African American Education and Postbellum Ambivalence: A Look at the Relationship between the Presbyterian Church and Lincoln University

As for intellect, all I can say is, if a woman have a pint and a man a quart—why cant she have her little pint full? You need not be afraid to give us our rights for fear we will take too much,—for we cant take more than our pint'll hold.

— Attributed to Sojourner Truth (June 21, 1851)[1]

This lesson plan will provide freshman-level college students with skills in using Afro-Americana Imprints, 1535-1922, a Readex digital collection, and with historical knowledge of impediments (sometimes unwitting) to the self-actualization of black peoples after the American Civil War. Most crucially, this unit is designed to make students aware of the ways in which the postbellum philanthropic and predominantly white Presbyterian Church demonstrated ambivalence about contributing funds to support Lincoln University. This all-black college is defined in the Presbyterians’ 1866 Annual Report as a “pioneer Seminary for the instruction of young colored men” (“Forty-seventh annual report”45). While freed black people strove to build schools for themselves and pursued other forms of self-actualization immediately following the Civil War, they nonetheless needed to rely on white wealth and philanthropy to develop institutions of higher education. Ultimately, as the 1882 Catalogue of Lincoln University later demonstrated, the white philanthropic Presbyterian support of Lincoln University exposed an ambivalence toward their own “humane efforts to elevate and improve this long-oppressed race” (“Forty-seventh annual report” 45). Arguably, the Presbyterian Church seems to have desired to act in accordance with Christian values, but they also seem to have both doubted black peoples’ intelligibility and feared an increase in black intelligence. Moreover, their investment in Lincoln made them a boon to the development of African American growth. The 1877 Reports of the Boards of the Presbyterian Church reveals that the philanthropists assessed themselves as morally and intellectually superior to the African Americans they sought to empower.

The Presbyterian General Assembly eagerly supported academic education for freed black people both before and after the Civil War (“Forty-seventh annual report” 45, 46).In fact, Lincoln was originally founded for black men in 1854 as the Ashmun Institute in Chester County, Pennsylvania, by the Presbyterian minister John Miller Dickey and his spouse, Sarah Emlen Cresson (“Lincoln University”).[2] Yet, three particular documents—the Catalogue of Lincoln University, “Forty-seventh annual report of the Board of Education of the Presbyterian Church in the United States of America; Presented to the General Assembly, May, 1866,” (both, found in Afro-Americana Imprints ) and The Reports of the Boards, Volume 4—indirectly reveal that northern postbellum whites often exerted excessive control over the development of instructional institutions for African Americans during the postbellum period. Littered throughout these texts, one finds such statements as “Lincoln University has special claims upon the benevolence of the Church;” “The friends of the education of ‘colored youth’ are cordially invited to investigate its plans and operations, and to cooperate with its officers in conferring the benefits of a liberal and Christian culture on those who prize and so much need this blessing;” and “The election of the Trustees is, as formerly, in the hands of the Presbytery of Newcastle, which, at its recent meetings, cordially chose a Board, in which there are representatives from several of the Evangelical denominations” (Reports of the Boards 567, Catalogue 31,“Forty-seventh annual report”46). These assertions suggest a strong, and potentially oppressive, white intervention. The Presbyterian General Assembly had genuine interest in education for black people, but these documents suggest this interest minimized African Americans’ collective ability to establish free-thinking academic institutions.

The establishment of academic institutions was a significant goal for African Americans because education could provide a foundation for the spread of intellectual ideas and economic advancement. Since education is vital for reaching economic self-determination on a large scale, black people of the postbellum period centered academics in their efforts at self-actualization, a term that involves “the individual’s capacity to function with independence and autonomy from others, to exercise his or her own will, and to act spontaneously in the ultimate search for personal identity" (Grabb and Waugh 215-16). The control that white Presbyterians wanted to exert over the founders and students of Lincoln University and other black groups suggests an ideological divide that threatened the self-actualization process.

