Out of Africa: Ota Benga’s Journey from the Congo to a Cage at the Bronx Zoo

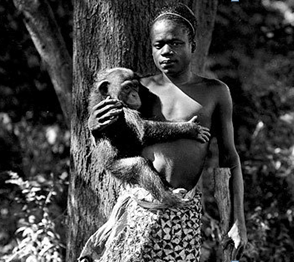

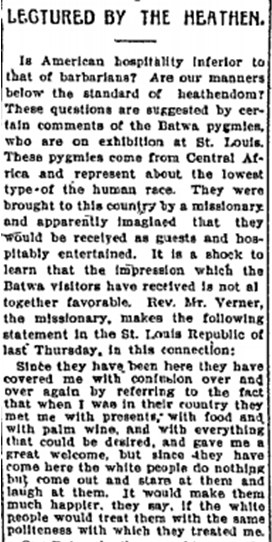

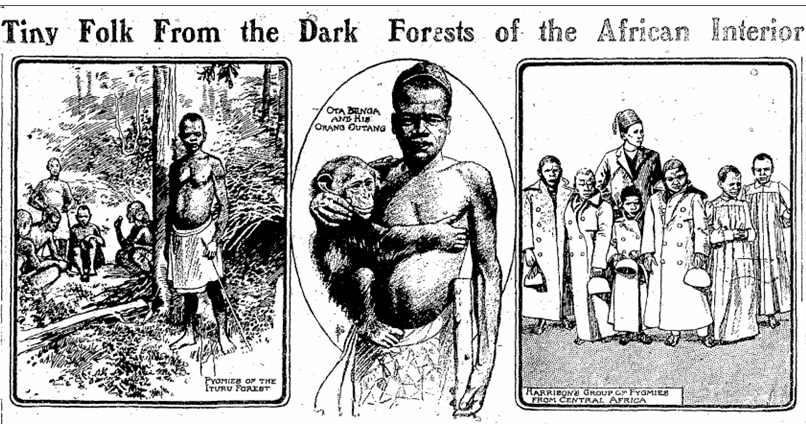

LECTURED BY THE HEATHEN—Is American hospitality inferior to that of barbarians? Are our manners below the standard of heathendom? These questions are suggested by certain comments of the Batwa pygmies, who are on exhibition at St. Louis. These pygmies come from Central Africa and represent about the lowest type of the human race. They were brought to this country by a missionary, and apparently imagined that they would be received as guests and hospitably entertained. It is a shock to learn that the impression which the Batwa visitors have received is not altogether favorable.

It was just a passing notice in the press, a minor commentary on the spectacle that was the 1904 World’s Fair, held in St. Louis and also known as the Louisiana Purchase Exposition. Compared with the general trend of the newspaper coverage of indigenous people displayed at the fair, this article was marked by the charitable tone of the correspondent. Despite the implicit racism of “heathen” being placed “on exhibition” and judged as less highly evolved, the writer here was at least sympathetic to the Africans’ claims.

Just how far short of the ideal of hospitality Americans fell would only be revealed in the coming several years; 1904 would not be the last time a Congolese native would find himself the object of popular scrutiny, nor even the most egregious instance of it.

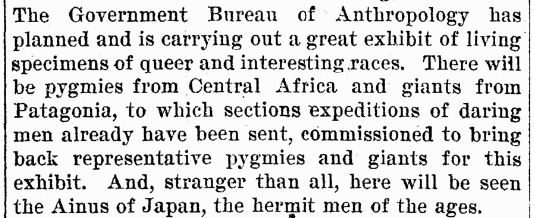

Around 1902 Samuel Phillips Verner, a Presbyterian missionary from South Carolina, was retained by W.J. McGee, Acting Director of the Bureau of American Ethnology of the Smithsonian Institution, to induce African bushmen, particularly the fabled “Pygmies,” to come to America for exhibition at the 1904 World’s Fair. Verner had experience in Africa, ability with native languages, bona fides as a Christian missionary, and aspirations as a man of science. He readily agreed to take McGee’s assignment.

The Government Bureau of Anthropology has planned and is carrying out a great exhibit of living specimens of queer and interesting races. There will be pygmies from Central Africa and giants from Patagonia, to which sections expeditions of daring men already have been sent, commissioned to bring back representative pygmies and giants for this exhibit.

This was the era when Belgium and other countries were struggling to assert colonial dominion over the Central African people. The larger European goal was the development of the rubber and ivory trades among others, in pursuit of which Belgian King Leopold II’s colonial troops, the Force Publique, terrorized and repressed the native people.

