Mr. Jefferson’s Mandarin, Or, a controversial promotion

When the ship Beaver departed New York harbor bound for the China coast in August 1808, the United States was fully embargoed. For over six months the country’s trade had been at a standstill, and all the ports idled. The livelihoods of America’s maritime workers had been sacrificed to the greater good by Jeffersonian Republicans, in the White House and the Congress, who hoped that an extreme form of commercial warfare—a wholesale ban on international trade—would force Great Britain and France to respect American neutrality without any shots fired.[1]

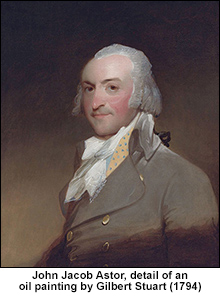

Though it sailed out as an exception to the embargo, the Beaver was no smuggler, and its owner, fur trade magnate John Jacob Astor, was no scofflaw—not this time, at least. The ship was one of the few granted official permission to sail beyond coastal waters—and in this case, that grant came from the President himself, Thomas Jefferson. How did the Beaver and Astor manage this good fortune, one that all the merchants and sailors in America languishing under the embargo desperately desired? The answer lies in the Beaver’s most important passenger: “Jefferson’s mandarin,” a man named Punqua Wingchong.[2]

Punqua had traveled to Washington in mid-July 1808 to “sollict the means of departure…to China” directly from President Jefferson. Though accompanied by a translator and a letter of introduction from New York Senator Samuel L. Mitchill, Punqua was never able to meet with the President; the sage had once again retired to Monticello before he could get an audience. But in the end, that didn’t matter. Once Jefferson heard of his case he gave Punqua permission to hire a ship to return to his home port of Canton, China. Jefferson considered this to be more than an act of kindness to a stranger far from home—it was a piece of diplomacy, an act, he explained in a letter to Albert Gallatin, his Secretary of the Treasury, of “national comity” that could serve as a “means of making our nation known advantageously at the source of power in China.”[3]

This evaluation of the exception given to Punqua, and subsequently, to his transport, the Beaver, was not widely shared. Indeed, the question of just who—or what—the Chinese visitor actually was formed the basis for a new form of critique of the Jefferson administration’s handling of the embargo. The controversy played out for months in the nation’s vigorous partisan and commercial press—the two sectors virtually indistinguishable on the charged question of the embargo—and can be followed quite clearly in America’s Historical Newspapers.

The terms used to refer to Punqua lay at the crux of the matter: was he a mere shopkeeper, an important merchant, or a powerful mandarin? In his letter of introduction, Senator Samuel L. Mitchill proclaimed Punqua a “Chinese merchant,” a term that implied both means and gravitas—but no diplomatic status. Secretary of the Treasury Gallatin used the same construction in his orders authorizing the Port of New York to allow the Beaver’s voyage to proceed.[4] Jefferson, however, promoted Punqua, naming him a “mandarin”—an official of the Qing Empire. It was the exalted rank bestowed by Jefferson that public supporters and critics alike picked up on when the Beaver’s voyage became more widely known.

The news did not take long to spread. On August 4, 1808, just one day after the administration moved to allow the voyage, a notice appeared in the New-York Evening Post reporting that one of John Jacob Astor’s ships would carry “the Mandarin Chief and his Secretary” back to China. The news not only made the rounds of the New York commercial and political newspapers, it also appeared in papers up and down the East coast and even into the Appalachian interior, a testament either to how starved the country was for maritime intelligence, or how remarkable Punqua and the Beaver were seen to be.[5]

The Beaver’s departure entered the realm of public controversy in New York a little over a week after the first reports, through an editorial in the Commercial Advertiser. Making private whispers into public business, the Advertiser’s editors declared it was “well known” that Punqua “is no Mandarin” and further, was “not even a licensed or security Merchant.” In fact, “his departure from China was contrary to the laws of that country”—emigration was forbidden by the Qing—and so on arrival in China Punqua would have to be smuggled in, “put on shore privately”; only “the obscurity of his condition in life, affords him the only chance he has of avoiding punishment.” The danger Punqua faced was less dear to the hearts of New York’s merchants, though, than the reason for the dissimulation: the Beaver’s owner, the Advertiser alleged, “has offered to contract for bringing home goods on freight.” The whole voyage, the editors concluded, was a scam, a ruse Astor was using to evade the embargo with government permission.[6]