The compiled “Reports of the Boards” reveals that while the Presbyterian General Assembly was dedicated to the education of African Americans, its members also show evidence of white supremacist notions. The General Assembly’s reports insinuate they believe themselves superior to African Americans. For example, they note that “The University [Lincoln] claims a peculiar advantage in the education of its students, from the fact of their being removed so far from the close association with their own race” (Reports of the Boards 567). This statement suggests two truths about the Presbyterian benefactors of Lincoln University. First, although there were black Presbyterians across the nineteenth century, the wealthy, mostly white Presbyterians who supported Lincoln University imply racialized distinctions between themselves and all black people, and a second gap between the African Americans populating Lincoln and their uneducated black kinfolk who threaten to have an “embarrassing influence” on them through dangerously “close association.” The Assembly’s pronoun “their” in the phrase “their own race” betrays a perceived racial difference. Second, the Presbyterian benefactors suggest they find it commendable that Lincoln’s black population lack close association with other black people who were uneducated, or not educated according to the academic ideals supported by the Presbyterians. Although some Presbyterians were African Americans, there is a racial division shown in the General Assembly notes that demonstrates the members’ white supremacist values.

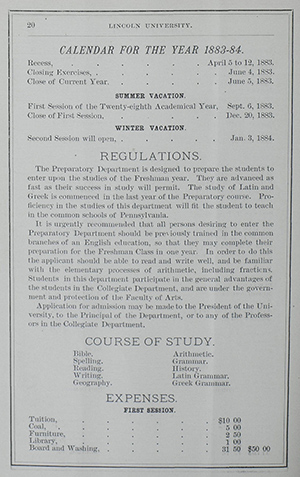

The “Catalogue of Lincoln University” will demonstrate to contemporary students that the postbellum Presbyterian Church supported the university as an important source of black self-actualization. The document connects Lincoln University with the Presbyterian Church by naming and quoting from one of its documents (Catalogue 25-26). The document further demonstrates a connection between these two institutions by acknowledging that the school, particularly the theology department, was “placed under the control of the General Assembly of the Presbyterian Church” (Catalogue 28). Particularly striking is that it provides coursework information on preparatory classes designed to get students who are behind academically up to the denomination’s collegiate standards. Rather than building an institute for the “elite” of black society, the trustees were apparently attempting to be as inclusive as possible: “The Preparatory Department is designed to prepare the students to enter upon the studies of the Freshman year. They are advanced as fast as their success in study permit” (Catalogue 20). The existence of a preparatory department reveals the university attempting to facilitate African American self-actualization by providing an avenue for students to accelerate the acquisition of foundational skills and knowledge, especially those students who did not yet have the tools necessary to compete in a more rigorous academic setting.

The three documents used in this course unit were produced in a span of almost two decades of each other, and reveal that the Presbyterian Church had ideals and goals not necessarily conducive for black self-actualization. These ideals were exerted through funding. For example, the “Catalogue of Lincoln University” demonstrates that the Church sought to assess and control students’ conduct and behavior. The catalogue states, “[E]very applicant for admission must present evidence of good moral character” (6). But the benefactors apparently considered themselves the best, if not exclusive, judges of “good moral character.” In “The Minutes of the General Assembly” the members tacitly assert their ability to discern morality: “There is real danger that the leaders of the Freedmen, infected with the weakness of indiscriminate sympathy, should excuse and tolerate, in others and themselves, abuses which require immediate rebuke and correction” (Reports of the Boards 628). This sentence demonstrates white supremacist sentiments, despite the General Assembly’s philanthropy. Furthermore, the Presbyterian Church expressed its concern with Lincoln students demonstrating “good moral character,” but it does not indicate a comparable concern with the character of white students.[3] Also, what would have stopped any persons from giving false witness towards a student who crossed them? Perhaps it is not too much to suggest that one of the basic requirements of admittance to and continued study at Lincoln University was that black students accept being placed in a vulnerable and dependent position in which they had little power relative to the benefactors’ white supremacy.

