Casting Light on the Bomb-Throwers: Revisiting Chicago’s 1886 Haymarket Riot and Its Social Fallout

There’s an ironic twist in the contents of Chicago’s Sunday Inter Ocean newspaper for October 10, 1886, that wouldn’t have been apparent to its readers of that day. Much of the issue was devoted to transcribing the 5-1/2 hour courtroom speech of Albert Parsons, defending himself and seven of his anarchist compatriots against the death penalty for their alleged complicity in the Haymarket Riot of May 4, 1886.

The last act in the great anarchist drama was played yesterday, at least so far as Cook County is concerned. Only the curtain of the gallows needs to be rang down and the drama is ended. So, as the courtroom filled when the doors were opened at 9:45, the specter of death seemed to have entered before them. The vision of eight dangling forms seemed to fill the air with its unwholesome presence.

At least eight people died including seven policemen, with many more injured by the explosion of a bomb and the ensuing gunfire at the end of a labor rally. During the trial, culpability was laid at the feet of radical immigrant labor activists such as Parsons, four of whom were eventually executed despite evidence showing that they could not have thrown the bomb. And on page three of that same paper the following news item appears:

New York. Oct. 9--The arrangement for the ceremonies attending the unveiling of the Bartholdi statue of “Liberty Enlightening the World” are now nearly complete. The representatives of the French Government will sail in a few days.

So while a group composed largely of German immigrants had just been convicted in Chicago of using dynamite to deadly effect in pursuit of the American dream, another group of immigrant laborers in New York was preparing the Statue of Liberty for her debut as the 305-foot-tall embodiment of that dream.

Emma Lazarus’ sonnet was not placed on the Statue of Liberty’s pedestal until 1903, but the symbolism of the “New Colossus” soon became synonymous with her words as a beacon of hope for just such persons as those workers in Chicago and New York:

...Give me your tired, your poor,

Your huddled masses yearning to breathe free,

The wretched refuse of your teeming shore.

Send these, the homeless, tempest-tost to me,

I lift my lamp beside the golden door!”

The Haymarket labor rally was intended by its organizers as a peaceful though vigorous protest against the fatal shooting by police of six men during a strike against the McCormick Reaper Works on May 3, 1886. The specific thrust of that strike was in support of the eight-hour workday as opposed to the then-prevalent business practice of requiring ten hours or more of work each day.

There was legal precedent for the eight-hour movement, as on June 25, 1868, the federal government passed “An Act Constituting Eight Hours a Day’s Work for all Laborers, Workmen and Mechanics Employed by or on Behalf of the Government of the United States.” This law was affirmed several times during the nineteenth century, but was widely disregarded in practice.

The sticking point lay in the demand for ten hours’ wages for eight hours of work. Calls for the law’s application in private industry gained momentum as the labor movement grew following the Civil War. In December 1884 the Federation of Organized Trades and Labor Unions set the date of May 1, 1886, as a deadline following which the eight-hour day was to be implemented across various industries, or strikes would result. A parade in Chicago inaugurated May 1st as a day celebrating the humanity and aspirations of the working class.

Thus far there has been no violence or bloodshed in Chicago as a result of the great eight hour movement which was inaugurated today. Except a slight chill in the atmosphere the weather has been all that it should be on the 1st of May--bright, sunshiny and exhilarating.

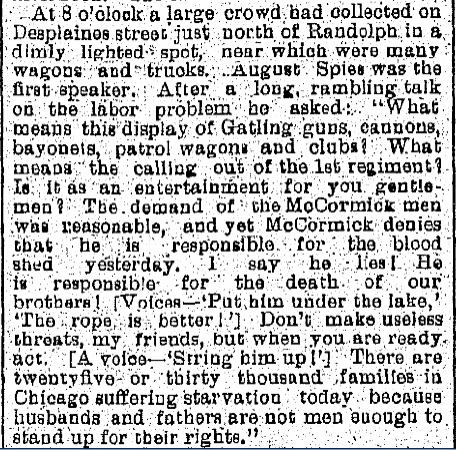

A rally to protest the McCormick shootings was called for on May 4 in Chicago’s Haymarket Square. It began peacefully enough, although the rhetoric of the speakers was highly charged. The crowd gave voice to the tension between the struggling workers and the factory owners whose privilege was reinforced by the militarized police:

At 8 o’clock a large crowd had collected on Desplaines street just north of Randolph in a dimly lighted spot, near which were many wagons and trucks. August Spies was the first speaker. After a long, rambling talk on the labor problem he asked, “What means this display of Gatling guns, cannons, bayonets, patrol wagons and clubs? What means the calling out of the 1st regiment? Is it as an entertainment for you gentlemen? The demand of the McCormick men was reasonable, and yet McCormick denies that he is responsible for the bloodshed yesterday. I say he lies! He is responsible for the death of our brothers! [Voices—‘Put him under the lake,’ ‘The rope is better!’] Don’t make useless threats, my friends, but when you are ready, act. [A voice—‘String him up!] There are twentyfive or thirty thousand families in Chicago suffering starvation today because husbands and fathers are not men enough to stand up for their rights.”

At about 10 PM, rain was threatening and the crowd had begun to thin out. Albert Parsons had already given a rather didactic speech on labor statistics, and had departed to a nearby tavern. Chicago Mayor Carter Harrison, Sr., who was attending the rally simply to hear the views, had also left for home. Anarchist Samuel Fielden mounted the speaker’s wagon and spoke for perhaps twenty minutes when a police detachment of about 150 men began advancing on the crowd, demanding that it disperse.

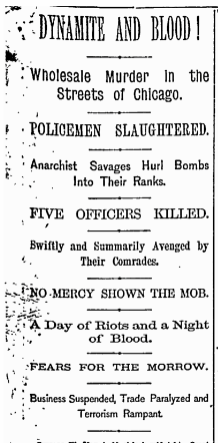

As the police cordon reached the speakers’ wagon, sparks flared off to one side of the street. Those sparks accompanied an object that traced an arc through the air that ended at the patrolmen’s feet. The instant the object hit the pavement it exploded, the concussion and shrapnel ripping through the ranks of police with the fury of an enraged beast. Then the police reformed their lines, and the shooting began.

Witnesses estimate that the police reloaded at least once, and likely shot their fellow officers as well as members of the crowd in the darkness and confusion. When the shooting stopped the street was deserted except for the fallen. Those would include seven policemen and at least one civilian killed, with many more wounded on both sides.

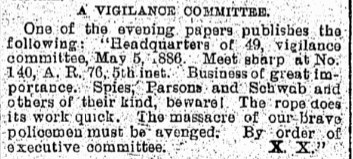

The mood on the streets turned ugly as vigilante groups asserted themselves:

A VIGILANCE COMMITTEE.

One of the evening papers publishes the following: “Headquarters of 49, vigilance committee, May 5, 1886. Meet sharp at No. 140, A.R. 76, 5th inst. Business of great importance. Spies, Parsons and Schwab and others of their kind, beware! The rope does its work quick. The massacre of our brave policemen must be avenged: By order of executive committee, X.X.”

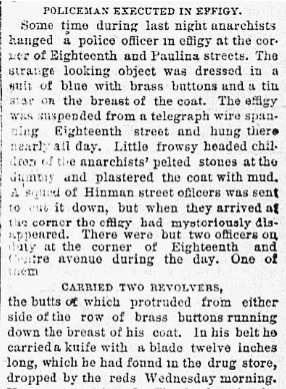

Threats of further violence were not limited to the authorities:

POLICEMAN EXECUTED IN EFFIGY.

Some time during the last night anarchists hanged a police officer in effigy at the corner of Eighteenth and Paulina streets. The strange looking object was dressed in a suit of blue with brass buttons and a tin star on the breast of the coat. The effigy was suspended from a telegraph wire spanning Eighteenth street and hung there nearly all day. Little frowsy headed children of the anarchists’ pelted stones at the dummy and plastered the coat with mud. A squad of Hinman street officers was sent to cut it down, but when they arrived at the corner the effigy had mysteriously disappeared.

