“We hope that henceforth we will be able to obtain our rights”: Native Political Pressure in the Nineteenth Century

This is the fourth in a series of blog articles highlighting primary source content from the Readex Native American Tribal Histories collection. The articles in this series offer further insight and added perspectives into westward expansion, the Trail of Tears, the history of Manifest Destiny, and the impacts to Native Americans.

While wars, depredations, and massacres remained a fixture of Native-U.S. relations in the 19th century, Native tribal nations also asserted their rights through political means whenever possible. This blog will explore the three main demands/requests made by Native tribes: assertion of their sovereignty or rights; requests for more money or changes to annuities; and complaints of depredations by whites. It is useful to remember many of these demands were accompanied by the implicit threat of war should the United States government ignore them for too long.

The most fundamental request which Native tribal leaders made was the assertion of their sovereignty and rights.

In late February of 1841, a group of Cherokee leaders arrived in Washington, D.C. and remained there until at least September 20, when President John Tyler wrote a letter to them, acknowledging their efforts at “urging upon the government the consideration of the claims, the wishes and the grievances of your people."[i]

There is no indication in the text which event precipitated their journey or long stay, but Tyler made several broadly friendly promises to them, writing,

So far as it may be in my power to prevent it, you may be assured that it shall not again be said that a Cherokee has petitioned for justice in vain. I have looked over the several treaties that have been made between the Cherokee nation and the United States: and I find there promises of friendship on the one part and of protection and guardian care on the other; and I now again promise you, and through you, your whole people, that the protection and care so promised shall be given.[ii]

President Tyler made no specific promises of policy or indications of what steps might be taken to address the grievances of the Cherokee delegates, but their long stay indicates the persistence with which Native groups pressured the United States government to honor its promises. In June of 1846, several Cherokee leaders again asserted their rights to the U.S. government. In a letter to William Armstrong, the local Indian Agent, they wrote,

It is proposed to the undersigned who represent (and who alone represent) an organized Government to submit to the arbitration of a Commission in the organization of which they are to have no participation, questions involving the very existence of their Nation amongst other things the division of their Country and the extension over it of the Criminal laws of the United States.[iii]

The Cherokee protested their exclusion and warned,

Measures which they repeat in all truth and solemnity that they believe will be fatal to their Country and people and to which every man in the Cherokee Nation of all parties is opposed. If such measures shall be forced upon them which they do not and will not anticipate. It is due to themselves to their Country and posterity that the Undersigned should have no participation in it nor any share of the responsibility.[iv]