![Detail of the Belgian Congo, with the Kasai River running vertically left of center. [Study Mission to Africa, September 1st to December 10th, 1955.] September 1, 1955. From the U.S. Congressional Serial Set Benga 4.png](/sites/default/files/blog/Benga%204.png)

In the spring of 1903 while traveling on the Kasai River, Verner came upon Ota Benga. Benga, a member of the Bachichi tribe, was held captive by the hostile Baschilele people after Benga’s hunting party and family had been slaughtered by the Force Publique. Verner ransomed him with a pound of salt and a bolt of cloth, and utilized the goodwill thus obtained to recruit other natives for travel to America.

Verner arrived in New Orleans in June 1904 with Ota Benga and a small group of men from a related tribe. Their small stature and reputations as cannibals piqued the public interest, and they were heralded as sensations wherever they were exhibited.

Malanga, one of the pygmies confesses that he is a man eater. With pride he refers to a morning when he breakfasted off a missionary in the wilds of the Congo Free State. His taste has changed, and probably he would refuse to eat human flesh if it were now offered him, for he has become partly civilized and has as much relish for ordinary food as any other person.

The Africans even participated in athletic competitions against other indigenous peoples at the fair. This was not entirely flattering to the persons involved as it included such crude activities as mud-throwing. However, a report from The Boston Journal tells us that the Congolese nonetheless asserted their dignity and attained their desire for watermelon rather than money before agreeing to perform, even as they played into American racial stereotypes.

With great painstaking the Pigmies were gathered and an interpreter was obtained who dilated upon the beauty and intrinsic value of the precious metal offered as prizes. But it was of no avail. No gold for the Pigmies. The watermelon plank in their platform was vehemently reaffirmed.

As a result watermelons won the day. Hopeless of any other solution, the managers added watermelons in addition to the cash prizes, and the races were successfully run. It was a great day, and the Pigmies won their share of the fruits of victory.

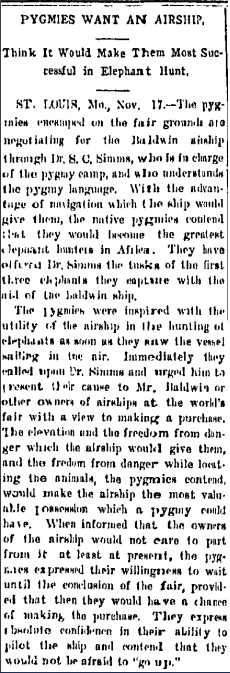

While Benga and his follow Congolese labored as curiosities under the public gaze, they were also keen observers of technological phenomena. For example, they foresaw the potential of hunting big game from the air.

The pygmies encamped on the fairgrounds are negotiating for the Baldwin airship through Dr. S.C. Simms, who is in charge of the pygmy camp, and also understands the pygmy language. With the advantage of navigation which the ship would give them, the native pygmies contend that they would become the greatest elephant hunters in Africa. They have offered Dr. Simms the tusks of the first three elephants they capture with the aid of the Baldwin ship.

The Africans had some reasonable expectation for the use of such things, for Verner had agreed to take the men back to the Congo at the conclusion of the fair. In 1905 he made good on his promise. Following his return to Africa Benga remarried, only to lose his second wife to a bite from a poisonous snake, at which point he decided that living without a tribe or family in the Congo was less desirable than returning to America with Verner. They arrived in New York City in August 1906.

Since Verner was short of funds and intent on spending time with family in South Carolina, he transferred the animals and artifacts he had gathered during his travels—and Ota Benga—to Hermon Carey Bumpus, Director of the American Museum of Natural History in New York, until he returned. Benga was given a room in the museum and could roam freely, but became frustrated at being kept inside. After several weeks, when he threw a chair at philanthropist Florence Guggenheim rather than fetching one for her during a private function, he wore out his welcome and Verner was summoned to make other housing arrangements for him.

