“Bustle in the House of Wisdom:” The Life and Crimes of Vermont Congressman Matthew Lyon

Multiple choice: You’re Matthew Lyon, a member of the U.S. House of Representatives in 1801. On the occasion of your fifty-second birthday, you’re asked what your most enduring legacy will be, that for which you’ll be remembered in two hundred years. Which of the following answers do you choose?

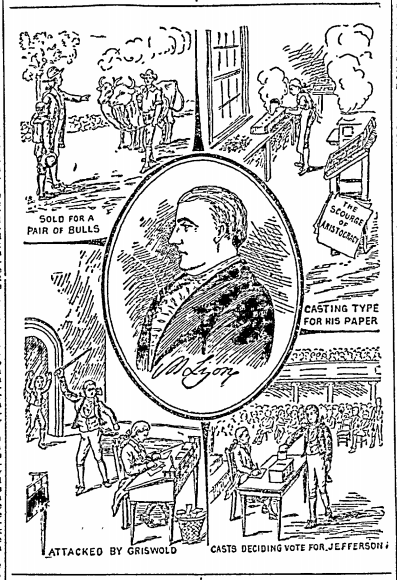

- You were the first person convicted for violating the Sedition Act of 1798, when you accused President John Adams in print of “ridiculous pomp,” among other things.

- You were the first (and only) member of Congress to be reelected while imprisoned (for the above infraction).

- You were the first member of Congress charged with “gross indecency” and were repeatedly threatened with expulsion from office, for spitting in the face of a fellow member of Congress, and for the physical violence that ensued.

- You cast the deciding Congressional vote to elect Thomas Jefferson as President during the Election of 1800

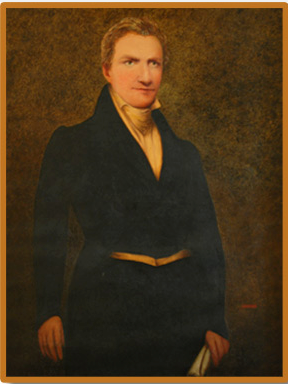

With perfect hindsight from the twenty-first century, the election of Thomas Jefferson looms large in the list above, but all of these choices are notable for their impact on the course of early American history. Matthew Lyon was an Irish immigrant, an entrepreneur, and an (allegedly) disgraced Revolutionary War officer who served with Ethan Allen’s Green Mountain Boys. Lyon was a vehement anti-Federalist. The Federalists believed in a strong central government, whereas Lyon and his fellow Democratic-Republicans feared monarchy and favored states’ rights instead.

Beyond his particular views, however, Lyon was an iconoclast, a newspaper publisher who pulled no punches. He founded the town of Fair Haven, Vermont, and later moved to Kentucky in search of farmland and political refuge. He died in Arkansas Territory in 1822. He is now the subject of a musical, Spit’n Lyon, composed in the vein of the Broadway smash, Hamilton. And he comes alive in such Readex Archive of Americana collections as American State Papers, American Pamphlets, Early American Imprints, Early American Newspapers and several others.

Matthew Lyon came to America in 1765 when he was in his teens. He worked as an indentured servant first in Connecticut and then in Vermont, paying off the cost of his passage in four years. In the Revolutionary War he organized a company of militia, participated in the capture of Fort Ticonderoga with the Green Mountain Boys, fought at Saratoga and Bennington, and finished his service with the rank of colonel. Following the war he settled in Vermont and established various businesses, among them a sawmill, a paper mill, a foundry, and several newspapers.

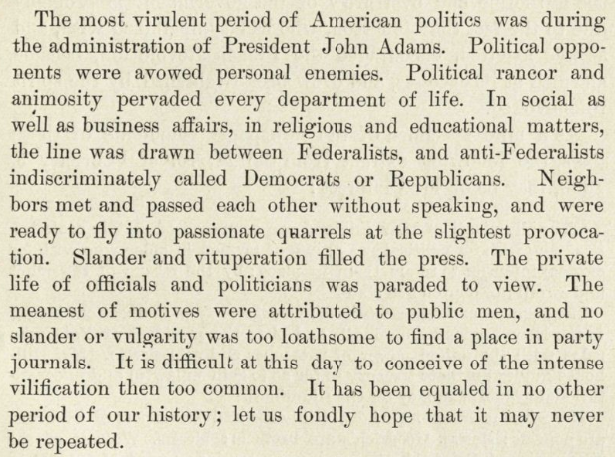

Lyon was first elected to Congress in 1797 after serving in the Vermont State Legislature from 1779 to 1796. This was a time in American politics when parties were still being defined. As a Democratic-Republican, Lyon was aligned with Thomas Jefferson. The opposing Federalist Party was led by President John Adams and Alexander Hamilton. In a pamphlet from the New-York Historical Society, published in 1900 and found in Readex’s America’s Historical Imprints, the author described that tumultuous period in words that may sound very contemporary:

The most virulent period of American politics was during the administration of President John Adams. Political opponents were avowed personal enemies. Political rancor and animosity pervaded every department of life. In social as well as business affairs, in religious and educational matters, the line was drawn between Federalists, and anti-Federalists, indiscriminately called Democrats or Republicans. Neighbors met and passed each other without speaking, and were ready to fly into passionate quarrels at the slightest provocation. Slander and vituperation filled the press. The private life of officials and politicians was paraded to view. The meanest of motives were attributed to public men, and no slander or vulgarity was too loathsome to find a place in party journals. It is difficult at this day to conceive of the intense vilification then too common. It has been equaled in no other period of our history; let us fondly hope that it may never be repeated.

In evidence of this animosity, the same pamphlet includes a satirical notice heralding “The Lyon of Vermont” as he embarked upon his first U.S. Congressional term in 1797. The writer, William Cobbett, alias Peter Porcupine, was a conservative Anglophile publisher who objected to Lyon’s coolness towards Great Britain.

To-morrow morning at eleven o’clock will be exposed to view the Lyon of Vermont. This singular animal is said to have been caught in the bog of Hibernia, and when a whelp transported in America; curiosity induced a New Yorker to buy him, and moving into the country afterwards exchanged him for a yoke of young bulls with a Vermontese. He was petted in the neighborhood of Governor Chittenden and soon became so domesticated that a daughter of his excellency would stroke and play with him as a monkey.

Lyon’s tenure in the House was fraught with controversy. From the first he refused to conform to precedent, even in such benign gestures as a ceremonial visit to President Adams:

Lyon then got the floor, and stated his grievance, which was the old one of the session before. In substance he said: As I rose the first time, my purpose was to move a committee to carry the address. But I will restrain myself. I will not deprive members of the pleasure they feel when indulged with pageants and street parades. A like consideration surely will be given to my feelings, and leave granted me to remain in the House till the members return.

That political tension took on a more serious tone as the factions began taking sides over the Quasi-War with France (1798-1800). This was a conflict that derived from the United States reneging on its debts with France following the French Revolution, on the basis that those obligations were owed to a regime which no longer existed. The French began attacking American ships, and the U.S. Navy responded in kind, ruining France’s East India trade. Britain, about to embark upon the Napoleonic Wars, was keen to side with America against her historical nemesis.

Political loyalties in America were split between those seeking security with Great Britain and those in favor of negotiating with the nascent French Republic. This polarization came to a head during the first impeachment proceedings ever undertaken by the U.S. Congress, against Senator William Blount of Tennessee. Blount was accused of conspiring with Great Britain to seize the Spanish territory of West Florida to aid his land schemes.

During a break in those proceedings, Lyon was chatting with fellow House members in a provocative way when the conversation turned to Connecticut, then represented by the Federalist Roger Griswold, among others. Lyon asserted that Connecticut’s congressmen were slighting the interests of their constituents for political gain, and that if he were to establish a press in that state, he could turn the Federalists there out of office.

Naturally, Griswold did not agree, and alluded to an episode during the Revolutionary War when Lyon had allegedly been dishonorably discharged in a ceremony featuring the indignity of a wooden sword.

The mock-epic poem, “The House of Wisdom in a Bustle,” from Early American Imprints, Series I, describes what came next:

He turn’d up his eyes, his visage look’d horrid,

Sometimes it was pale, sometimes it was florid,

He look’d all convuls’d, and inwardly mutter’d

Some curses no doubt, but a word never utter’d,

Kept working his jaws as if he were chewing,

Which plainly denoted a something was brewing;

Stand aloof if you’re wise,--his senses are roaming,

My God! how he stares! how his mouth is a foaming!

