A Name to Conjure With: Mardi Gras Indians Keep the Faith through the Spirit of Sauk War Leader Black Hawk

The spirit of Black Hawk is alive and well and living in New Orleans. How does the influence of this Sauk war leader inform Creole identity over 250 years after his birth? The answer involves a rich gumbo of Native American and African American culture with dashes of American Spiritualism and the iconography of Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Show.

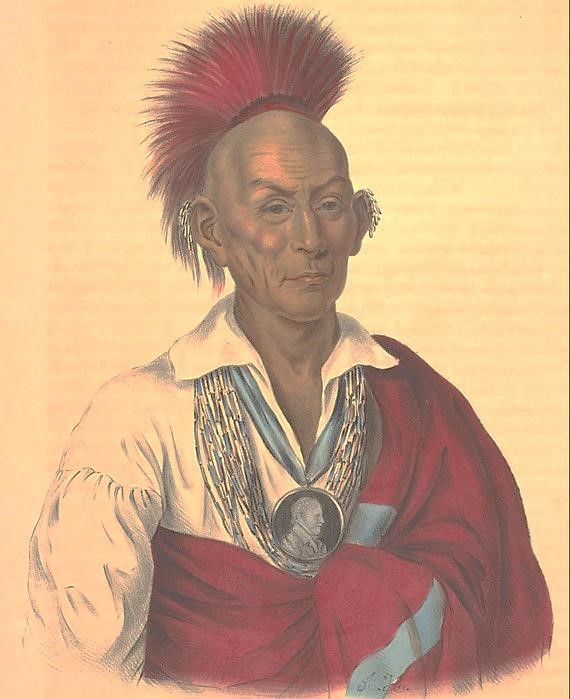

Black Hawk (Muk-a-tá-mish-o-ká-kaik) was born to a prominent Sauk family in 1767 in Saukenuk, present-day Rock Island, Illinois. He distinguished himself in battle during numerous campaigns against other Indian tribes and thus became influential although he was not a hereditary chief. Life was good for Black Hawk’s band in the years leading up to the 1820s. But it did not last. Edwin D. Coe recounted Black Hawk’s trajectory in an 1896 pamphlet from Readex’s American Pamphlets:

Life passed pleasantly with Black Hawk and his tribe at Saukenuk for many years. The location combined all the advantages possible for their mode of existence. When Black Hawk was taken to Washington after his capture in 1832, he made an eloquent and most pathetic speech at one of the many interviews which he held with the high officials of the government. He said: “Our home was very beautiful. My house always had plenty. I never had to turn friend or stranger away for lack of food. The Island was our garden. There the young people gathered plums, apples, grapes, berries and nuts. The rapids furnished us fish. On the bottom lands our women raised corn, beans and squashes. The young men hunted game on the prairie and in the woods. It was good for us. When I see the great fields and big villages of the white people, I wonder why they wish to take our little territory from us.”

In 1831 Black Hawk’s band was driven from their homeland by squatters and through enforcement of the disputed 1804 Treaty of St. Louis. They relocated west of the Mississippi River and suffered greatly from inadequate food and shelter. Black Hawk then resolved to reclaim their former territory and prosperity, and began raiding settlements across the river.

He sought allies among the Sauk and other tribes but met with disappointment; the Americans were simply too numerous and well organized. During the War of 1812 the Sauk had fought in confederacy with Great Britain against the United States; in 1831 he looked again for British support. When this was not forthcoming he nonetheless escalated his raids in what became known as the 1832 Black Hawk War. A passage from Readex’s U.S. Congressional Serial, 1817-1994, summarizes that conflict:

The same year (1832) witnessed the culmination of the hostile aggressions of the Sac and Fox Indians upon the borders of Illinois and Michigan, that had been going on since the earliest settlements. While there was never any serious doubt as to the ability of these States to take care of themselves, these constant and unprovoked aggressions seemed to render a severe lesson necessary in the trust that its impression would be permanent and salutary. To this end a campaign having been determined upon, the executives of the States of Missouri, Illinois, Indiana, and of the Territory of Michigan were called upon to furnish a small quota of militia, and these, to the number of 3,000, in combination with some 1,500 regular troops, were concentrated under the command of Brigadier-General Atkinson, and in June-July moved in several columns upon the Indians. The campaign terminated in the unqualified submission of the hostile tribes, and the adoption of measures for the permanent security of the frontier.