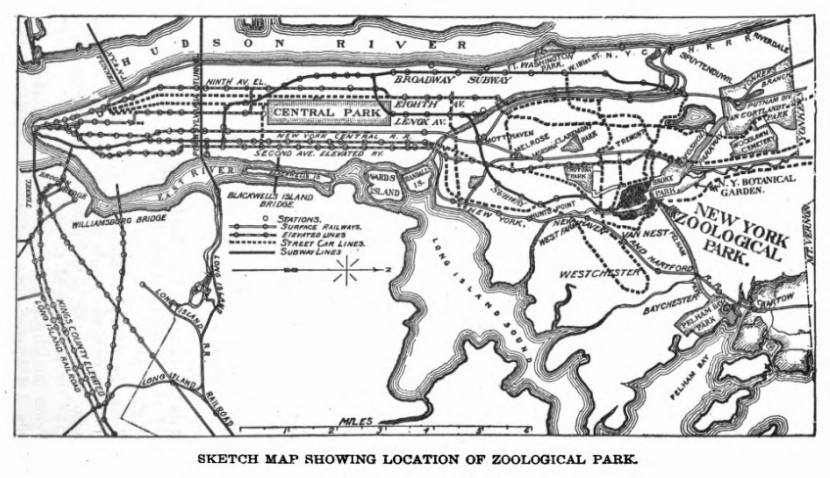

He was then placed with the New York Zoological Society at its Bronx Zoo under the direction of William Temple Hornaday. Benga was given a menial position, a room and the run of the park. When Hornaday noticed the attention that Benga himself attracted from the public, he persuaded him to spend time in a hammock in the primate house, ostensibly to care for the animals there.

Thus for about three weeks from September 8, 1906, Benga became the prime attraction in the Monkey House. While there he befriended an orangutan named “Dohong,” demonstrated his skills at weaving, and shot arrows at a target on a hay bale in an enclosure littered with bones to suggest cannibalism.

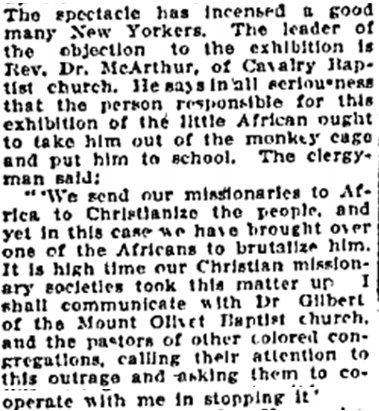

Benga’s exhibition drew immediate criticism from the Colored Baptist Ministers Conference. Robert Stuart MacArthur of Calvary Baptist Church decried it as a disgrace and an insult to Negroes.

The spectacle has incensed a good many New Yorkers. The leader of the objection to the exhibition is Rev. Dr. McArthur, of Calvary Baptist church. He says in all seriousness that the person responsible for this exhibition of the little African ought to take him out of the monkey cage and put him in school. The clergyman said:

“We send our missionaries to Africa to Christianize the people, and yet in this case we have brought over one of the Africans to brutalize him. It is high time our Christian missionary societies took this matter up. I shall communicate with Dr. Gilbert of the Mount Olivet Baptist Church, and the pastors of other colored congregations, calling their attention to this outrage and asking them to cooperate with me in stopping it.”

The ministers were further alarmed that Darwin’s theory of evolution was implicitly validated by portraying Benga on an equal footing with primates. From that low point, things grew steadily worse.

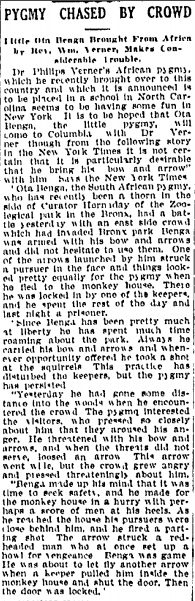

Whenever Benga was out of the Monkey House roaming the grounds, the Congolese man was relentlessly harassed.

Yesterday he had gone some distance into the woods when he encountered the crowd. The pygmy interested the visitors, who pressed so closely about him that they aroused his anger. He threatened with his bow and arrows, and when the threats did not serve, loosed an arrow. This arrow went wide, but the crowd grew angry and pressed threateningly about him.

Benga made up his mind that it was time to seek safety, and he made for the monkey house in a hurry with perhaps a score of men at his heels. As he reached the house his pursuers were close behind him, and he fired a parting shot. The arrow struck a red-headed man who at once set up a howl for vengeance. Benga was game. He was about to let fly another arrow when a keeper pulled him inside the monkey house and shut the door. Then the door was locked.

The keepers at the zoo had some rapport with Benga, but weren’t above having a little “fun” at his expense:

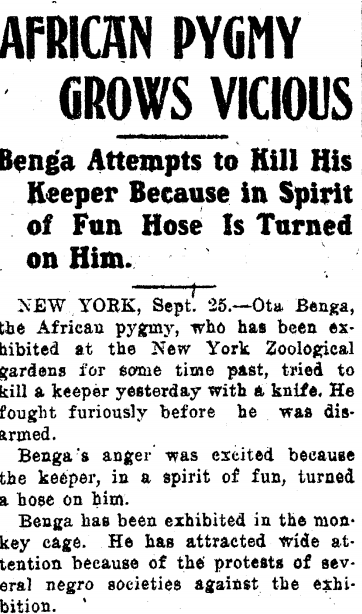

Ota Benga, the African pygmy, who has been exhibited at the New York Zoological gardens for some time past, tried to kill a keeper yesterday with a knife. He fought furiously before he was disarmed.