He advances, behold! without saying the least word,

And spits in the face, of his foe from the eastward!!!

This, of course, was monstrous conduct for a House member, and would customarily lead to a duel. But it did not immediately provoke a violent response from Griswold, or even result in Lyon’s censure or expulsion from the House; the vote split on party lines, and did not reach a two-thirds majority.

Griswold would yet have his due, however; several weeks later he approached Lyon from behind while the latter was writing at his desk, and proceeded to beat him about the head with a stout walking stick. Lyon very much got the worst of the abuse as he attempted to rise to his feet and escape. When he seized a pair of tongs from the hearth the two adversaries came to grips and fell to the floor, only to be separated by the more temperate members of the House.

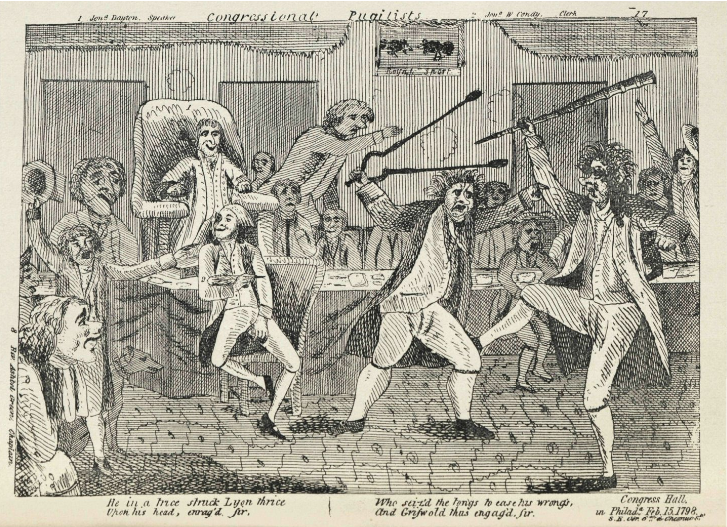

Here’s the famous etching of the “Congressional Pugilists” from American Pamphlets:

He in a trice, struck Lyon thrice

Upon his head, enrag’d sir.

Who seiz’d the tongs to ease his wrongs,

And Griswold thus engag’d, sir.

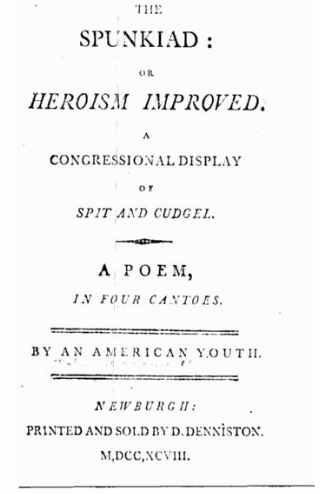

“The house of wisdom in a bustle,” indeed! The popular imagination was captivated through such renderings of the battle as “The Spunkiad: or Heroism Improved. A Congressional Display of Spit and Cudgel,” which can be found in Readex’s Early American Imprints:

Our Lyon now, astonish’d and perplex’d,

To find himself thus beaten, bruis’d and vex’d,

Was forc’d at present to endure his fate,

Yet vow’d to crush the coward soon or late.

Fortune ere long revers’d the former scene,

And wink’d to Lyon to emit his spleen;

Our injur’d wight the pressing moment caught,

And brac’d the arm which ne’er in vain had wro’t,

But Griswold, ere the thundr’ing storm began,

Escap’d the field and from the battle ran;

Till some humane, some sympathizing hand,

Convey’d a weapon to his flying friend:

But now, alas the thundering Speaker bawl’d,

And order soon from ev’ry side was call’d;

Our order-loving Dayton, sore afraid,

To see his darling get a broken head,

Soon found a way to check the gath’ring storm,

And screen his Griswold from impending harm.

When much debate on ev’ry side had past,

They came to this conclusive point at last;

That they no more their country should disgrace,

But FIGHT IT OUT, some other time and place!