Using the specified documents,[4] the instructor should facilitate class discussion so that students understand various impediments to postbellum African Americans’ efforts to determine their own futures. Because the intentions of newly freed African Americans and their wealthy white supporters were apparently divergent, class discussion should illuminate the difficulties postbellum African Americans faced in trying to receive an education, and the complex attitudes of white benefactors who, due largely to their own ingrained social and historical constructs, inadvertently impeded rather than fully fostered black self-actualization.

Objectives

- To understand that education is a resource crucial to self-actualization

- To consider racialized, (post) colonial subjects’ resistance to white, hegemonic forces, as described by Toni Morrison and Gayatri Spivak[5]

- To analyze “Catalogue of Lincoln University” and Reports of the Boards, Volume 4

- To discuss the relationship between postbellum white philanthropy and African American self-actualization.

Materials

- “Catalogue of Lincoln University,” available in Readex’s online collection Afro-Americana Imprints, 1535-1922

- “Forty-seventh annual report of the Board of Education of the Presbyterian Church” (1866), available in Readex’s online collection Afro-Americana Imprints, 1535-1922

- Reports of the Boards, Volume 4 by the Presbyterian Church

- PowerPoint can be developed to provide:

- a timeline that highlights social and legal impediments used by whites to obstruct postbellum African American political growth.

- short histories of several African American universities

- brief biographies of major African American education activists, including Anna Julia Cooper, W. E. B. Du Bois and Booker T. Washington

- information on nineteenth-century Presbyterian philanthropy

- Optional: online discussion board

Document Analysis:

This activity will provide students with a foundation to discuss the relationship between postbellum U.S. white philanthropy and black education. For this activity, the instructor can have students access the “Catalogue of Lincoln University” in Afro-Americana Imprints, 1535-1922. Students should analyze references to the Presbyterian Church in order to understand (white, Christian) funding for black education.

Student-Led Discussion

Researching the Afro-Americana Imprints, 1535-1922, students will develop a pros-and-cons list of the effects white philanthropy had on black self-actualization through education in the postbellum period. Students will then pick one pro or con to focus on in a five-minute discussion with the class on the implications of that pro or con.

Additional activities:

- Identify other white philanthropic organizations working toward education for the newly freed people between 1865 and 1885, and discuss their respective strategies used to achieve this goal.

- Identify postbellum black leaders and discuss the ways they exerted agency over their own lives and circumnavigated the social constructs that were designed to impede their success.

- Locate correspondence between African American leaders and white philanthropists about the development of after slavery.[6]

Additional Questions:

- Is there a clear difference between the goals of black people and white philanthropists in the document? If so, what are those differences?

- What are some factors that apparently complicate the relationship between white philanthropists and black groups pursuing self-determination?

- What types of influence do white philanthropists seem to have exerted over black people pursuing individual and collective education?

- How do various documents reveal the complex issues undergirding white philanthropic investment in black political development after slavery? (Consider a text’s rhetoric, authorship, audience, and so on.)

Conclusion: Understanding White Ambivalence

The key documents highlighted above demonstrate how white philanthropic Presbyterian support of Lincoln University expressed ambivalence towards an oppressed group they ostensibly sought to help. On one hand, the Presbyterian Church desired to aid black peoples’ education. On the other hand, their documents reveal white supremacist attitudes toward African American’s intellectual and moral capability. These conflicting ideals created an environment that was not necessarily conducive to the self-actualization efforts of African Americans, despite the fact that the philanthropic efforts allowed for educational opportunities that were necessary for the elevation African American communities.

Notes

[1] Nell Irvin Painter, "Representing Truth: Sojourner Truth's Knowing and Becoming Known," Journal of American History 81.2 (Sep. 1994): 461-492. Painter prefaces Truth’s thusly: “This is the report of Sojourner Truth's speech in Akron, Ohio, in 1851 as it appears in the Salem [Ohio] Anti-Slavery Bugle, June 21, 1851, reported by Marius Robinson” (488).