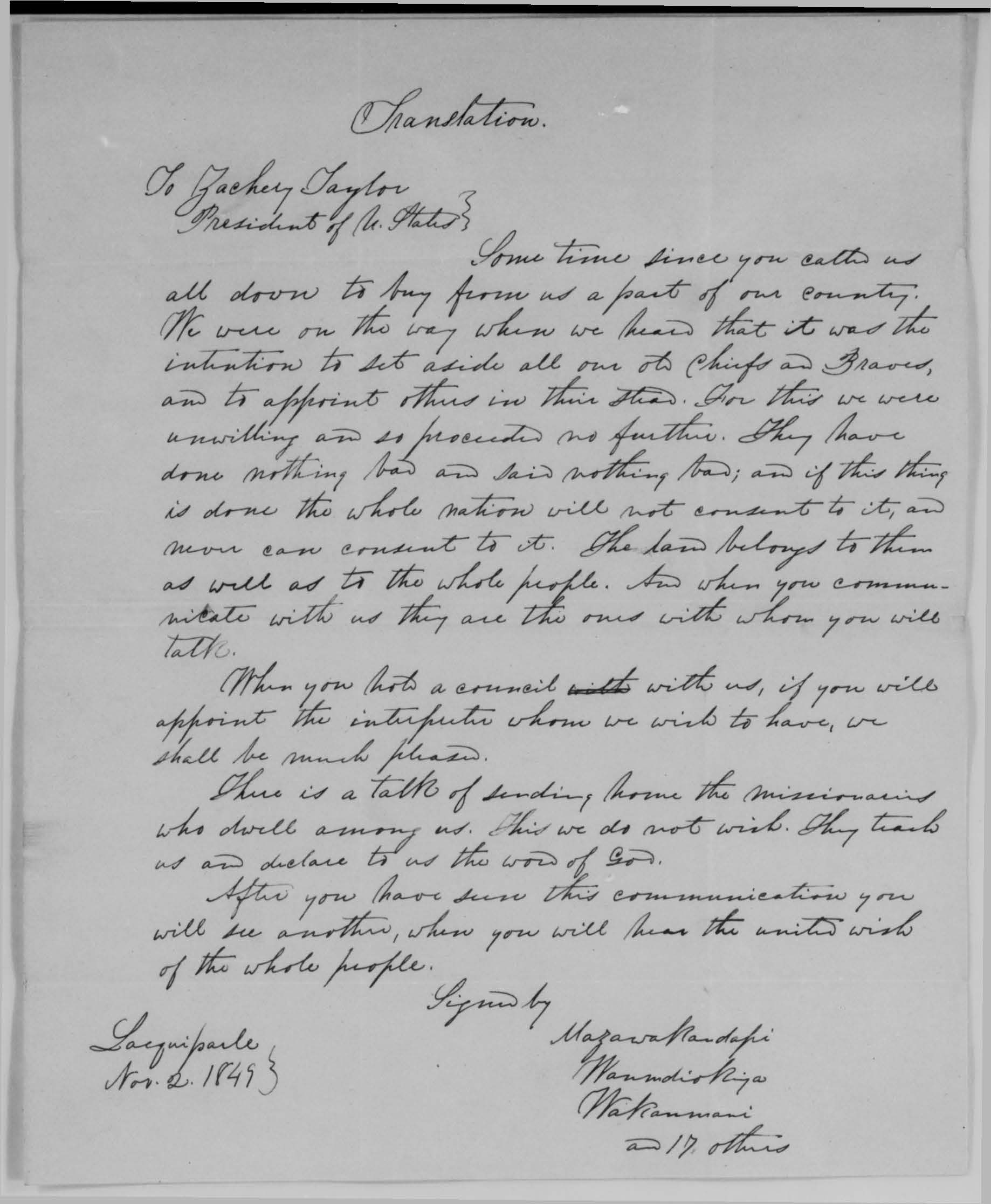

In November 1849, the Dakota had been on their way to negotiate with the United States to sell a portion of their territory, but refused to travel farther unless their demands were met. Several Dakota leaders at Lac qui Parle wrote to President Zachary Taylor to protest,

...the intention to set aside all our old Chiefs and Braves, and to appoint others in their stead… They have done nothing bad and said nothing bad; and if this thing is done the whole nation will not consent to it, and never can consent to it.[v]

In addition to keeping their own leaders, they also required “the interpreter whom we wish to have…” and to keep “the missionaries who dwell among us.”[vi]

In July of 1869, the Duwamish wrote to Ely S. Parker, the Commissioner of Indian Affairs, shortly after he took office. Greeting his appointment with optimism, the tribal leaders also shared their concerns and grievances, having a clear understanding of their rights and how they'd been denied annuities, goods, and money by previous agents:

It is true that at every change which took place among the Superintendency and Agents we had some hope that our unhappy condition would finally be changed into a better one, but we were often deceived in our expectations…The change which took place lately has been for us a subject of joy; we hope that henceforth we will be able to obtain our rights.[vii]

The Duwamish also warned Parker,

We the undersigned write to you to day to show you how we have been wronged, and to tell you that such conduct towards us has entertained in our heart a feeling of contempt and even of aversion for the whites.[viii]

We have begged the assistance of the physician for our sick people but it was refused to us. We are afraid that the whites will come to take away our valuable timber, and unless the lines [of our territory] are clearly described they would certainly do so.[ix]

They appealed to Parker for the concessions and annuities which had been set aside for them in their treaty.

While Native Americans were often characterized by Indian agents as childlike and unfit to manage their own affairs, many tribes took an active role in the allocation of their annuities.