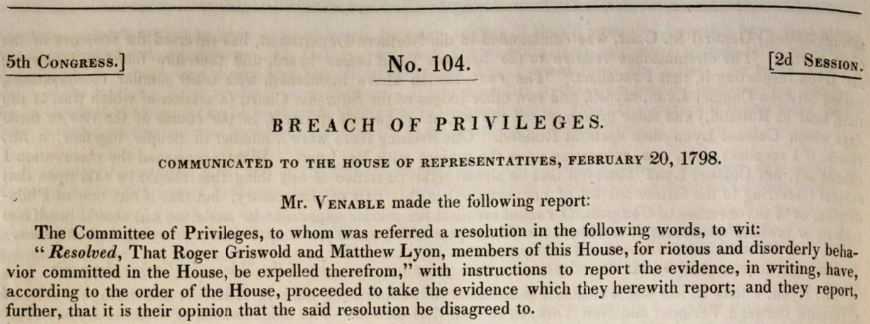

Once again, the two adversaries escaped reprimand or removal from office, though not for lack of effort on the part of the House:

The Committee of Privileges, to whom was referred a resolution in the following words, to wit: “Resolved, That Roger Griswold and Matthew Lyon, members of this House, for riotous and disorderly behavior committed in the House, be expelled therefrom,” with instructions to report the evidence, in writing, have, according to the order of the House, proceeded to take the evidence which they herewith report; and they report, further, that it is their opinion that the said resolution be disagreed to.

The several affrays on the House floor by no means diminished Lyon’s taste for notoriety. In print and in person he continued speaking his mind, whatever the cost. Later in 1798 the cost of running afoul of the executive branch was ratcheted up when President Adams signed the Sedition Act on July 14, 1798.

The Sedition Act was intended to quell dissent of the central government at a time when war with France was contemplated. It had distinctly unconstitutional overtones for the First Amendment’s guarantees of freedom of speech and freedom of the press, so much so that it was not renewed when it expired in 1800. For the Federalists, Lyon presented such a good opportunity for the law’s application that he was arrested under it for statements he had made before it was even enacted.

Matthew Lyon, while the Sedition Bill was on its passage through the House, wrote and dispatched a letter which, after Adams signed the bill, was read by the subscribers to the Vermont Gazette. The letter was no worse than those hundreds of honest gentlemen were constantly exchanging through the mails or intrusting for delivery to the care of private hands; no worse than Jefferson’s letter to Mazzei, than Adams’s letter to Tench Coxe, than the yet more famous letter in which, two years later, while the Sedition Law was still in force, Hamilton maligned Adams. But Lyon had long been a marked man. His conduct in the House, his fracas with Griswold, his hatred of idle show, had made him many enemies, and his enemies now took their revenge. He was no sooner at home than he was arrested for libel on three counts.

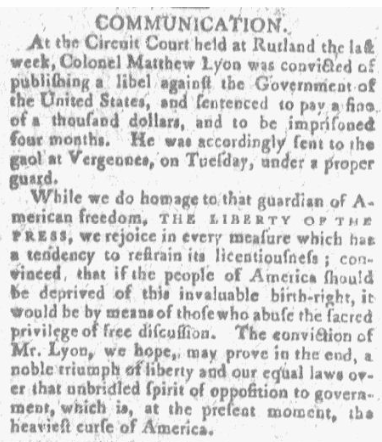

Here’s the notice of Lyon’s conviction in Spooner's Vermont Journal, published in Windsor, Vermont:

At the Circuit Court held at Rutland the last week, Colonel Matthew Lyon was convicted of publishing a libel against the Government of the United States, and sentenced to pay a fine of a thousand dollars, and to be imprisoned four months. He was accordingly sent to the gaol at Vergennes, on Tuesday, under a proper guard.

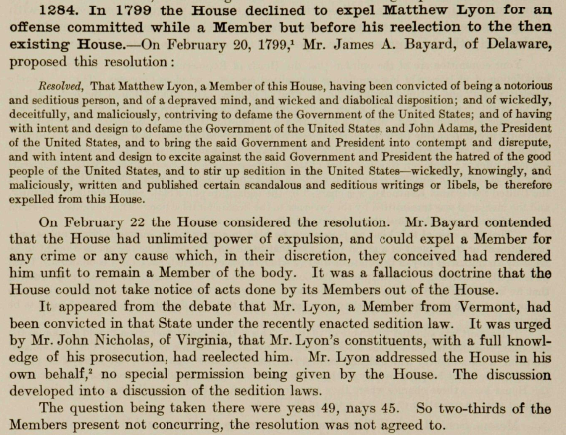

The wrath of Lyon’s enemies and his incarceration for four months in the jail at Vergennes didn’t at all dampen the ardor of his supporters as they elected him to another term in Congress. In Readex’s U.S. Congressional Serial Set we read how the House tried to expel him from that seat but could not muster the votes to do so.