Similarly upset at the evident unfairness of allowing Astor’s ship to leave while their vessels rotted at anchor, a group of Philadelphia merchants wrote Secretary Gallatin privately to inform him that Punqua was “an imposter”; some of the merchants knew him as a “petty shopkeeper in Canton, utterly incapable of giving a credit.” [7] A pseudonymous letter forwarded to Gallatin echoed these charges, and more. Going beyond the profit motive, Gallatin’s informant claimed there was a political spin to the fraud: the Beaver belonged to “the bitterest opposers of the present administration” who were using “their tool Winchong” to catch windfall profits while making a mockery of the capstone policy of Jefferson’s second administration.[8]

Punqua stayed silent in the face of these accusations, but both Astor and Gallatin disclaimed any fraud, corruption, or misrepresentation.[9] Replying to the anonymous tipster in the Commercial Advertiser, Astor called his accusers’ bluff, offering to present “a statement of facts” to whomever had leaked the story, which would, he said “relieve him from the anxiety under which he appears to labor for the honor of the government, and the reputation of all concerned.” [10] No further reports on the matter were forthcoming from the Advertiser.[11]

Gallatin made no excuses for the President’s decision, but he did not entirely support it, either. He explained to merchants who complained that the Beaver’s permit was issued with the same restrictions that affected any other vessel leaving during the embargo. If the ship’s owners brought back property beyond what was allowed “their bond will be forfeited,” just as any other. Further, Gallatin maintained that the administration had been perfectly within its rights to approve the new voyage, regardless of Punqua’s status.[12] But implicit in his message was a sense that the Secretary had been overruled by Jefferson, as part of the President’s fanciful interest in improving relations with China.

Interestingly, charges and countercharges about Punqua’s true identity continued long beyond the official responses. The pro-administration Monitor, arguing that the “scandalous stories circulating in the opposition” were in error, responded with an intense defense of Punqua’s status, couched in terms that reveal much about what the American public thought about Chinese society. The “elegance of his penmanship,” the Monitor declared, revealed that he was “no mean scholar”—and as “learning in China is the best recommendation to preferment in the offices of state,” the editors regarded this as “incidental proof of his being a Mandarin.” His “sufficient knowledge of the English tongue” was in his favor, too, as was his “deportment,” which was “that of a respectable personage.” His physical otherness also worked in his defense, forbidding any “suspicion of his being a European or an American”: “the features of the man,” the editors explained, “are sufficient to convince any one that he is no imposter.” Attacks on his legitimacy were partisan rudeness, the Monitor concluded, “a disgusting specimen of American indecorum; which we hope never again to witness with respect to any foreigner who demeans himself with propriety.”[13]

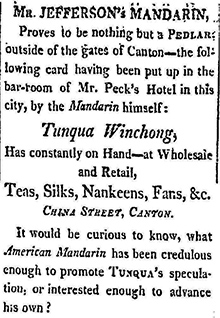

Unsurprisingly, testimony of elegant penmanship expressed through condescending rhetoric did nothing to quiet rumors. A few weeks later in Baltimore, the North American reported that evidence that “JEFFERSON’S MANDARIN” was “nothing but a PEDLAR” had been discovered in a hotel barroom—to wit, a business card advertising Punqua’s shop on China Street, Canton. With this new evidence, the editors wondered “what American Mandarin has been credulous enough to promote TUNQUA’s speculation; or interested enough to advance his own?” [14] Astor’s alleged duplicity was, once again, at the heart of the controversy.

Perhaps unintentionally, the North American appears to have gotten the facts correct; Punqua appears to have been neither a wealthy Canton merchant, nor a highly placed mandarin, but rather a well-traveled shopkeeper. [15] As one of the many small-time entrepreneurs working outside Canton’s walls, he likely lacked official permission from the Qing government to trade with Westerners. Instead he dealt with them in one of the many cramped shops in the chaotic side streets that subdivided the foreign quarter of Canton—Thirteen Factory Street, Hog Lane, or, indeed, China Street.[16]

The reasons for his voyage to the U.S. are not entirely clear: correspondence within the Jefferson administration suggests that he had come to America “for the purpose of collecting debts due to his Father’s Estate.” [17] Chinese merchants did indeed pursue debt collections in the United States, occasionally using proxies to sue in U.S. courts; but Punqua presents the unique case of pursuing his business in person.[18] Perhaps the size of his operations made an attempt at in-person collection the more economical decision, or perhaps he was simply curious to see more of the world. In either case, it seems unlikely that Punqua was Astor’s puppet; but if his goals were compatible with Astor’s, it seems logical to conclude the Beaver’s voyage was the result of a coincidental union of interests.

