American Underworld: The Flash Press offers rare glimpses of women's place and presence in nineteenth-century northeastern American cities. The digital collection is particularly rich in evidence of women as entrepreneurs, entertainers, and consumers of goods and cultural products. Cultural historians and literary scholars will also find fictional women across the database, with women appearing in serialized stories as sweethearts and wives, mothers, victims of crime, and working women.

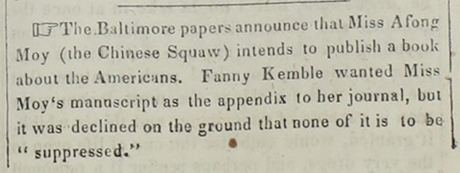

It is well worth noting that the women represented in the pages of these newspapers are, overwhelmingly, white. Black women appear infrequently in news of criminal activities or as contemptible stereotypes of black womanhood. One brief but notable reference to a non-white woman is a small item in an 1835 edition of the Albany Microscope: Afong Moy, a Chinese woman who made a career out of speaking and performing before American audiences, was planning to write a book about the American people.

American Underworld has particular value for uncovering the histories of economically independent women in northeastern cities, demonstrating the limited range of economic opportunities available to them in the nineteenth century. Prostitutes and brothel keepers appear more frequently in the database than women in any other occupation. While their presence in urban life is already well documented by historians, the richness of detail in the flash and racy press allows for more nuanced historical study. Researchers will find them by looking for poetic euphemisms, including “the frail sisterhood” and “nymphs of the pave.”

While the collection is obviously useful for illuminating socially transgressive activities like sex outside of marriage and criminal acts, it also has surprising value for discovering more ordinary lives. Most often, women who advertised in the flash press built their businesses on skills associated with domestic work. For example, through an 1848 advertisement in the National Police Gazette we learn that Mrs. Souder of New York City offered a service traditionally provided by wives and mothers, hand-sewing shirts for men.

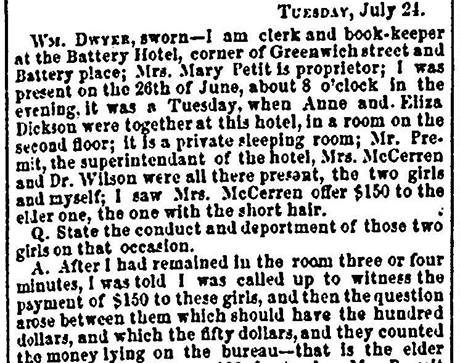

Operating boarding houses was a common nineteenth-century livelihood for independent women. The practice allowed women to commodify the domestic skills that they were trained for and filled a significant demand in rapidly growing commercial cities. Examples from American Underworld include an 1842 advertisement in the Whip, and Satirist of New-York and Brooklyn announcing that Mrs. Weeks operated a boarding house at 187 Chatham Street in New York City; trial transcripts published in the National Police Gazette in 1849 reveal that Mrs. Mary Petit was the proprietor of the Battery Hotel.

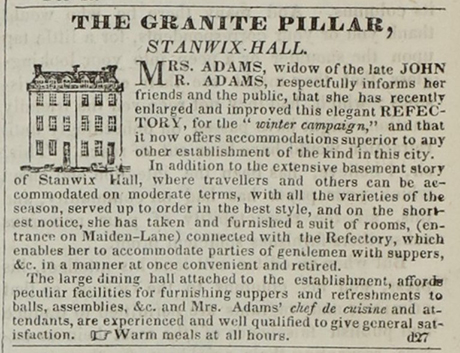

Educated women sometimes opened schools. In 1839, as seen in the New York Evening Signal, one Miss Jackson operated a boarding school for “Young Ladies” in which she provided advanced training in French, Music, and Drawing along with “all the comforts of a genteel and quiet home.” While women-owned restaurants appear to have been relatively uncommon in nineteenth-century urban America, in 1835 a widow, Mrs. Adams, advertised in the Albany Microscope the addition of private dining rooms to her “elegant Refectory,” promising that hers was “superior to any other establishment of the kind in this city.”

In these records, we also find women who offered more idiosyncratic services, such as those provided in the 1840s by the entrepreneurial “Philosopher, Physiognomist, [and] Phrenologist” who called herself Madame Adolph.