Initially Black Hawk enjoyed success in routing the poorly trained militia sent to apprehend him, which bolstered his hopes for driving the settlers back from the frontier. In fairness to Black Hawk he had not agreed to cede his lands to the United States, and claimed that those Indians who may have done so were not authorized to represent his tribe. In defense of American efforts to end Sauk raids, however, Black Hawk had agreed to remain west of the Mississippi when he relocated there in 1831. He had broken that pledge, and set out to conduct more extensive operations against the settlements.

In the end, the result was much as other tribal leaders had predicted: the regular U.S. troops hunted down the Sauk band, and only a few of that number survived. Black Hawk himself sought refuge with a neighboring tribe but later turned himself in. The last panel of a comic strip from 1931 has him taking leave of his people in the following words:

Farewell, my nation! Black Hawk tried to save you and avenge your wrongs. He has been taken prisoner and his plans are stopped. He can do no more; his sun is setting and will rise no more. Farewell to Black Hawk!

A newspaper article in Readex’s Territorial Papers of the United States, 1764-1953, described the defeat of Black Hawk literally as a watershed moment in the history of American colonization. Since that time the Black Hawk War has acquired the character of a just and noble struggle against overwhelming odds.

Up to 1832, the plains of Iowa were the hunting ground of the Indians. In 1832, soon after the termination of the Black Hawk war settlers began to cross the Mississippi and locate on the Black Hawk purchase; and from that day the flood gates of emigration were opened, and since a rapid tide of emigration has been constantly setting into the new territory.

Among the indignities heaped upon them, it’s often overlooked that Native American Indians were kept as slaves by conquering tribes and colonists alike. An interesting account of both circumstances during the Tuscarora War appears in a 1903 pamphlet by Alfred M. Heston relating to the history of slavery in New Jersey.

An instance of the capturing of Indians for slaves is found in the account of the Tuscarora war, in North Carolina. When the attack began, in 1711, Governor Hyde, of North Carolina, sent to the Governor of South Carolina for aid. He directed his agents there not to fail to represent “that great advantage may be made of slaves, there being many of them, women and children—may we not believe three or four thousand?” The Indian allies, coming from South Carolina to aid Hyde, took back a great number of slaves from the conquered people in North Carolina. The Indians, said Colonel Pollock, as soon as they had taken the fort and secured their slaves, marched away straight to their homes. Tom Blount, chief of a tribe of friendly Indians in that section, also secured his captives for slaves. He proposed to attack a certain small tribe, in which he thought there might not be enough people to give each of his own warriors an Indian slave, and he accordingly asked the North Carolina Council to promise some reward to those who might not happen to have slaves allotted to them. Most of the Indian slaves taken in this Tuscarora war were carried to other colonies, a good many going to Massachusetts and Connecticut. They were sold for about ten pounds each. More than 700 of them were captured and sold before the war was ended.

Facing similar persecution at the hands of European colonists, it’s not surprising that in many cases runaway African slaves sought refuge, intermarried or allied themselves with Native American tribes. For example, an account of the 1729 Natchez Revolt from Martin’s History of Louisiana (1882) described the identity of interests that existed among the Natchez Indians and the African slaves in the area. “Perrier” refers to the French Territorial Governor Étienne Périer, who organized the military response to the revolt.

Perrier had collected about three hundred soldiers; having sent for those at Fort St. Louis and Fort Conde. Three hundred men of the militia had joined this force, and he was preparing to march at their head when it was discovered that the negroes on the plantations evinced symptoms of an intention of joining the Indians against their masters, in the hope of obtaining their liberty, as some had done at the Natchez.

Today, the coalescence of African American and Native American culture as personified in Mardi Gras Indians has become symbolic of New Orleans’ joie de vivre. But it wasn’t always so. The apparent cultural appropriation of African Americans adopting Native American dress and mannerisms when masquerading as Indians during Mardi Gras apparently began during the nineteenth century as a dramatic protest against government oppression during Reconstruction.

Around 1885, an African American group calling itself “Creole Wild West” dressed as Plains Indians and marched in Mardi Gras processions. The maskers’ motivation was said to derive from their identity with oppressed peoples and the legacy of escaped slaves who sought refuge with Indian tribes. Their costumes followed the model of the Native American participants in touring Wild West shows that were popular at the time.