Jefferson’s confidence in Punqua’s diplomatic importance notwithstanding, the entire affair was an embarrassment—not least to Gallatin, whose efforts to impose some sort of system on the embargo were increasingly made in vain. One of the more striking ironies of Jefferson’s first term was that the leader of the party that championed small government had overseen the doubling of the nation’s size. His administration’s perplexing efforts to rigidly control Americans’ economic activity made his second term no less ironic, at least with regard to its stated principles. Seen in this light, Punqua’s voyage home—and the Beaver’s lucrative return to New York—stand together as perhaps the best coda to what Jefferson’s Federalist opponents had labeled his “Chinese policy” of embargo.[19]

Footnotes

[1] For evaluations of the embargo’s effectiveness—and particularly the growth in federal administrative apparatus it engendered—see Leonard Dupee White, The Jeffersonians: a Study in Administrative History, 1801-1829 (New York: Macmillan, 1951), 423–74; Burton Spivak, Jefferson’s English Crisis: Commerce, Embargo, and the Republican Revolution (Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1979), 102–225; and Jerry L. Mashaw, “Reluctant Nationalists: Federal Administration and Administrative Law in the Republican Era, 1801-1829,” The Yale Law Journal 116, no. 8 (June 1, 2007): 1636–1740.

[2] For the term used for Punqua, see: “Mr. JEFFERSON’S MANDARIN,” North American (Baltimore, MD), 2 September 1808.

As is common with Chinese names transliterated into English, particularly during this period, the spelling of Punqua’s name varies a great deal from writer to writer. I have here followed the convention of most writers on the matter in using “Punqua Wingchong” —partly for easy comparison but also because there is a chance that this is how Punqua himself may have written his name in English. The evidence for the latter point comes from a series of advertisements that ran in New York and Boston commercial papers in the fall of 1811, inviting American China traders to visit Punqua’s new silk shop on China Street, in the foreign quarter at Canton. In the absence of clearer evidence of writing by Punqua’s direction or by his own hand, using the spelling found in these advertisements seems the best alternative. See: “New Silk Store,” Columbian Centinel (Boston, MA), 7 September 1811 (reprinted in: New-York Gazette, 31 Oct 1811)

[3] Punqua’s translator was Aaron Palmer, of New York. See: Samuel Latham Mitchill to Thomas Jefferson, July 12, 1808, reprinted in Kenneth Wiggins Porter, John Jacob Astor, Business Man, 2 vols., Harvard Studies in Business History (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1931), 1:420-421; Thomas Jefferson to Albert Gallatin, Monticello, 25 July 1808 in Porter, John Jacob Astor, Business Man, 1: 421–423.

[4] Samuel Latham Mitchill to Thomas Jefferson, July 12, 1808 and Albert Gallatin to David Gelston, Treasury Department, 3 August 1808 in Porter, John Jacob Astor, Business Man, 1:420-424.

[5] The notice appeared in the N-YEP’s editorial column, and was quite brief—perhaps helping it spread quickly: “We understand that the ship Beaver, belonging to John J. Astor, of this city, has got permission to take out to China, the Mandarin Chief and his Secretary, who have been detained in this country ever since the Embargo was laid,” New-York Evening Post, 4 August 1808; it was reprinted in the Mercantile Advertiser (New York), 5 August 1808; L'Oracle and Daily Advertiser (New York), 5 August 1808; New York Herald, 6 August 1808; Alexandria Daily Gazette, Commercial & Political (Alexandria, VA), 8 August 1808; North American and Mercantile Daily Advertiser (Baltimore, MD), 8 August 1808; Republican Watch-Tower (New York, NY), 9 August 1808; Norwich Courier (Norwich, CT), 10 August 1808; Universal Gazette (Washington, DC), 11 August 1808; Albany Register (Albany, NY), 12 August 1808; Farmer's Repository (Charlestown, VA – now WV), 12 August 1808; Norfolk Gazette and Publick Ledger (Norfolk, VA), 12 August 1808; Democrat (Boston, MA), 13 August 1808; Charleston Courier (Charleston, SC), 15 August 1808; Republican Star (Easton, MD), 16 August 1808; Olive Branch (Norwich, NY), 20 August 1808; Columbian Gazette (Utica, NY), 23 August 1808. Other notices of the Beaver’s departure include: "The ship Beaver," Repertory (Boston, MA), 9 August 1808, reprinted in the Connecticut Journal (New Haven, CT), 11 August 1808 and Political Censor (Staunton, VA), 24 August 1808.