For fifty cents, as seen in the 1848 National Police Gazette ad below, Mrs. Roeder of New York City would draw on her professional knowledge of “Phrenology, Astronomy, Palmistry, and Science” to “answer all lawful interesting questions.”

Theatrical announcements and reviews tell us something about nineteenth-century actresses and dancers. Some are still well known to historians and aficionados of dance and theatre history, including actresses Fanny Kemble, Charlotte Cushman, Laura Keene, and Ellen Tree. Other performers, now forgotten, include Miss E. Wheatley, whom the Albany Microscope praised in 1834 for her perfect imitation of Fanny Kemble. In 1842, the Whip, and Satirist of New-York and Brooklyn announced Mrs. Thorne’s performance as Selema in “the splendid Drama of Mazeppa,” a role that later made Adah Isaacs Menken a world-renowned star. Some of the newspapers in American Underworld also report on theatrical news from abroad. A March 1840 edition of the Evening Signal reported that the “departure of Fanny Elssler” from the London stage was reportedly “regarded as a great calamity, for who can replace her?”

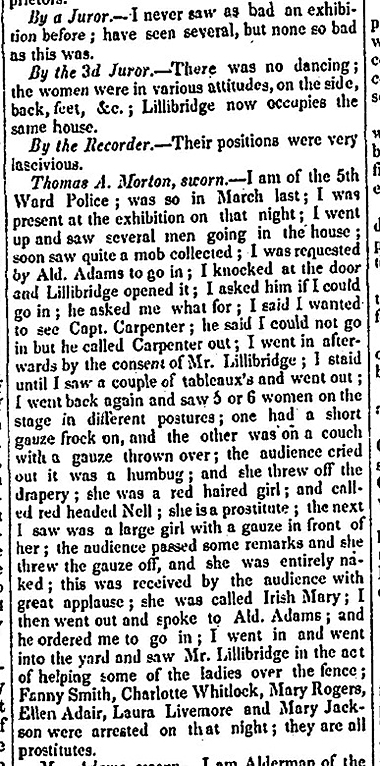

Readers can also find evidence of the women who earned money performing as “Model Artistes,” posing on stage in short, sheer tunics or entirely nude, in various static poses. The National Police Gazette of June 10, 1848 reported on a court trial about one such show that took place earlier that year at the Eagle Hotel on Canal Street in New York City. Several women are named in the account, and these records provide all-too-rare information about them. The article noted, for instance, that Laura Livemore was among those who testified in the case. Described as “a tall girl dressed in a calico frock, green hat, a black shawl” and apparently “about 26 years of age,” she told the court that she was paid $3 for the performance.

Women arrested and convicted of crimes, including pickpockets and the occasional “murderess,” make regular flash press appearances in police court reports, trial transcriptions, and sensational accounts. The New Hampshire Telescope, for instance, reported the arrest in 1848 of a woman named Hannah P. Neal, for stealing twelve dollars in cash and the purse that contained the bills. Transcribed court testimony also preserves women’s voices as witnesses to crimes and reveals rare evidence of the lives of women who were victims. This digital archive suggests that the most common criminal dangers to women included being “seduced” and tricked or even sold into sexual servitude, sexual assault, and domestic violence, including murder.

American Underworld: The Flash Press reveals women in mercantile trades and demonstrates male merchants’ awareness of women as consumers. Across the collection, ads offer fabrics imported from England, Scotland, and France, along with hats, veils, gloves, hosiery, and, occasionally, ready-made garments, including “Grand Fancy Ball Dress.” In 1840, the milliner Mrs. Mein of New York City announced the arrival of bonnets, flowers, and ribbons from Paris, all in the latest style. In the same year, one Mrs. Friend advertised her “wholesale and retail curl store [and] ornamental hair manufactory” on Grand Street in the same city. A shop at 411 Broadway in New York City advertised a range of goods for women, including “Ladies’ pocket-books and Thread Cases…wrought of Pearl, Ivory, and Morocco.”