It’s plausible that this was the case as Buffalo Bill’s spectacle was indeed wintering in New Orleans in February 1885, and similar Western entertainments such as Carver’s Wild West Show commonly visited that city. Early American Newspapers includes a reference to persons masquerading as Plains Indians even earlier, in 1876.

Imagine all the stores closed and a general suspension of business. The tellers in the counting houses and workshops taken to the fireside, the fields, with dog and gun, or to church; and the roysterous parading the streets in dominoes and costumes in New Orleans on Mardi Gras. Indians from the plains, knights and armored soldiery from the feudal period, turbaned wanderers from the Orient, comprehend in a general way the characters one meets in the streets. The urchins, particularly conspicuous, are to be seen in an irrepressible state of delight, rigged out in the most absurd and incongruous toggery marching everywhere in bands to the rattle of diminutive drums.

The preeminence in the black community of at least one Native American Indian is not in dispute. Namely, that of Black Hawk himself as a forceful presence in the American Spiritualist Church, a Christian denomination that dates to the mid-nineteenth century.

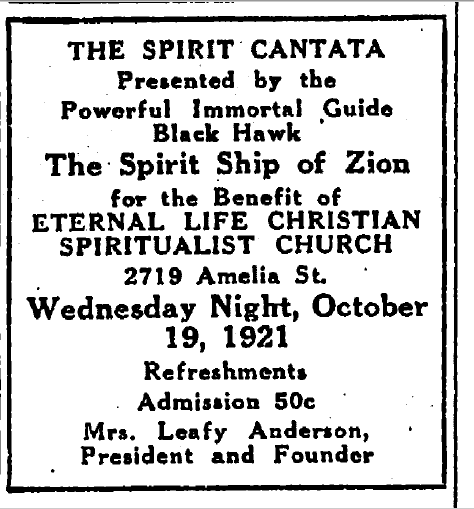

The founder of this branch of American Spiritualism was Rev. Leafy Anderson, known to the faithful as “Mother.” Born in 1887, Anderson claimed both black and Mohawk ancestry. She established her first church in Chicago around 1913, and founded the Eternal Life Christian Church in New Orleans in 1920. When she died in 1927 she had thirteen congregations in at least nine cities.

One of the tenets of her teaching was that “spirit guides” could be personally called upon or mediated in times of need similar to how Roman Catholics pray to saints for intercession in worldly affairs. Spiritualism in New Orleans is sometimes linked to voodoo but its adherents reject that association. Anderson’s services were often dramatic such as in “The Spirit Cantata,” advertised above. One version of that work characterized it as, “A White Man’s Sin and a Squaw’s Revenge.” In Leafy’s pantheon Black Hawk especially was called upon to rescue oppressed people from injustice.

To summarize then we have Black Hawk, a famous Sauk war leader who in 1832 fought a doomed campaign to reclaim his homeland. His spiritual identity was adopted by the African American Spiritualist Church in New Orleans around 1920. We have the Afro-Indian residents of New Orleans who around 1885 began appearing in the habit of Plains Indians during Mardi Gras processions, perhaps as an expression of solidarity with oppressed/rebellious tribes. We have the various Wild West shows that were touring the country in the late nineteenth century which we know stopped in New Orleans. And we also know that escaped African slaves at times sought refuge with and fought alongside Native American tribes.

As an example of the variety of Native American tribes in and around New Orleans we can refer to John R. Swanton’s 1909 map from Readex’s U.S. Congressional Serial Set, 1817-1994. At the northern border of the map the Quapaw Indians (highlighted in red) lived just on the margin of what we today consider the southern boundary of the Plains Indians. As the map indicates, the Quapaws partook of Siouan (Dakotan) traditions.

Like New Orleans itself, the origin of the Mardi Gras Indians involves a collision of cultures—African, Caribbean, Native American, and European. It takes nothing away from African American heritage to allow that the first maskers were as impressed by the prowess and dignity of the Indians they encountered in the Wild West Shows as they were by the grandeur of their ceremonial dress. It’s entirely possible that some of those revelers had lived with native peoples, and immediately grasped the political impact of appearing in public dressed for battle, as indeed they were in those early days.

Surely during that festive season when men dress as women, women as men, when mortals adopt the raiment of gods and goddesses, and multitudes shed their inhibitions prior to the Christian stringencies of Lent, there is a place for the loving tribute of one group of oppressed people for another.