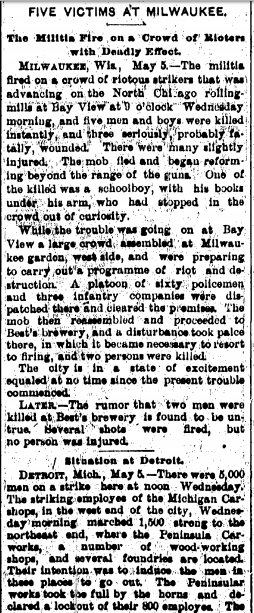

Chicago was not alone as the scene of labor unrest; Milwaukee and Detroit also hosted contemporaneous incidents of strikes and shootings.

MILWAUKEE, Wis., May 5—The militia fired on a crowd of riotous strikers that was advancing on the North Chicago rolling mills at Bay View at 9 o’clock Wednesday morning, and five men and boys were killed instantly, and three seriously, probably fatally, wounded. There were many slightly injured. The mob fled and began reforming beyond the range of the guns. One of the killed was a schoolboy, with his books under his arm, who had stopped in the crowd out of curiosity.

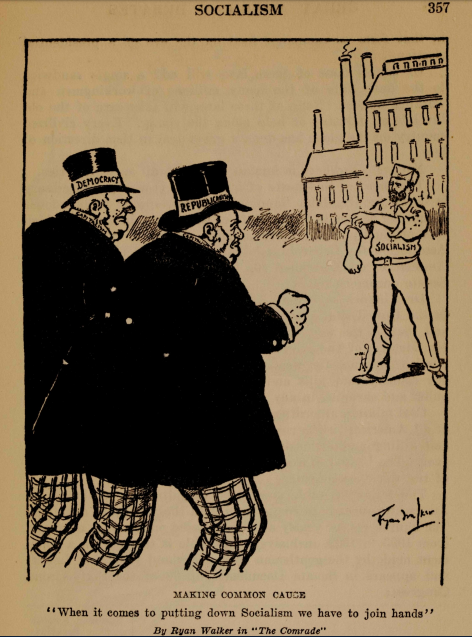

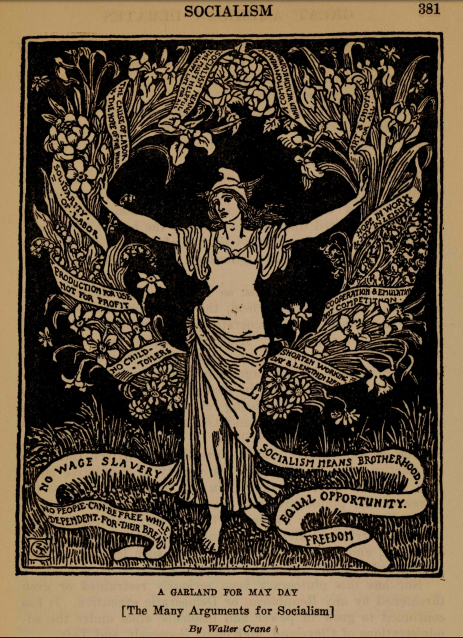

This may be a good point at which to discuss the differences between anarchism and socialism as understood at the time. Remember that this was the Gilded Age, a time of widespread urban poverty and social unrest juxtaposed with great concentrations of wealth, more than a decade before President Theodore Roosevelt began reining in the powerful financiers who dominated economic and political life in America.

Industrialization was proceeding apace. Waves of immigrants swept ashore seeking the promise of America, bringing with them European political ideas such as socialism which blurred the lines of ethnic allegiance shared by many of those recently arrived here.