Surprisingly, in light of the voyage’s subsequent notoriety, this first news of it does not seem to have attracted much published comment, at least at first. Only the editors of the New-England Palladium (a Federalist war horse) ventured a bit of dry wit, declaring that the venture offered “[a] good chance for the owner of the ship,” a decided understatement given that the Astor would have an effective monopoly on the sale of China goods upon the Beaver’s return to the U.S.—and everyone knew it. See: “The ship Beaver,” New-England Palladium (Boston, MA), 9 August 1808.

[6] “The Ship Beaver and the Mandarin,” Commercial Advertiser (New York), 13 August 1808.

[7] William Jones, et al. to Albert Gallatin, Philadelphia, 10 August 1808 in Porter, John Jacob Astor, Business Man, 1:424–425.

[8] "Columbus" to James Madison, Boston, 11 August 1808 in Albert Gallatin Papers, New-York Historical Society, reel 6.

This letter was first brought to light and analyzed in John Kuo Wei Tchen New York Before Chinatown: Orientalism and the Shaping of American Culture, 1776-1882 (Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1999), 43, 313 n. 4.

[9] Interestingly, the other merchants involved in the Beaver’s voyage, the firm of James &Thomas Handasyd Perkins, were not mentioned in the press, nor did they offer any public comment—though they sold their share of the Beaver’s return cargo for $113,000 in July 1809. This is somewhat striking given that the Perkins brothers were otherwise active opponents of the Jefferson administration, and played a significant supporting role in the Federalist politics of New England. See: Carl Seaburg and Stanley Paterson, Merchant Prince of Boston: Colonel T. H. Perkins, 1764-1854 (Cambridge Mass: Harvard University Press, 1971), 198, et passim.

[10] “To the Editor of the Commercial Advertiser,” Commercial Advertiser (New York), 15 August 1808.

[11] Oddly, Astor does not seem to have held a grudge—when the Beaver returned to New York in early June 1809, he announced the sale of goods from the ship in the Advertiser. For Astor’s advertisements, see: “For sale by J. J. Astor...,” Commercial Advertiser (New York), 6 July 1809 and "For sale by J. J. Astor..." New-York Gazette, 29 June 1809.

In a passage many later writers reference, Albion reports that the Beaver’sprofits were in the neighborhood of $200,000—though he does not specify a source for the figure, nor how the money was shared between the different merchants invested in the property on the ship; that said, even if just counted as Astor’s personal profits, the figure is not beyond the realm of possibility. See: Robert Greenhalgh Albion, The Rise of New York Port, 1815-1860 (New York: C. Scribner’s Sons, 1939), 197.

[12] Albert Gallatin to Capt. William Jones, Treasury Department, 17 August 1808 in Porter, John Jacob Astor, Business Man, 1:426–428.

[13] “The candid reader...” The Monitor (Washington, DC), 20 August 1808; Reprinted in: L'Oracle and Daily Advertiser (New York), 24 August 1808. Reports summarizing the Monitor’s argument also appeared in a few places: "The name of the Mandarin..." Mercantile Advertiser (New York), 24 August 1808; reprinted in Alexandria Gazette (Alexandria, VA), 27 August 1808.

The battle continued even longer, too. An influential account published decades after the incident pushed even further, declaring Punqua to be but “a common Chinese dock loafer” that Astor had “picked up…in the Park” and dressed up in a mandarin’s costume in order to evade the embargo. Joseph Alfred Scoville, The Old Merchants of New York City by Walter Barrett, Clerk, 5 vols. (New York: Thomas R. Knox & Co., 1885), 3:8.