In 1840, the New York Evening Signal featured an advertisement for the “Fancy Dealers,” Tiffany and Young, addressed “To the Ladies.” Offerings included the latest fashion in “French Fancy Note Papers” and other epistolary supplies. A simple 1849 advertisement in New Hampshire’s Manchester Telescope offered accessories for women, including “Parasoletts,” visites (a type of short coat worn by women), and silk fabrics, while the shop of E. G. Collins carried “Bonnets, Ribbons, Laces, Artificial Flowers” and “Millinery Goods of Every Description.” An 1852 advertisement in the National Police Gazette for Brown & Tasker’s dry goods emporium lists no fewer than nineteen different types of hair combs, ten types of fans, and a variety of consumer goods: brushes, beads, buttons, needles, perfumes, soaps, various knives, and a range of “fancy goods,” including “pocket books and portemanteaus” [sic].

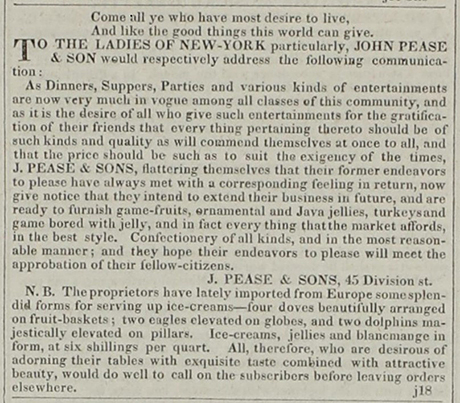

Specialized products were marketed to mothers and housewives as well. For instance, Tuttle’s patented baby jumper, similar to a device that is still available today, was advertised in the flash press of Boston, Philadelphia, and New York in 1848 as “one of the most truly labor-saving inventions of the age.” In the same year, Thomas Hobson of New York City advertised in the National Police Gazette a “Ladies [sic] Delight,” a “newly invented” washing machine that would allegedly wash clothes “perfectly clean” in just three minutes. In a detail that tells of very different attitudes towards children, the ad claimed that the device was so simple to operate that it “could be worked by a child with ease.” In 1852, I. M. Singer advertised his new and improved sewing machine, which had been patented the previous year. The confectioner John Pease of New York appealed particularly to middle- and upper-class women who wished to impress their dinner guests, offering in 1840 the latest fashion in “confectionery of all kinds” along with “splendid” vessels for serving one of the latest urban food crazes, ice cream.

Product advertisements in the flash press also promised women improved beauty and health. Dr. Townsend’s wonder cure promised to improve women’s beauty by giving them “elasticity of step, buoyant spirits, sparking eyes, and beautiful complexions.” Dr. F. Felix Gouraud’s Poudres Subtiles for Uprooting Hair promised mustachioed women yet another way to improve their attractiveness. Women who suffered from a prolapsed uterus could visit Dr. Hull’s office in New York to purchase his Utero-Abdominal Supporter; to insure their privacy, the doctor set aside special “Ladies’ hours” from noon to 2:30 pm every day. Dr. Townsend’s Sarsparilla claimed to cure a wide range of ailments particular to women, including the symptoms of “the turn of life” (menopause). It also promised, improbably, to cure both infertility and “obstructed…menstruation,” a euphemism for pregnancy—that is, it supposedly acted as an abortifacient.

