“All those individuals who, until this day, looked upon themselves as slaves, are free”: The Lost History of the Mexican Underground Railroad

When we are first taught about the Underground Railroad, we learn about following the drinking gourd and how “conductors,” such as Harriet Tubman, helped free enslaved people in the south, ushering them through the north and into Canada. Not nearly as often do we learn how freedom also lay just beyond the U.S. southern border, in Mexico. Nor do we fully understand the impact that the abolishment of slavery in Mexico had on kindling the Texas rebellion and its eventual secession.

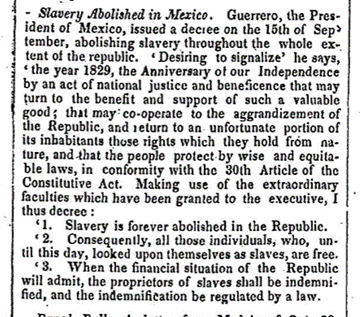

On September 16th, 1829, more than 30 years before Abraham Lincoln issued his Emancipation Proclamation, Mexico abolished slavery. The decree came from President Vicente Guerrero, the first Black President in North America, stating:

‘1. Slavery is forever abolished in the Republic.

‘2. Consequently, all those individuals, who, until this day, looked upon themselves as slaves, are free.

The Guerrero Decree also stipulated that former slaveowners would, in turn, be compensated for the loss of their enslaved people.

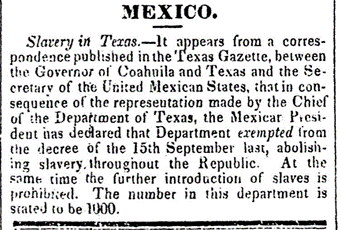

It appears from a correspondence published in the Texas Gazette, between the Governor of Coahuila and Texas and the Secretary of the United Mexican States, that in consequence of the representation made by the Chief of the Department of Texas, the Mexican President has declared that Department exempted from the decree of the 15th September last, abolishing slavery, throughout the Republic. At the same time the further introduction of slaves is prohibited. The number in this department is stated to be 1000.

The ban on the import of slaves and the enforcement of that ban by the Mexican military became one of the catalysts that fueled anger against the Mexican government and led to the annexation of Texas.

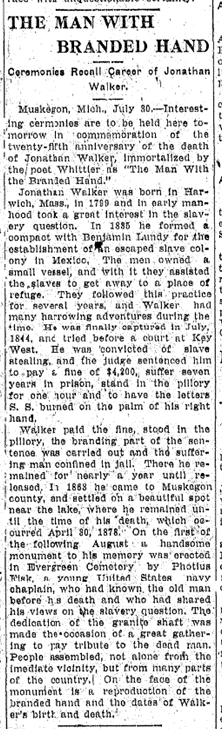

Abolitionists in the United States applauded Mexico’s anti-slavery law and as early as the 1830s, the work to help fugitive enslaved people settle in Mexico had begun. One particular leader of the movement was Quaker Abolitionist Benjamin Lundy. Lundy hoped to work with the Mexican government to set up a free colony for former enslaved persons in Mexican-Texas. He was assisted in his efforts by Captain Jonathan Walker, a ship captain turned “slave stealer.”

Ultimately, their attempts were thwarted by the Texas War of Independence that began in 1835. After the war ended in 1836, Texas was annexed into the United States and instantly, to the fear of many northern abolitionists, became a slave state. Captain Walker moved to Florida and returned to seafaring but never gave up on freeing enslaved people, his motto being “Ever Save, Never Surrender the Slave.” He was eventually caught attempting to smuggle fugitive slaves out of Florida and convicted of stealing slaves.