In October 1849, the Winnebago wrote to President Zachary Taylor, “When we moved to this country certain stipulations were made with us and we think they have not been fulfilled.”[x]

The letter went on to enumerate a numbered list of payments which had been promised but had never materialized; $20,000 as payment to remove from their old territory, $20,000 to fund the removal itself, $20,000 in appropriations from the old treaties “for Blacksmith Shop, Farming, School and mill…”, and under the treaty of 1846, an additional $25,000. The Winnebago stated:

Our agent has refused to pay us the money under the 1st and 2nd articles above as was stipulated in the Treaty – our provisions which our Great Father sends us from year to year are not received, The provisions which our agent has purchased for us he has squandered. We have signed receipts to the agent for the money for these provisions upon his promise to purchase them.[xi]

The Delaware wrote to Enoch Hoag, the Commissioner of Indian Affairs, in 1874 in a bid to change the way their annuities were distributed. They petitioned for the surplus money which “was turned over to the Chiefs, and is by them used for Sectarian and Private uses.”[xii] They asked that in the future, all money should be paid out to the tribe, and emphasized:

There are among our tribe a great many Widows and Orphans that are in a destitute condition, and precarious circumstances and are in great need of all monies due them, to keep them from actual suffering.[xiii]

In August of 1874, a council of the Osage petitioned Enoch Hoag for special appropriations totaling over two hundred thousand dollars. They requested $51,037.45 to be distributed almost immediately for fall 1874, and an equal amount the following spring. $60,000 was requested for building purposes,

Thirty thousand dollars to be used in support of Agency and Sawmill including in the Salaries of Mechanics, Laborers and all Employees at and around Agency and mill, eight thousand to be in use for National Council purposes,

And

...that our Agent provide for the support of two Portable Saw Mills in pay for Lumber the price not to exceed Fifteen Dollars ($15.00) per thousand feet, to be used for the benefit of Citizens of our Nations and that three thousand four hundred and fifty six Dollars $3456.00 be expended for Educational purposes.[xiv]

While it was not uncommon for Indian agents to attempt to enrich themselves at the cost of the Native Americans under their authority, this petition was signed by over thirty leaders of the Osage Nation, who wrote,

We beg this increased amount of money Payment as a necessity, for in consequence of the prevailing drouth [sic] this year and our light summer hunt we shall be left with small means of support. We beg it too on account of the insufficient amount of our past Payments, having always been unable to provided for all the necessary Goods and Provisions, and making it ever compelling for us to receive advances from Stores, on our Annuity long before we are paid.[xv]

Their request does not appear to have been granted, because the Osage wrote again in January 1875 to ask for appropriations of $75,000.

According to the accompanying letter written by Isaac T. Gibson, the local Indian agent, “their appropriations were nearly exhausted.”[xvi]

The petition from the Osage asked for:

...funds to be used during the present fiscal year under the direction of the Secretary of the Interior in paying us a semi annuity in the Spring of fifty thousand dollars, for a portable saw mill for the building and completion of Houses, opening farms, purchase of Wagons, farming implements and tools and for other beneficial purposes.[xvii]

Like the previous petition, the letter was signed by over two dozen Osage officials.

David Geboe, chief of the Western Miami, wrote in May 1875 to Edward Parmelee Smith, the Commissioner of Indian Affairs, about “the unsettled condition of my people.”[xviii] Geboe’s tribe had recently removed from their old territory to a section of the “Confd [Confederated] Peoria &c Reservation,” but the Miami still owed money to the Peoria for the land on which they had settled. He wrote,

Our Peoria brothers are very much dissatisfied at the delay in our paying them, what they consider their just dues, and this is engendering bad feeling between the two tribes who should live together, in peace and harmony. And among my own people, the uncertain and precarious tenure, by which we hold our homes, on which by the advice of the Department we have many of us valuable improvements, tends to dishearten many, and keep them from making improvements.”[xix]

He asked Smith to use his influence to make sure the debt was paid soon,

as the faster they [the Miami] make improvements on their lands, the sooner they will become self supporting, and independent of their annuities, ‘which is a consummation devoutly to be wished.’”[xx]