On February 22 the House considered the resolution. Mr. Bayard contended that the House had unlimited power of expulsion, and could expel a Member for any crime or any cause which, in their discretion, they conceived had rendered him unfit to remain a Member of the body. It was a fallacious doctrine that the House could not take notice of acts done by its Members out of the House.

It appeared from the debate that Mr. Lyon, a Member from Vermont, had been convicted in that State under the recently enacted sedition law. It was urged by Mr. John Nicholas, of Virginia, that Mr. Lyon’s constituents, with a full knowledge of his prosecution, had reelected him. Mr. Lyon addressed the House in his own behalf, no special permission being given by the House. The discussion developed into a discussion of the sedition laws.

The question being taken there were yeas 49, nays 45. So two-thirds of the Members present not concurring, the resolution was not agreed to.

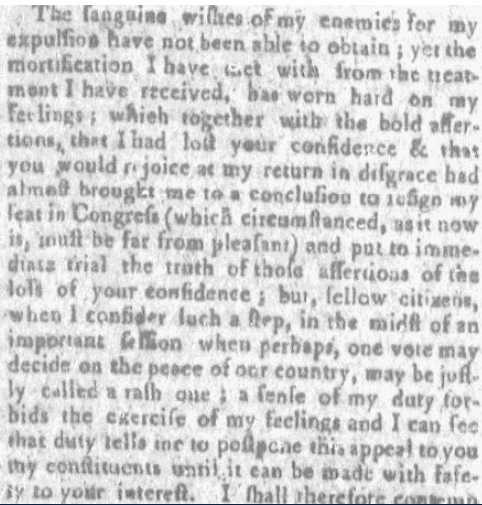

As much as we’ve heard about Lyon, we haven’t yet heard from him. In this passage, again from Spooner's Vermont Journal, Lyon speaks presciently of a time when the action of one man might make a profound difference in the fate of the republic.

The sanguine wishes of my enemies for my expulsion have not been able to obtain; yet the mortification I have met with from the treatment I have received, has worn hard on my feelings; which together with the bold assertions that I had lost your confidence & that you would rejoice at my return in disgrace had almost brought me to a conclusion to resign my seat in Congress (which circumstanced, as it now is, must be far from pleasant) and put to immediate trial the truth of those assertions of the loss of your confidence; but, fellow citizens, when I consider such a step, in the midst of an important session when perhaps, one vote may decide on the peace of our country, may justly be called a rash one; a sense of my duty forbids the exercise of my feelings and I can see that duty tells me to postpone this appeal to you my constituents until it can be made with safety to your interest.

And so it happened that the redoubtable Lyon was still in his seat when the Election of 1800 was thrown into the House for a decision. The Democratic-Republican ticket of Thomas Jefferson and Aaron Burr defeated the Federalist ticket of John Adams and Charles Pinckney in the general election, but at that time the positions of President and Vice-President respectively were also chosen by ballot. It turned out that Jefferson and Burr each got 73 electoral votes in their initial attempt.

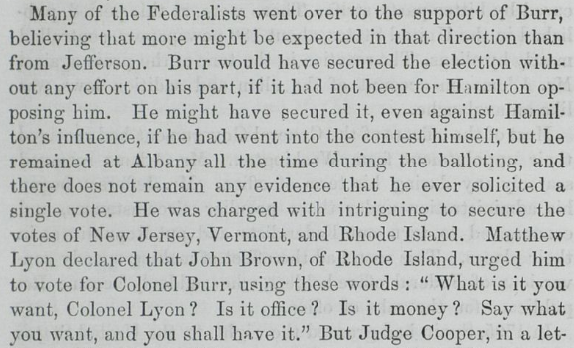

Today Burr is generally known as the person who killed Alexander Hamilton in a duel. That event, his subsequent flight from justice, and his ignominious political decline render his legacy unenviable to say the least. Yet he almost became president. Readex’s Afro-Americana Imprints gives us the play-by-play:

Many of the Federalists went over to the support of Burr, believing that more might be expected in that direction than from Jefferson. Burr would have secured the election without any effort on his part, if it had not been for Hamilton opposing him. He might have secured it, even against Hamilton’s influence, if he had went into the contest himself, but he remained at Albany all the time during the balloting, and there does not remain any evidence that he ever solicited a single vote. He was charged with intriguing to secure the votes of New Jersey, Vermont, and Rhode Island. Matthew Lyon declared that John Brown, of Rhode Island, urged him to vote for Colonel Burr, using these words: “What is you want, Colonel Lyon? Is it office? Is it money? Say what you want and you shall have it.”

The Platt pamphlet quoted in our introduction noted the political dissension during the administration of John Adams. Writing in 1900, Platt stated, “It is difficult at this day to conceive of the intense vilification then too common.”

Over a century hence, one manner in which we might more readily imagine the drama and peril confronting America during the Election of 1800 comes to us courtesy of Spit’n Lyon, the musical on Lyon’s life mentioned above. In their song, This Might Not Work, the composers offer a haunting, visceral setting for the dilemma facing the country—and especially the choice confronting Matthew Lyon—after thirty-five inconclusive ballots. Jefferson or Burr?

In the song, the composers refer to “Mr. Morris.” That would be Lewis Morris, Vermont’s other Congressional Representative, and a Federalist who initially voted for Burr. When he left his ballot blank on the thirty-sixth vote, Lyon voted for Jefferson, thus electing Jefferson President.

The song "This Might Not Work" from the musical Spit'n Lyon. Copyright © 2018 Spit'n Lyon. All Rights Reserved

This Might Not Work

16 states, majority stake,

Jefferson or Burr?

16 states, majority stake.

This might not work.

Electoral College with no return,

So it falls on Congress's shoulders.

Adams wasn't even close,

So they chose.

16 states, majority stake,

Jefferson or Burr?

16 states, majority stake.

This might not work.

Congress knew all too well.

Burr was on the VP ballot,

Choosing party over state,

Vote after vote tied eight to eight.

So it goes.

16 states, majority stake,

Jefferson or Burr?

16 states, majority stake.

This might not work.

The country is so young.

The power struggle, we’ll come undone.

In more danger by the hour,

Can we peacefully transfer power?

No one knows.

Mr. Morris, if you leave your ballot blank,

I'll leave Vermont.

There's no home for me anyway, for all the Adams magistrates.

Mr. Morris, have we reached an accord?

Let your handshake be your word.

16 states, majority stake,

Jefferson or Burr?

16 states, majority stake,

Jefferson.

We have a new President.

We have a new President.

We have a new President.

We have a new President.

Jefferson!

The title of the following government publication is so comprehensive in that regard that we hardly need delve into its contents:

Matthew Lyon cast the deciding vote which elected Thomas Jefferson President in 1801

Article showing that the vote cast by Matthew Lyon of Vermont, an Irish emigrant, was the deciding factor in the election of Thomas Jefferson as the third President of the United States in 1801.

Lyon’s legacy might be secure simply on his vote for Jefferson; like Hamilton, he favored principles over parties. Witness the equanimity with which Lyon considers reeling in the power of even his own party in the following exchange from The Vergennes Gazette and Vermont and New-York Advertiser:

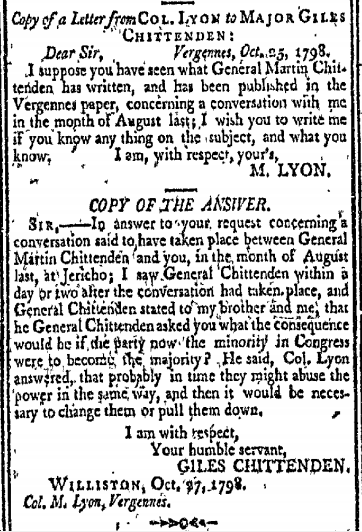

Copy of a letter from Col. Lyon to Major Giles Chittenden:

Vergennes, Oct. 25, 1798

Dear Sir,

I suppose you have seen what General Martin Chittenden has written, and has been published in the Vergennes paper, concerning a conversation with me in the month of August last; I wish you would write to me if you know any thing on the subject, and what you know;

I am, with respect, your’s

M. LYON

COPY OF THE ANSWER.