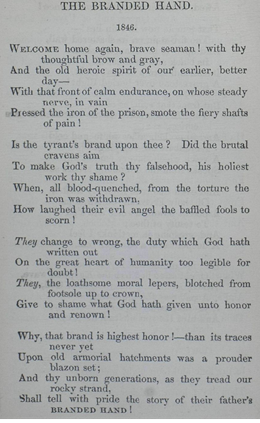

As punishment, Walker was branded with an “S.S” on his hand for ‘Slave Stealer’, sentenced to prison time, and fined. After his release, he continued to speak out against slavery. His acts were also immortalized in a poem entitled “The Branded Hand” by John Greenleaf Whittier.

Tejanos, Mexican descendants of the original Hispanic settlers living in Texas, likewise played a big part in housing and ferrying former enslaved people to freedom, as many opposed the institution of slavery. For many enslaved peoples in Texas and other southern states, the Mexican border was closer than the long, dangerous trip to Canada, thus their only hope for freedom.

The valley beyond the Nueces is fast filling up with a population opposed to slavery, and the day is not far distant when they will become numerically strong enough to carry a longitudinal division of the State, making the western division a Free Soil State.

While many “conductors” led enslaved people to freedom through the northern route, most traveled the southern journey to the Rio Grande alone. Reports of escaped slaves crossing the Rio Grande by any means necessary were often written about in newspapers.

We hear that several negroes have made their way across the Rio Grande into the country of “God and liberty.” Three darkeys lately stole a bale of cotton at Freeport, at night, cast it into the river, and floated across the Rio Grande on it.

After the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850, enslaved people caught in free states were required by law to be returned to their owners in the southern United States. This, however, did not apply to countries such as Mexico and British-owned Canada. This inability to reclaim enslaved people who had escaped to Mexico angered many Texas slaveowners. Over the next decade, many attempts were made to persuade Mexico to sign a treaty to turn over escaped enslaved people, but the Mexican government never yielded.

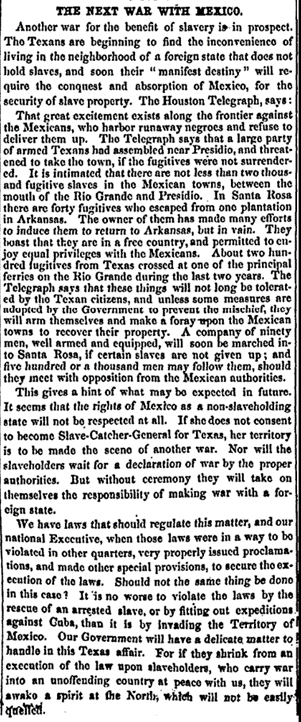

The manner in which the United States handled enslaved people who had escaped across borders was starkly different in its approach to Mexico than to Britain. Many viewed Anglo Britain as strong and would not attempt to threaten the peace with Canada, on the other hand, Mexico was viewed as weak. This juxtaposition was highlighted in an article from The Plain Dealer which states,

We are inclined to think that it will be difficult to make Mexico understand the propriety of compelling her to surrender fugitive slaves, when no such demand is made of Great Britain into whose Canadian Provinces many are yearly escaping. The fact that Mexico is weak and England strong may make all the difference.

Many feared that slaveowners in Texas would start an unsanctioned war against Mexico over the return of their enslaved people. Several Texas slaveowners gathered at the Mexican border and attempted to take back their slaves by force. The Boston Recorder reported on the tensions at the border stating:

The telegraph says that a large party of armed Texans had assembled near Presidio and threatened to take the town, if the fugitives were not surrendered. It is intimated that there are not less than two thousand fugitive slaves in the Mexican towns, between the mouth of the Rio Grande and Presidio.

Despite the threat of attack, Mexico held strong in its beliefs, and a decade later, the United States was fighting the battle over slavery within its own borders. More than three decades after Mexico's decree, President Lincoln issued the preliminary Emancipation Proclamation on September 22, 1862. While the American Civil War would still rage for almost three more years, the United States finally caught up with its neighbors in abolishing slavery.

Learn more about the Mexican underground railroad from Mexican abolishment through reclamation in both the Black Life in America and Hispanic Life in America collections, and our vast collections of historical newspapers and imprints.