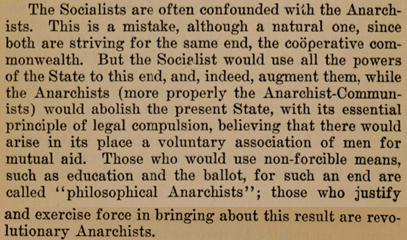

The Haymarket activists styled themselves as anarchists, introducing yet another gradation of social identity. The following excerpt from a work found in The American Slavery Collection distinguishes socialism from anarchism generally thus:

The Socialists are often confounded with the Anarchists. This is a mistake, although a natural one, since both are striving for the same end, the cooperative commonwealth. But the Socialist would use all the powers of the State to this end, and, indeed, augment them, while the Anarchists (more properly the Anarchist-Communists) would abolish the present State, with its essential principle of legal compulsion, believing that there would arise in its place a voluntary association of men for mutual aid.

Communists and anarchists shared the principle that the state should wither away, spurred on by revolutionary means if necessary. On the path to that end was socialism, wherein the workers would take over the means of production and manage their own affairs. But socialists, communists and anarchists alike were united in their loathing for the capitalists and the power structures that supported them.

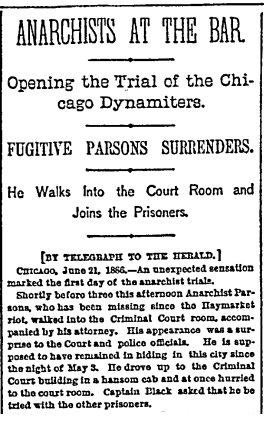

Following the Haymarket riot, August Spies, Samuel Fielden and a number of other activists were soon arrested. Peremptory, warrantless raids were carried out by the police. Albert Parsons initially fled the city, but returned of his own volition to stand trial with the other labor organizers.

An unexpected sensation marked the first day of the anarchist trials.

Shortly before three this afternoon Anarchist Albert Parsons, who has been missing since the Haymarket riot, walked into the Criminal Court room, accompanied by his attorney. His appearance was a surprise to the Court and police officials. He is supposed to have remained in hiding in this city since the night of May 3. He drove up to the Criminal Court building in a hansom cab and at once hurried to the court room. Captain Black asked that he be tried with the other prisoners.

Given the government’s de facto suspension of civil rights following the riot, the result of the trial was a foregone conclusion. Although it was true that the anarchists often preached violence and even prepared for armed confrontations with police, none of the persons convicted were proven to have thrown or known of the fatal bomb. This is not to say that bombs were unknown to the men themselves; Chicago’s Daily Inter Ocean for July 23, 1886, details just how familiar the anarchists were with explosives:

The air of Judge Gary’s court-room was thick yesterday with bombs and fuses and fulminating caps and bars of dynamite and the tongues of counsel oily with glycerine. And bombs too of all sorts. Dainty little bombs, a Jersey cow sort of affair, adapted to being carried in a vest pocket or attached to a watch-chain, or to be used as an ear-pendant by nihilist princesses; and hip-pocket bombs, larger, but not large; and Czar bombs such as the one that annihilated the unfortunate Alexander II, Czar of all the Russias [sic], and adapted for the use of the six-foot anarchist; and bombs as large as a cigar-box, and set off by clock-work, and against which the Tower of London wouldn’t stand the ghost of a chance; and still bigger ones, set off by electricity, and with a capacity for lifting a small planet.

Several persons were proposed as the actual bomb-thrower, but none were proven conclusively to have been guilty of that act. One of the primary suspects, Rudolph Schnaubel, was supposed to have committed suicide during the trial; another account has him leaving the country. Ignatz Swobotka confessed to the crime during an interview in New York prior to leaving the country himself. Neither of these men nor any other were ultimately charged with the offense. However, based upon the ethnic identities of the principal suspects a wave of xenophobia was touched off by the violence, as shown in press coverage of the trial:

Scarcely a witness of the haymarket riot examined by the defense had been in this country as much as ten years. We were alive to the enjoyment of our free and enlightened form of government, but these off-scourings of older countries where liberty was only known in theory, forced to leave their native shores, came here to force their ideas of liberty down our throats with dynamite.

