl Rivers instead set about revivifying the Picayune.

Click image to view pdf

Tellingly, in a statement published on 26 March 1876 apprising readers that the paper was under new management, Pearl declared the Picayune to be both "a Southern newspaper" and "a family newspaper" which would "devote its columns to the discussion of all the leading questions of public interest and publication of the latest intelligence from the several departments of literature, science, politics and trade." Certainly, it was the families of New Orleans—and not just the patres familias—that Pearl Rivers targeted in her attempts to save the Picayune. Through a series of popular innovations and inspired hirings she widely extended the paper’s appeal. In so doing, she tripled its circulation from 1880 to 1890.

Click image to view pdf

The first of her characteristic novelties was the introduction of a society column. When “The Buzzings of the Society Bee” first appeared on March 16th 1879, New Orleanians were introduced to “a gossipy little creature” who spread the news of parties, engagements and other assorted activities of the bon ton. Here, Pearl was emulating Northern newspapers, as she made clear in the inaugural column: “in all of our large Northern cities it has become [...] a part and parcel of every day existence," she argued, while also admitting, “We of the South have heretofore shut our ears to the buzzing of this lively insect [...] Southern Society would [have] none of it, and made a struggle to keep its dresses and diversions out of the local papers.” Local resistance to the Society Bee was forceful but short-lived; soon it had taken a central place in the social life of the city.

Click image to view pdf

Other new departments followed. “In Lilliput Land” was a section for the city’s children. Its first appearance on March 5th 1893 began with a typical entreaty to its young readers: “The editor of this column would like to know just how you treat your mother? Are you ever cross, or impatient, or even a little bit saucy with her?”

Click image to view pdf

When the weather-frog was introduced in 1894, he too was an immediate favorite with young and old. A debonair amphibian, “The Picayune’s Weather-Prophet” presented the daily forecast for decades, becoming an enduring symbol of the newspaper itself, and occasionally getting in the holiday spirit. On Valentine’s Day 1895, for example, he dressed as Cupid—while a verse warned, “Sweet maid have a care! Of Froggy beware!”

Click image to view pdf

Throughout her time at the Picayune, Pearl bolstered these kinds of pioneering developments with an ability to foster talent—particularly the talents of other literary women. When she introduced Dorothy Dix to the pages of the Picayune in the 1890s, she set in motion the career of one of the most successful newspaper columnists of the era. In later years, syndicated around the globe, Dix would be read by millions; but it was in the pages of the Picayune that she established her popularity. Offering advice on the pressing topics of the day—including those pertaining to marriage—Dix didn’t pull any punches when dispensing her wit and wisdom. In her “Dorothy Dix Talks” column of May 16th 1897, for example, she advised her readers to "refuse to marry a man who does not read the papers" in no uncertain terms: "He's a chump, girls. If he lives a thousand years there will never be any streets named after him. He's the kind of a man who makes a bright, progressive woman very, very tired."

Click image to view pdf

No less significant, at least to a local audience, were the writings of Catharine Cole. After her arrival at the paper in 1881 she travelled widely for the Picayune, filing reports from locations across America and Europe, and covering historic events like the 1893 Chicago World’s Fair with an eye for detail appreciated by her local readership. In her "Columbian Correspondence" for May 31st 1893, for example, she related her arrival in Chicago in terms that would have been appreciated at home: "the New Orleans passengers [...] huddled forlornly like shorn sheep in their unwise silks and insufficient linens [...] we all tried to look as we liked being cold and half frozen."

Letter #1

Click image to view pdf

Letter #2

Click image to view pdf

The work of these groundbreaking figures, Pearl Rivers chief among them, was instrumental in the transformation of the fortunes of the Picayune and its ongoing survival; at the same time, they also ensured that New Orleans would become a vital center for literary women. Elaine Showalter has even described the city "as the headquarters of the New Woman" in the late nineteenth century. But despite that, and despite their achievements in the face of some adversity, the women of the Picayune were never too radical in their rhetoric—something clearly demonstrated when Catharine Cole visited the Chicago World’s Fair in 1893. One of her duties was to represent the Picayune at the Press Congress. “I had the honour,” she wrote, “to represent the only woman in the world who is at the actual head of a great daily news journal.”

In a written address to the Congress, Pearl Rivers noted the irony that it was from “the so-called slow-going and conservative south” that a woman should be selected “to represent her sex in one of the most diligent and profound professions.” But she also asserted that "a woman and a newspaper is an incongruous combination." More, she proclaimed that the work of a "woman newspaper editor and proprietor" was in many ways "a perversion of her nature, the dying of a daily death." And so accordingly—to "a great big burst of applause," Cole noted—Pearl Rivers offered a statement in defense of her dual roles as businesswoman and mother: "I may say, truthfully, that although I may sometimes have neglected the business, I have never neglected the babies."

Click image to view pdf

Those words served as a modest and inadequate self-epitaph: three years later, Pearl Rivers was dead. Better tribute was paid by the Picayune itself: on February 16th 1896, the day after her death, Pearl’s obituary took over the entire black-bordered front page, and the paper’s praise for its saviour was fittingly fulsome: "The grandest reign in the history of England was that of Elizabeth [...] In some sort the administration of the Picayune by this lady has been like this." Her legacy at the Picayune, and in the wider cultural life of New Orleans, lives on.