Benga’s anger was excited because the keeper, in a spirit of fun, turned a hose on him. Benga has been exhibited in the monkey cage. He has attracted wide attention because of the protests of several negro societies against the exhibition.

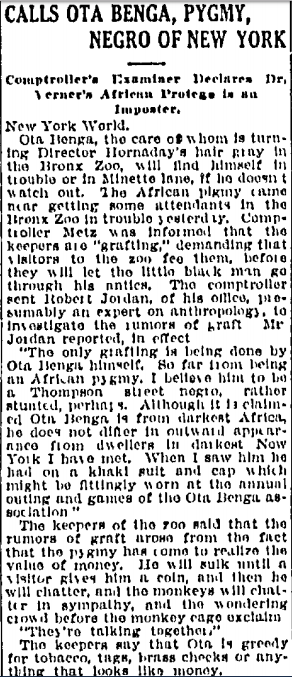

Benga was criticized both for what he was, and for what he was not. A purported “expert on anthropology” quoted in the New York World was sent to evaluate whether “graft” was taking place by requiring visitors to pay fees to induce Benga to pose for them. Far from impugning the behavior of any unscrupulous keepers who might be enriching themselves, the man cast aspersions on Benga himself:

So far from being an African pygmy, I believe him to be a Thompson Street negro, rather stunted, perhaps. Although it is claimed that Ota Benga is from darkest Africa, he does not differ in outward appearance from dwellers in darkest New York I have met.

Despite Benga’s alleged ancestry as a native New Yorker, he was not overly impressed by the city:

Arriving in New York, everybody aboard ship expected the pygmy would exhibit all the signs of ox-eyed wonder. He gazed at the tall buildings, at the electric cars, and the rush and excitement of our streets without any special interest. Asked what he thought of the matter, he exclaimed: “Witchcraft! All is witchcraft. It will come to naught!”

He rode up broadway looking at all the tall buildings without batting an eyelash.

“Nothing wonderful about them—if any one wanted to build them!” he intimated.

After about three weeks Hornaday capitulated to the ministers’ demands and released Benga to the care of Rev. James H. Gordon, Director of the Howard Colored Orphan Asylum in Brooklyn, New York. Verner played down this change of affairs.

Of course talk about ‘exhibiting’ him at the New York zoo is all nonsense, started by the fulminations of the sensation-mongering McArthur, who was aptly described by Dr. Blackburn of this city as ‘a yellow journal in the pulpit.’ But if Ota and I want to give an exhibition, we shall certainly do so when and where we please, with the consent of the law and the approval of the public. He is now visiting some colored people in Brooklyn and enjoying himself immensely.

This latter part was true, for at the Howard Colored Orphan Asylum Ota found a family environment enhanced by an Egyptian laborer with whom he was able to converse.

The Alexandrian during his wanderings has acquired many languages. Ota Benga seemed to divine this by instinct and straightaway began to talk in his native tongue. Hammans was not fluent, but could reply intelligibly, and now Ota and Max are inseparable.

At 5 yesterday morning the African awoke and bounded out of bed. Max’s room is next door and he went in to show the boy about the house. When Ota saw the bath tub he gave a cry of joy and plunged in head-foremost.

During his stay at the orphanage, however, Benga, a 23-year-old man, demonstrated a more than casual interest in the girls and women there, and was eventually sent to a farm on Long Island until 1909.

As soon as Ota saw Mr. Gordon yesterday morning he announced that he wanted a wife quickly. Benga saw Miss Upson, one of the nurses, walking in the yard and insisted on marrying her at once. There is no question about his affection for her, and it was with considerable difficulty that he was persuaded to delay the marriage for a few days.

In 1910 Ota was brought to Lynchburg, Virginia, by Hunter Hayes of the Virginia Theological Seminary and College, ostensibly to receive training as a missionary. While there he was baptized, his name was changed to “Otto Bingo,” and he met both W.E.B. Du Bois and Booker T. Washington.

The pygmy, who is learning the English language, wants to become qualified as a missionary before he returns and told Verner so. The Baptist Ministers’ association of New York, it is stated, intends to send Ota to the Virginia seminary in Lynchburg as soon as he gets a good hold on the English language. It is thought it will take about eight years to make a good missionary out of Ota.