The defense attorney, Captain William P. Black, blamed the police for precipitating the riot and compared his clients to another notable disrupter of social convention, Jesus Christ:

When the followers of the great Socialist of Judea sought to spread the great principles of the teacher, there were those who thought by crucifixion to strangle the great truth. But it would not be strangled. It burst forth in spite of the puny efforts of its foes and enveloped the world. Capt. Black concluded his address to the jury as follows: “These defendants stand in this room true to their convictions. Let us change those convictions, if we can, by argument. Let us persuade them, if we can that they shall not do violence. But I tell you that if the only answer you have to them is the hemp and noose, you are turning back to the barbarism of eighteen hundred years ago. You recant the thought and passion and inspiration of God in this great hour of civilization.

Despite such entreaties the eight men were convicted:

The jury which has been engaged in the trial of the eight anarchists, August Spies, Michael Schwab, Samuel Fielden, Albert R. Parsons, Adolph Fischer, George Engel, Louis Lingg, and Oscar W. Neebe, rendered a verdict of guilty in all the cases, with the penalty of death in each case, except Neebe, who is given fifteen years in the penitentiary.

Albert Parsons, for one, had a lot to say about the verdict. The following are a few excerpts from a speech he gave that lasted from 10 in the morning to 3:30 that afternoon. Consider the “Occupy Wall Street” demonstrations, the campaign against the “one percent” who own a disproportionate share of the country’s resources, and the ongoing political battle over raising the minimum wage, then read Parsons’ words from over one hundred years ago:

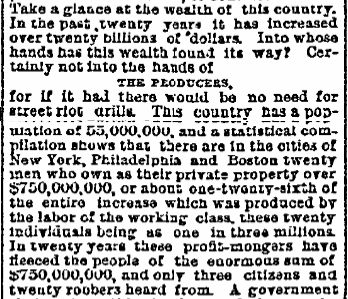

Take a glance at the wealth of this country. In the past twenty years it has increased over twenty billions of dollars. Into whose hands has this wealth found its way? Certainly not into the hands of the producers, for if it had there would be no need of street riot drills. This country has a population of 55,000,000, and a statistical compilation shows that there are in the cities of New York, Philadelphia and Boston twenty men who own as their private property over $750,000,000, or about one-twenty-sixth of the entire increase which was produced by the labor of the working class, these twenty individuals being as one in three millions. In twenty years these profit-mongers have fleeced the people of the enormous sum of $750,000,000, and only three citizens and twenty robbers heard from.

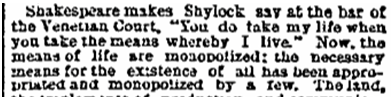

Shakespeare makes Shylock say at the bar of the Venetian Court, “You do take my life when you take the means whereby I live.” Now, the means of life are monopolized; the necessary means for the existence of all has been appropriated and monopolized by a few.

The verdict was appealed to the Illinois Supreme Court where it was denied, and to the U.S. Supreme Court, which refused to review the case. Illinois Governor Richard J. Oglesby would later commute the sentences of Fielden and Schwab, but refused to intercede in the cases of Parsons, Spies, Engel and Fischer who were hanged on November 11, 1887. Lingg committed suicide on the eve of his execution. Fielden, Neebe and Schwab were pardoned in 1893.

Even in its day, the verdict was widely viewed as a miscarriage of justice. Readex’s American Pamphlets collection includes two titles which make that argument at length. Both are by Gen. Matthew Mark Trumbull, himself an immigrant from England who started out as a laborer and later earned his exalted rank fighting for the Union with the Third Iowa Infantry in America’s Civil War.

![Was It a Fair Trial? An Appeal to the Governor of Illinois. [by] Gen. M.M. Trumbull, in Behalf of the Condemned Anarchists. [1886]. From American Pamphlets, 1820-1922: From the New-York Historical Society Bomb Throwers Image 23.png](/sites/default/files/blog/Bomb%20Throwers%20Image%2023.png)

In answer to the title’s question, Was It a Fair Trial?, Trumbull maintains that although Parsons and the other anarchists were provocative even to the building of bombs, they were not guilty of the murders for which they were tried, and that their trial was irregular and unfair in numerous ways.