[2] Ashmun Institute was originally named for Jehudi Ashmun, a founder and the first governor of Liberia. It was changed to Lincoln University after the Civil War, in honor of Abraham Lincoln (“Liberia,” "Lincoln University").

[3] Lincoln University was among several universities the Presbyterian Church supported during the nineteenth century; it was the only university for African Americans. The report section on Lincoln references the importance of students’ good character three times in two pages. The report’s other sections, on the white institutions the Presbyterians supported (including Princeton and Washington and Jefferson College), contain no references to students’ moral character.

[4] Numerous documents in the Afro-Americana Imprints, 1535-1922, can be used to supplement this lesson, including additional annual reports from the board of Education of the Presbyterian Church, published in 1867 and 1868 and the “Catalogue of Lincoln University,” 1883-1884.

[5] These feminist theorists show an important aspect of the ambivalence of white philanthropists. As Gayatri Spivak has theorized, imperialist ideology, by definition, extends one group’s power and influence over another; this imbalance the benefactor’s advantage to keeping a beneficiary dependent on the majority group (73-74).

[6] These questions can easily be adapted into an online discussion board activity.

Works Cited

Catalogue of Lincoln University Chester County, Pennsylvania, for the academical year 1882-83. Oxford: 1882. America’s Historical Imprints: Afro-Americana Imprints, 1535-1922: From the Library Company of Philadelphia. Readex, Web. 17 May 2015.

Catalogue of Lincoln University Chester County, Pennsylvania, for the academical year 1883-84. Oxford: 1883. America’s Historical Imprints: Afro-Americana Imprints, 1535-1922: From the Library Company of Philadelphia. Readex, Web. 25 May 2015.

“Forty-eighth annual report of the Board of Education of the Presbyterian Church in the United States of America. Presented to the General Assembly, May, 1867.”Philadelphia: 1867. America’s Historical Imprints: Afro-Americana Imprints, 1535-1922: From the Library Company of Philadelphia. Readex, Web. 25 May 2015.

“Forty-ninth annual report of the Board of Education of the Presbyterian Church in the United States of America. Presented to the General Assembly, May, 1868.”Philadelphia: 1868. America’s Historical Imprints: Afro-Americana Imprints, 1535-1922: From the Library Company of Philadelphia. Readex, Web. 25 May 2015.

“Forty-seventh annual report of the Board of Education of the Presbyterian Church in the United States of America. Presented to the General Assembly, May, 1866.”Philadelphia: 1866. America’s Historical Imprints: Afro-Americana Imprints, 1535-1922: From the Library Company of Philadelphia. Readex, Web. 12 May 2015.

Grabb, Edward G., and S. L. Waugh. "Family Background, Socioeconomic Attainment, and the Ranking of Self-Actualization Values." Sociological Focus 20.3 (1987): 215-26. JSTOR. Web. 19 Apr. 2015.

“Liberia.” Encyclopaedia Britannica. Encyclopaedia Britannica Online Academic Edition. Encyclopedia Britannica Inc.: 2015. 25 May 2015.Web.

Reports of the Boards. Comp. Church Presbyterian. Vol. 4. New York: Presbyterian Board of Education, 1877. 487-586. Web.

Robinson, Lisa Clayton. "Lincoln University (Pennsylvania)." Africana: The Encyclopedia of the African and African American Experience, Second Edition. Ed. Kwame Anthony Appiah and Henry Louis Gates Jr. New York: Oxford UP, 2008. Oxford African American Studies Center. Mon May 25 10:31:00 EDT 2015.

Spivak, Gayatri Chakravorty. “Can the Subaltern Speak?” The Post-colonial Studies Reader. Ed. Ashcroft, Bill, Gareth Griffiths, and Helen Tiffin. London: Routledge, 1995. Print.

Wedin, Carolyn. "Lincoln University (Pennsylvania)." Encyclopedia of African American History, 1896 to the Present: From the Age of Segregation to the Twenty-first Century. Ed. Paul Finkelman. New York: Oxford UP, 2008. Oxford African American Studies Center. Fri May 15 17:07:53 EDT 2015.