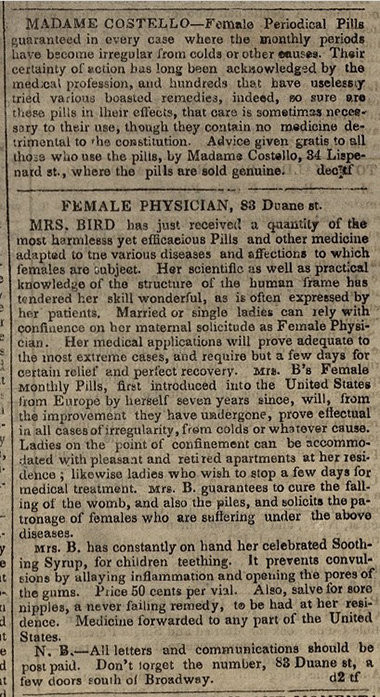

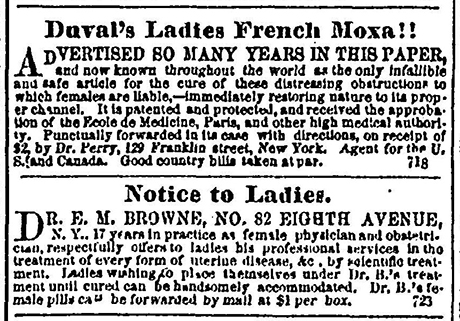

Self-trained women “physicians” appear in the pages of the flash press, specializing in treating pregnant women, providing abortion services, and healing women who had sexually transmitted diseases. The women who worked as abortionists under the professional names Madame Restell and Madame Costello are already known to historians. Less well known, however, are women like Mrs. Bird, who operated in 1842 New York as a “female physician.” As seen in this advertisement from the Whip, and Satirist of New-York and Brooklyn, she was a purveyor of abortifacients and a “soothing syrup” (an opiate, perhaps) to calm teething children.

Male abortionists also advertised, promising remedies for “every form of uterine disease,” including “those distressing obstructions to which females are liable,” a euphemism for pregnancy.

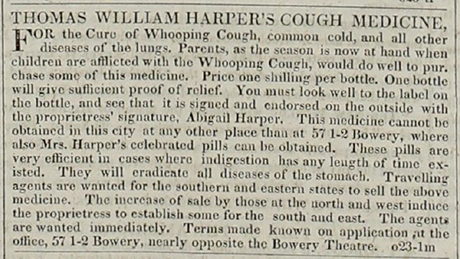

At a time in which women’s home remedies were far more common treatments than professionally trained doctor’s services, some entrepreneurial women peddled their own formulas as well as medicines produced by men. In 1839, Abigail Harper operated a shop in lower Manhattan where one could purchase her “celebrated pills” for indigestion, along with a cough medicine named for her husband but bearing her own signature across the label. In the 1840s and 1850s, Mrs. Hays of Brooklyn sold a variety of purported cures, including Comstock’s Magical Pain Extractor and Bush’s Renovating Aromatic Cordial.

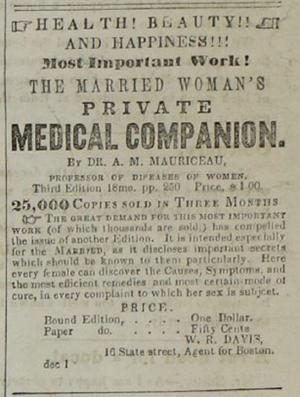

In an age in which sexual knowledge was a taboo subject, particularly for women, an 1848 advertisement in the National Police Gazette marketed Every Mother’s Book to “every married person.” The book, subtitled, “the Duty of Husband and Wife physiologically discussed,” appears to have provided information (whether spurious or not) about birth control, the better to prevent “the terrors of poverty, and the prospect of a family children which could be but poorly reared.” Similarly, in 1850, the Married Woman’s Private Medical Companion promised similar information about both birth control and abortion.

American Underworld provides evidence of women engaged in other activities in urban public spaces. These include a few women lecturers who participated actively in the marketplace of nineteenth-century ideas in spite of widespread criticism of their boldness. Woman’s rights advocate, health reformer, and writer Mary S. Gove (later Nichols) is among the most significant historical figures to appear in the database. Her insistence that women should be educated about their bodies set her apart from most other American reformers. The Evening Signal in 1840 praised her as “one of the most extraordinary females we ever happened to meet with,” while excoriating similarly radical and outspoken women reformers, including Mary Wollstonecraft and Frances Wright.

The flash press also sheds light on women's enjoyment of popular leisure-time activities that were available in nineteenth-century New York City. At a time in which women of the middle- and upper-classes could not socialize with men in public and still be considered respectable, a few male entrepreneurs created segregated opportunities for women to participate in the attractions that were available to men. Amid debates about whether women should be protected from knowledge of the human body, in the 1840s the Anatomical Museum in New York City set special hours during which only ladies would be admitted. A New York City restaurant run by owners Frazee and Mapes informed readers of the National Police Gazette in 1852 that it provided a “ladies saloon” [sic] in which “ladies unaccompanied or accompanied by gentlemen” could enjoy breakfast, lunch, and dinner.

In using American Underworld to better understand women's experiences and the significance of those experiences, it is important to remember that in the flash press, women rarely speak for themselves. The evidence of their presence in public and the meanings of that presence were interpreted by men. Still, through these sources, we can begin to sketch out women's place in urban life and better understand the significance of their experiences and contributions to nineteenth-century American history.