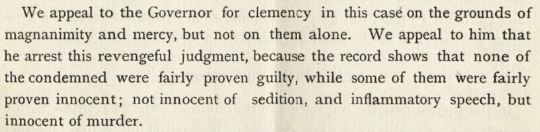

We appeal to the Governor for clemency in this case on the grounds of magnanimity and mercy, but not on them alone. We appeal to him that he arrest this revengeful judgment, because the record shows that none of the condemned were fairly proven guilty, while some of them were fairly proven innocent; not innocent of sedition, and inflammatory speech, but innocent of murder.

The pamphlet quoted above is the original 20-page version of a later expanded critique that was published in several editions between 1888-1890 after Albert Parsons, George Engel, Adolph Fischer and August Spies were executed. Trumbull explains in the preface that The Trial of the Judgment was cast as an “indictment against the judgment in the anarchist case.”

Trumbull makes a number of compelling points, among them that the men were tried as a group for a conspiracy that was never proven to exist, with circumstantial evidence against one serving to convict them all. Illinois Supreme Court Justice John H. Mulkey agreed with Trumbull, although not to the extent of authoring a dissenting opinion in the case:

In view of the number of defendants on trial, the great length of time consumed in the trial, the vast amount of testimony offered and passed upon by the court, and the almost numberless rulings the court was required to make, the wonderment to me is the errors were not more numerous and of a more serious character than they are.

In Trumbull’s words,

This doctrine of cumulative responsibility, joint and several, is worthy of a reign of terror. Under it, not only freedom of public speech will be destroyed, but freedom of private speech also. Social confidence will disappear, and no man will dare to utter his political opinions in conversation with his neighbor.

Trumbull teases out the inconsistencies in the cases against all of the men. Here’s his summary regarding Albert Parsons:

The Supreme Court makes Parsons guilty on the ground that he was present at the Haymarket meeting and spoke. The court acknowledged that he was in Cincinnati on Monday, and knew nothing at all about the pretended conspiracy claimed to have been formed that night. It was conceded that the speech of Parsons was moderate in tone, that he had his wife and children with him, that he left before the arrival of the police, did no pistol shooting, gave no signal, and was not present when the bomb was thrown. But he was present at the meeting in company and association with Fielden, and thus adopted the “conspiracy” of Monday night, although he never knew a word about it.

Trumbull’s conclusion is the same as that given by Illinois Governor John P. Altgeld for pardoning Fielden, Neebe and Schwab in 1893:

Seditious writing and inflammatory speech are not murder, but capital punishment inflicted upon men for either offense, is murder.

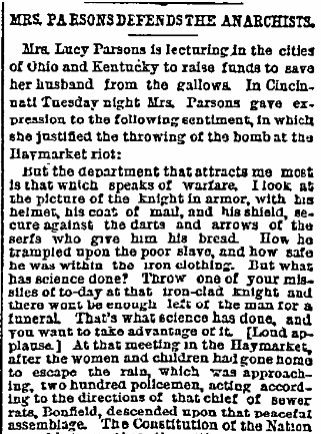

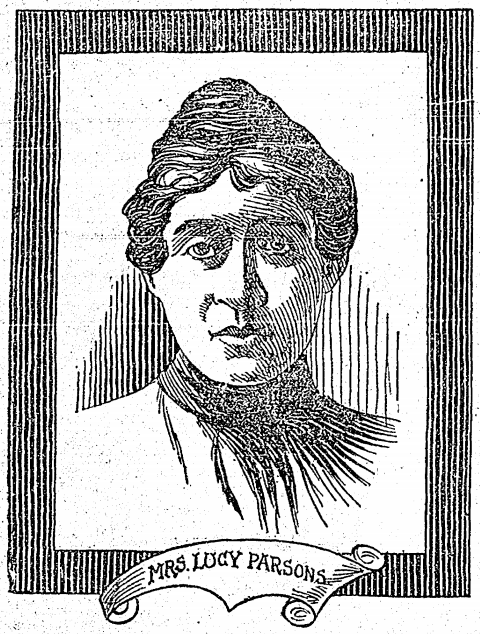

Albert Parsons’ wife, Lucy, in many respects a more formidable and committed revolutionary than her husband, was unrelenting in her criticism of the verdict, and unsparing in her remedy for such injustice. Here she is in Cincinnati:

I look at the picture of the knight in armor, with his helmet, his coat of mail, and his shield, secure against the darts and arrows of the serfs who give him his bread. How he trampled upon the poor slave, and how safe he was within his iron clothing. But what has science done? Throw one of your missiles of to-day at that iron-clad knight and there won’t be enough left of the man for a funeral. That’s what science has done, and you want to take advantage of it. [loud applause]

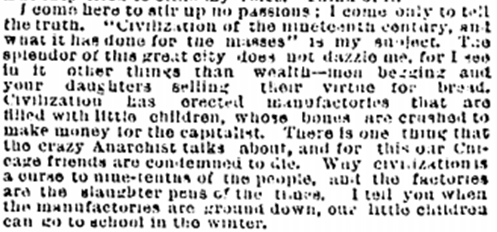

In New York City she presented the social side of her argument:

The splendor of this great city does not dazzle me, for I see in it other things than wealth--men begging and your daughters selling their virtue for bread. Civilization has erected manufactories that are filled with little children, whose bones are crushed to make money for the capitalist. There is one thing that the crazy Anarchist talks about, and for this our Chicago friends are condemned to die. Why civilization is a curse to nine-tenths of the people, and the factories are the slaughter pens of the times.

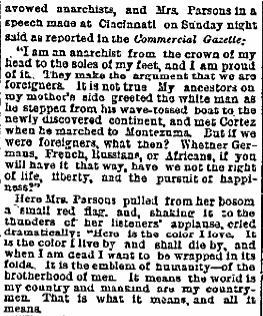

At another speech in Cincinnati she addressed the discrimination against immigrants that was so telling in the social mores of the time:

I am an anarchist from the crown of my head to the soles of my feet, and I am proud of it. They make the argument that we are foreigners. It is not true. My ancestors on my mother’s side greeted the white man as he stepped from his wave-tossed boat to the newly discovered continent, and met Cortez when he marched to Montezuma. But if we were foreigners, what then? Whether Germans, French, Russians, or Africans, if you will have it that way, have we not the right of life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness?

In point of fact, according to research done by Dr. Jacqueline Jones of the University of Texas at Austin, Lucy Parsons was born a slave in Virginia, likely from the union of her enslaved mother with a Confederate surgeon named Tolliver who moved to Texas with his household following the Civil War.

Parsons reinvented herself for a number of reasons, purposefully obscuring her origins. She was largely self-educated, yet was a forceful and eloquent advocate for those causes in which she believed. She would go on to write and edit numerous articles and publications, among them The Liberator.

Here she is in her editorial voice in that venue, in words that are as compelling today as they were in 1905 when she wrote them.

In this age of quick transmission of thought, when all our energies are strained to learn more and more about the sayings and doings of our fellow beings, and especially those who are engaged in the same line of work with ourselves, it becomes absolutely necessary for us to have a medium of exchange if we are to keep in touch with each other, and if we are to do any effective work.

I believe we have all felt this need most intensely since the suspension of FREE SOCIETY.

THE LIBERATOR comes to fill this want.

When Lucy Parsons died in Chicago during a house fire on March 8, 1942, at the age of 83, according to her Chicago Tribune obituary she was still so notorious that the FBI confiscated her entire personal library and has yet to account for it. It would be a tribute to her advocacy for civil rights and a garland to her memory if her library were released or its disposition otherwise documented.

For more information about Readex resources, including Early American Newspapers, American Pamphlets, Hispanic American Newspapers and The American Slavery Collection, please contact Readex Marketing.