Meanwhile Verner himself left the ministry and worked in Africa as an agent of Belgian King Leopold II until the Congo Free State formally became a colony of Belgium in 1908. Verner then took various clerical positions until landing a role as health officer for a company working on the Panama Canal. His role in Benga’s life appears to have diminished greatly after 1907.

Benga’s formal education in Lynchburg proved unsuccessful, and he instead spent much of his time in a nearby forest when he wasn’t working on a tobacco plantation. Then came World War I. Alone, without the means to return to the Congo or even a ship that would carry him given the difficulties of travel during the war, on March 20, 1916, at approximately 32 years of age, Benga built a campfire, removed the caps from his pointed teeth, and shot himself with a revolver.

To be forcibly captured in the wilds of Africa and to be brought to America somewhat similar to the manner in which the first Africans were captured, though not to be sold as a slave, was the experience of Otto Bingo, who sent a bullet through his heart here yesterday to put an end to a yearning desire to return to his people on the east coast of Africa. The young negro was brought to Lynchburg about six years ago by some kindly- disposed person and was placed in the Virginia Theological Seminary and College here, where, for several years he labored to demonstrate to his benefactors that he did not possess the power of learning and some two or three years ago he quit the school and went to work as a laborer.

After leaving the college he went into a colored home near the school and since that had earned a livelihood by working in a tobacco factory.

For a long time the young negro pined for his African relations and grew morose when he realized that such a trip was out of the question, because of the lack of resources. Finally, the burden became so heavy that he secured a revolver from the woman with whom he lived, went to a stable and there sent a bullet through his heart, ending his life.

Epilogue

One of the benefits of exploring a collection such as Readex’s America’s Historical Newspapers is the thrill of discovering something new. Because Verner was a native of South Carolina, The State newspaper based in Columbia, South Carolina, appears to have taken a special interest in Verner and Benga, as several excerpts above show. In its September 26, 1906, edition it published an interview by reporter Allan Nicholson in which Verner spoke candidly and at length of Ota Benga, their relationship, and the circumstances of the media frenzy that had descended upon them.

There are numerous and varying accounts of Verner’s intentions towards Ota Benga, also questions relating to Verner’s departure from the ministry, and his tenure in the employ of King Leopold II of Belgium. Also, there is the fact that Ota Benga seems to have been largely abandoned in his struggle to assimilate in America or to gain passage back to the Congo, by persons avowing Christian charity.

The following excerpt gives some indication that Verner did the best he could in challenging circumstances that he perhaps did not entirely foresee. There is much more to this interview, and the reader is encouraged to seek it out.

Soon after returning to New York I took the pygmy, whose name, by the way, is Ota Benga, to the Zoo, simply to show him the animals and other things. That’s how the whole trouble began, though when I took him there I had no idea of leaving him other than ‘the man in the moon.’ When Dr. W.T. Hornaday, the director of the Zoo, saw Ota Benga, he at once became greatly interested in him, and said, “Let me keep him for you. I’ll give him a job here--he can take care of the monkeys, and particularly these young chimpanzees you have just brought us, and have a room that is entirely separated from the monkey cages, and which until recently was occupied by a white keeper.” The plan immediately struck me as a good one, for I knew I had to spend quite a while in New York, and I also knew that under hotel etiquette in New York none of the first class hotels there, on account of Ota Benga being African, would allow him to stay with me. I had already consulted the police about the matter, and they had suggested placing him in a negro boarding house, but I was afraid to do that as the museum people might get hold of him.

We’ll end with Verner in his own words, in his book Pioneering in Central Africa, published in 1903 before the fame and notoriety, as he waxes eloquent on the extent to which African hospitality does indeed outstrip that proffered in America. The disparity the African natives noted in 1904 was real then, and perhaps persists even into the present day.

The presents consisted of many large gourds full of foaming palm-wine, baskets brimming with large clean peanuts, bunches of plantains and bananas, a string of fowls, and a basket of potatoes. They were put at my feet by the crowd who accompanied Kweta, each one saluting me in turn, and all of them beaming with smiles of pleasant greeting. Never in my life had I been made to feel so keenly the way in which the black people had so effectively turned the tables on this representative of the South, of the Anglo-Saxon race, of the prided hospitality of a land built up on the labor of slaves. Here was no race issue, no color line, no question of skin or ancestry. Here was simply primitive African nobility delighted at the chance to exhibit its best qualities. Here Central Africa put South Carolina to the blush by a hospitality never outdone, a reception which could not but bring up a painful comparison when I thought of the arrival of some of these same people on Southern plantations fifty years before.

For more information about Readex digital collections, please contact Readex Marketing.