The Pope's Stone, Part Two: The Bloody Bedini Background

[The Pope’s Stone, Part One discussed the theft and destruction of a block of marble sent by Pope Pius IX in 1853 to be placed in the Washington Monument, under construction on the National Mall in Washington, D.C. This Part Two recounts some inflammatory background to that embarrassing episode in American history in the form of the perilous visit of a Vatican prelate just before the destruction of the stone.]

The announcement of his upcoming visit was short and succinct, in no way foreshadowing the waves of bigotry, chaos, and violence, which over the following seven months would accompany his progress through America. Baltimore’s Sunof June 27, 1853 reported simply:

"Monsignor Bedini, Archbishop of Thebes, former Commissary Extraordinary of the Pontifical Government to the Legations, has left Rome as special Envoy of His Holiness to the United States. He is charged by the Holy Father to pay a visit to the government at Washington, and also to hold interviews with different Prelates of the Church in the United States, and to acquire the most exact information respecting the interests and condition of the Catholic Church in this country. After making as along a visit as may be of advantage in the United States, Monsignor Bedini will go to Brazil, where he is to reside as Apostolic Nuncio near that Government."

Gaetano Bedini was born on May 15, 1806 in Sinigaglia, Italy, also the birthplace of Pius IX, not far from the Adriatic. After his ordination in 1828, Bedini was awarded a Doctor Utriusque Juris (i.e. doctorate in civil and canon law) and became secretary to Cardinal Altieri, Papal Nuncio at Vienna. In 1846 he was sent by the Pope to serve as Apostolic Internuncio [a sort of junior ambassador] to the Imperial Court of Brazil, where in the words of J.F. Connelley

“[Bedini] distinguished himself by his unstinting work for the German immigrants…and by his popular pleas in behalf of the German workers, who were being brazenly exploited by their employers.” (Connelley p. 289)

After his return to Italy, Pius IX appointed him Extraordinary Pontifical Commissioner of the Four Legations—Bologna, Ferrara, Forli, and Ravenna. His years in Bologna and the other legations (in this case a term for provinces in the Papal States) were well received by the citizens because of his promotion of agriculture, aid to the unemployed, and support of local businesses, but the Nationalists saw him as an authoritarian minion opposed to the growing democratic movement. They regarded him as “a covetous gallant opposed to all liberal undertakings.” (Connelley, p. 290) Back in Rome in 1853, Bedini, having read the Acta of the Catholic Councils in Baltimore, Maryland, wrote to the Secretary of the Sacred Congregation of Propaganda Fide of the Vatican, to say how “greatly impressed [he was] by the liberty which the Catholic Church enjoyed in the United States; the zeal of the bishops and priests and the continual increase in the number of American Catholics.” (Connelley, p. 5) The Pope made Bedini the Titular Archbishop of Thebes (i.e., an honorary bishop of a diocese in partibus infidelium) and Apostolic Nuncio to Brazil. On his return trip to Brazil, it was arranged through diplomatic channels that Bedini would first stop in the United States to visit not only the Catholic hierarchy and communities in America but also the seat of government in Washington, D.C. Upon his arrival in the United States on June 30, 1853, Archbishop Bedini was welcomed by New York Archbishop Thomas Hughes. The Boston Evening Transcripta week later noted Bedini’s arrival with approbation but some slight hint of uncertainty:

“Archbishop Bedini, specially commissioned by His Holiness Pope Pius IX to pay a visit to our government at Washington, (with what specific purpose in view, if any beyond the mere interchange of official courtesies, we are not informed) has arrived in town….Archbishop Bedini, as we showed the other day, is a very distinguished dignitary of the Church of Rome, and his advent here at this time is looked upon as quite an event by the Roman Catholics.”

So far so good, but the mood would soon change. In observing that Bedini had visited President Franklin Pierce on July 8 in Washington, The National Eraof July 21, 1853 went on to ask what kind of man Bedini was and why he had come to the United States:

The charge made, or rather repeated by the former priest and revolutionary, Alessandro Gavazzi, was that Bedini had had the Italian poet and patriot Ugo Bassi tortured and handed over to the occupying Austrian forces who executed him. Although the charge was without any foundation, Gavazzi, who had arrived in New York a few weeks ahead of Bedini, followed the prelate throughout his American tour in order to stir up anti-Bedini feelings, calling him the “Bloody Butcher of Bologna,” and thereby anti-Catholic sentiment especially among the Know-Nothings. And he succeeded.