[14] “Mr. JEFFERSON’S MANDARIN,” North American (Baltimore, MD), 2 September 1808. The story was reprinted in the New-York Evening Post, originator of the controversy. See: "Mr. Jefferson's Mandarin," New-York Evening Post, 5 September 1808.

[15] At least, detractors’ claims that Punqua was just such are supported by evidence generated during what appears to be a later trip to the United States to promote this same shopkeeping business. Indeed, it seems likely that Punqua visited the U.S. multiple times: in 1808, then again in 1811, when advertisements for his Canton shop appeared, and finally once more in 1818, when his presence was noted in published passenger lists and mail calls. Several times, he was recognized (or thought to have been recognized) from his appearance in the 1808 contretemps; and his travels noted in the press as he visited the major cities of the East coast. See: “New Silk Store,” Columbian Centinel (Boston, MA), 7 September 1811 (reprinted in: New-York Gazette, 31 Oct 1811); "Shipping Intelligence. Port of Boston...Monday, Jan 19" Boston Daily Advertiser, 20 January 1818 (reprinted in: New-York Gazette, 23 January 1818); "Lang, Turner & Co's Marine List," New-York Gazette, 9 March 1818; New-York Evening Post, 25 March 1818; "List of Letters, Remaining in the Post Office on the 1st of May, 1816," National Advocate (New York), 8 May 1818.

[16] For details on the geography of the foreign quarter, and Americans’ experience of street life there, see: Jacques M. Downs, The Golden Ghetto: The American Commercial Community at Canton and the Shaping of American China Policy, 1784-1844 (Bethlehem, PA: Lehigh University Press, 1997), 25–36.

[17] Albert Gallatin to David Gelston, Treasury Department, 3 August 1808 in Porter, John Jacob Astor, Business Man, 1:423; "Columbus" to James Madison, Boston, 11 August 1808 in Albert Gallatin Papers, New-York Historical Society, reel 6.

The writer of the pseudonymous letter sent to Madison and forwarded to Gallitin suggested that these debts were owed to Punqua by Samuel Shaw and Thomas Randall, merchants who had served as supercargoes on the first American voyage to China, and later as the nation’s first officials (consul and vice-consul, respectively) in Canton.

For his part, Winchong was quite courteous. After his return to China he sent the Madisons (James and Dolly) a gift through Jesse Waln, a Philadelphia merchant; he had perhaps encountered the couple while visiting Washington in search of Jefferson in 1808. See: Jesse Waln to James Madison, Philadelphia, 23 April 1810 in James Madison, The Papers of James Madison: Presidential Series, ed. Robert Allen Rutland et al. (Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1984), 2:322–323.

[18] On hong merchants bringing suit in the U.S., see Frederic Delano Grant, “Hong Merchant Litigation in the American Courts,” Proceedings of the Massachusetts Historical Society 99 (1988): 44–62. For Conseequa’s letter, see: “Conseequa vs. Willing & Francis” Willings and Francis Records, (Collection 1874), Folders 1-8, Historical Society of Pennsylvania; Conseequa (or Ponseequa), Petition to the President (Madison), 10 February 1814, in M101: Despatches from U.S. Consuls in Canton, China 1790-1906, RG 59: General Records of the Department of State (Washington, D.C.: National Archives, 1964), reel 1; Lo-shu Fu, tran., A Documentary Chronicle of Sino-Western Relations, 1644-1820 (Tucson: Published for the Association for Asian Studies by the University of Arizona Press, 1966), 1:391–393.

[19] For a succinct view of Jefferson’s opinion of this accusation, see: Thomas Jefferson, The Writings of Thomas Jefferson, ed. Andrew Adgate Lipscomb, Albert Ellery Bergh, and Richard Holland Johnston, 20 vols. (Washington, D. C.: Issued under the auspices of the Thomas Jefferson memorial association of the United States, 1903), 12:235–238, esp 237–238. On the Beaver’s voyage, see: "Marine List," Commercial Advertiser (New York), 8 June 1809; for a detailed account of the ship’s return voyage (115 days from Canton, returning via the Cape of Good Hope route, carrying a classic cargo of teas, nankeens, and chinaware), including a description of its encounters with British cruisers, see: "Ship News," Democratic Press (Philadelphia, PA), 13 June 1809.