The Commissioner responded just ten days later, but the news was not favorable. Smith wrote,

…the Department prepared, and presented to Congress at its last session, a bill looking to the adjustment of the affairs between the Miamies [sic], and the Kaskaskias [sic] &c, but upon which for some reason unknown to this Office, that body took no action.”[xxi] In the absence of special legislation in the premises, the Department has no legal authority, to take any steps…

Smith promised,

This office will however use its influences, in securing the necessary legislation at the next session of Congress, in order that the consolidation of the tribes named may be effected, in accordance with their wishes…[xxii]

Tensions between settlers and Native communities often ran high, and thefts or violence on both sides was common. While whites often demanded repayment from the government for the damages caused by these incidents, Native groups sometimes did the same.

In a letter to Enoch Hoag, Superintendent of Indian Affairs in the region, Delaware leaders James Connor and Charles Journeycake wrote, “In accordance with your instructions we hereby forward to you the following discribed [sic] claims of the Delaware Indians against the U.S. Government.”[xxiii]

The letter included an itemized list of grievances, including,

...thirty thousand dollars for Depridations [sic] on timber…

$14,729 for the twenty three sections of land known as the half Breed Kaw lands…

$26,284 for Stock stolen from the Delawares by whites…

$28,959.41 Damages and right of Way of K.P.R.W. [Kansas Pacific Railway] acrost [sic] the Delaware Reserve which is the amt allowed by parties appointed by the Govt…

And several claims for land, including,

...the value of the Fort Leavenworth Reservation… We can fix no specific value upon this claim but in justice to the Indians we think the Govt. should pay us something for it.[xxiv]

Many of these claims were supported by treaty articles, which Connor and Journeycake also cited. Lastly, they expressed some frustration over the Bureau’s inaction;

...we have furnished the statement several times and no action having been taken upon it we hope that you will put it into hands that will attend to it and persecute the matter to a final settlement.[xxv]

While Native American rights and sovereignty were often ignored, and were progressively eroded by U.S. governmental policy, Native nations continued to assert them in any way they could.

[i] [Letter from President John Tyler and Albert Miller Lea to Chief John Ross and Delegates of the Cherokee Nation, Sept 20, 1841]

[ii] Ibid.

[iii] [Letter from Cherokee Nation Delegates to William Armstrong, June 26, 1846]

[iv] Ibid.

[v] [Memorial from Dakota Indians at Lac qui Parle to Zachary Taylor, Nov. 2, 1849]

[vi] Ibid.

[vii] [Letter from Iatab Wakletchow and Phillip Seattle to Ely S. Parker, July 5, 1869]

[viii] Ibid.

[ix] Ibid.

[x] [Memorial from Winnebago Indians to Zachary Taylor, Oct. 27, 1849]

[xi] Ibid.

[xii] [Letter from Members of the Delaware to Enoch Hoag, July 27, 1874]

[xiii] Ibid.

[xiv] [Letter from Isaac T. Gibson to Edward P. Smith, Aug. 20, 1874]

[xv] Ibid.

[xvi] [Letter from Isaac T. Gibson to Edward P. Smith, Jan. 14, 1875]

[xvii] Ibid.

[xviii] [Letter from Hiram W. Jones to Edward P. Smith, May 6, 1875]

[xix] Ibid.

[xx] Ibid.

[xxi] [Letter from Edward P. Smith to Hiram W. Jones, May 15, 1875]

[xxii] Ibid.

[xxiii] [Letter from James Connor and Charles Journeycake to Enoch Hoag, Jan. 21, 1875]

[xxiv] Ibid.

[xxv] Ibid.

Other blogs in this series:

- Part 1: Native Removal Prior to the Indian Removal Act of 1830

- Part 2: Nineteenth Century Treaties with Native American Nations

- Part 3: “For the Great Father is angry, and will certainly hunt them down…”: Native American Wars Against United States Expansion

Visit the Readex Native American Tribal Histories page for information on this collection and to request a complimentary trial.