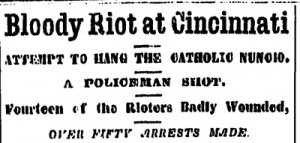

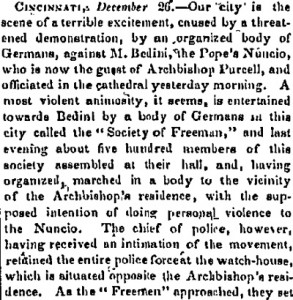

Bedini faced demonstrations against him in Pittsburgh as he had in other cities, including a planned assassination in New York thwarted by the police, before arriving in Cincinnati on December 21, 1853. Before he reached that city, the German-language newspaper Hochwächter also denounced Bedini, again describing him as “the Butcher of Bologna” and “urged its readers to avenge the injustice perpetrated by Bedini on the Italians.” (Endres, p. 8 ) On Christmas night at 10:30 p.m. some hundreds, according to some accounts over five hundred, of German-Americans and others, led by the German Society of Freeman, marched on the Catholic Cathedral in Cincinnati. Bearing an effigy of Bedini with a mitre on his head, a scaffold, and signs reading “Down with Bedini,” “No Priests, No Kings,” and so on; they headed toward the Cathedral and its neighboring episcopal residence. The city police, who had been made aware of the plan of the attack earlier that afternoon, rushed from their watch-house a little north of the Cathedral. As demonstrators confronted police, a shot rang out and a melee ensued. By the time it was over, “one protester was killed, fifteen were wounded, and sixty-three were arrested.” (Endres, p. 8 ) The Cleveland Plain Dealerof December 27, 1853 reported the events with a large-point headline reading “Bloody Riot at Cincinnati. Attempt to Hang the Catholic Nuncio. A Policeman Shot. Fourteen of the Rioters Badly Wounded...”

News of the Cincinnati riot, the word as used at that time was a synonym for what we would call a mass demonstration, was reported around the country, including in the Washington, D.C. Daily Globeof December, 28, 1853:

And how ironic that Bedini, who had championed the oppressed German immigrants in Brazil a decade before, should be so assaulted by German immigrants in Ohio less than a decade later! In fact, in the Readex digital collection of America’s Historical Newspapers one can find more than 260 articles dating between 1853 and 1854 on Bedini and his mission. A few weeks later the good citizens of Cincinnati burned a life-size effigy of Gaetano Bedini, as reported in New York’s The Weekly Heraldof January 21, 1854:

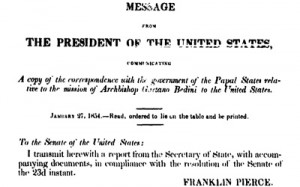

A national outcry after the Cincinnati riots led, not surprisingly, to a debate in the U.S. Senate on January 23 and 24, 1854, about Bedini, the protection of foreign dignitaries, and the nature of Bedini’s mission. Senator Lewis Cass of Michigan introduced a Resolution

“That the President of the United States be requested to communicate to the Senate, so far as he may deem it compatible with the public interest, a copy of any correspondence with the Government of the Papal States touching a mission to the United States.”

Senator Edward Everett of Massachusetts agreed with Cass, but Senator Stephen Adams of Mississippi argued that there was no reason for the Federal Government to have intervened in the Bedini incident because the individual states had their own laws. Senator Cass, whose son happened to be the American Minister to Rome, countered that the diplomatic status of Archbishop Bedini was precisely the point at issue. Senator John B. Weller of California represented the opposing view, interrupted by so much applause from Know-Nothings in the gallery that the President of the Senate had to call for order, and pleaded that

“The assembly that took place in Cincinnati was such a one that very often takes place in this country. I trust there will never be a power to prevent people from a free expression of their sentiments…” [For the whole debate, see the Congressional Globe, 33rd Congress, 1st Session, pp. 223-227 which is available digitally from the Library of Congress here.]

Nonetheless, in spite of the opposition of a few Senators and the gallery outbursts, the Resolution passed. Here, from the U.S. Congressional Serial Set, is President Pierce’s response to it.

The fact that the State Department inconveniently lost the diplomatic correspondence from the Vatican Secretary of State regarding Bedini’s mission both complicated matters and, in one reading, allowed the Federal government to deny any culpability for failing to grant Bedini diplomatic protection. In apparently seeking to apologize for the United States, New York’s The Weekly Herald of January 28, 1854 made a distinction between the classes of people responsible for Bedini’s ill treatment; namely “ignorant boors” [largely German and Irish] and “philosophic revolutionaries” as opposed to upright native-born Americans.

And yet, like Senator Weller, not all Americans were outraged by the treatment Bedini received here in the U.S. The Citizen, a New York City newspaper yet to be digitized, argued in its January 14, 1854 edition that:

“All citizens have a perfect right to burn any man of straw, and otherwise recreate themselves, express their partialities, and exercise their most sweet voices.”

Apparently riot and mayhem notwithstanding! About the end of his ill-fated and much misunderstood mission to the United States, Endres wrote:

“Since it was feared that the Italians might incite violence at the time of Bedini’s departure from New York on February 4, 1854, the Nuncio was secretly transported by way of rowboat to the steamship on which he would depart for Europe.” (Endres, p. 11)

Almost precisely a month after Bedini’s secret departure from New York harbor, the Pope’s stone was stolen from the Washington National Monument site and destroyed by a small band of Know-Nothings, not necessarily German-Americans from Cincinnati but men of similar anti-Catholic and anti-papist persuasion. Of course, in the sad case of Bedini one can see, in addition to religious animosity and definite American confusion between Church and State in Europe, an admixture of real political animosity, ignorance, and fear—but that is no excuse. Sources: the primary monographic source for Bedini’s visit is the 1960 Gregorianum University dissertation The Visit of Archbishop Gaetano Bedini by James F. Connelley (Analecta Gregoriana, vol. 109, Series Facultatis Historiae Ecclesiasticae, sectio B, n. 20), which relies heavily on Vatican archives but does not cover all the newspaper sources now available electronically and digitally searchable. See also the article “Know-Nothings, Nationhood, and the Nuncio: Reassessing the Visit of Archbishop Bedini” by David J. Endres in U.S. Catholic Historian, vol. 21, 2003; and the 1856 work The Catholic Church in the United States by Henri de Courcy de Laroche-Héron, a correspondent for Univers and other French Catholic periodicals, who was a confidant of Bedini.