Sir,—In answer to your request concerning a conversation said to have taken place between General Martin Chittenden and you, in the month of August last, at Jericho; I saw General Chittenden within a day or two after the conversation had taken place, and General Chittenden stated to my brother and me, that he General Chittenden had asked you what the consequence would be if the party now in the minority in Congress were to become the majority? He said, Col. Lyon answered, that probably in time they might abuse the power in the same way, and then it would be necessary to change them or pull them down.

I am with respect,

Your humble servant,

GILES CHITTENDEN

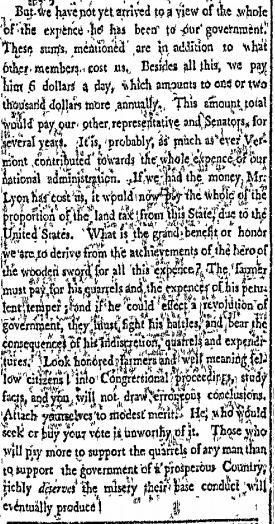

In fairness to Lyon’s detractors, he could become devoted to his strongly held opinions to the point of diminishing returns, or in the passage below, to the point of causing an excessive escalation in the cost of government. In this newspaper article, the unnamed author first tallies up the real costs of Lyon’s contested elections, the work of resolving the Griswold affair, all the ancillary printing and mailing of reports, and all the general bureaucratic business attributed to Lyon’s combative nature, and arrives at a total of about $100,000. Then he lays that sum at the feet of those who are taxed to pay for it:

But we have not yet arrived to a view of the whole of the expence to our government. These sums mentioned are in addition to what other members cost us. Besides all this, we pay him 6 dollars a day, which amounts to one or two thousand dollars more annually. This amount total would pay our other representatives and Senators for several years. It is, probably, as much as ever Vermont contributed towards the whole expence of our national administration. If we had the money Mr. Lyon has cost us, it would now buy the whole of the proportion of the land tax from this State, due to the United States. What is the grand benefit or honor we are to derive from the achievements of the hero of the wooden sword for all this expence? The farmer must pay for his quarrels and the expences of his petulant temper; and if he could affect a revolution of government, they must fight his battles, and bear the consequences of his indiscretions, quarrels and expenditures.

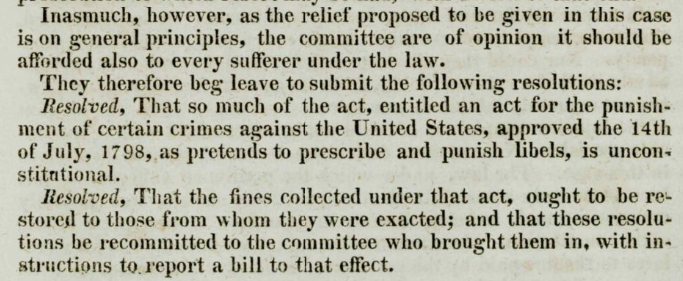

Lyon remained active in politics throughout his life, in Vermont, later in Kentucky, and toward the end of his life in Arkansas Territory. Several years before he died he was vindicated in his opposition to the Sedition Act, when the Senate agreed that law was unconstitutional and that Lyon’s $1,000 fine should be remitted to him:

Resolved, That so much of the act, entitled an act for the punishment of certain crimes against the United States, approved the 14th of July, 1798, as pretends to prescribe and punish libels, is unconstitutional.

Resolved, That the fines collected under that act, ought to be restored to those from whom they were exacted; and that these resolutions be recommitted to the committee who brought them in, with instructions to report a bill to that effect.

The obituary below, from the Arkansas Weekly Gazette, does not exactly “lionize” Lyon, but it does portray him as a man devoted to the public good who lived a worthy life. If he pushed the boundaries of public discourse, he was no less sparing of himself than he was of his opponents. He fought in our wars, created fortunes and lost them, and embodied the American dream wherein a penniless immigrant conveyed into servitude could rise to the highest level of civic engagement.

In private as well as public life, the character of Colonel Lyon stood fair; his manners were calculated to make friends; he was frank, generous and sincere, and never evinced any thing like a vindictive disposition even toward his enemies.

For more information about the Archive of Americana, please contact Readex Marketing.