Antebellum Christian Tracts and the “Africanist Presence”: A Lesson Plan for African American Literature Courses

Introduction: “Christians, attend, while I relate…” [1]

Legh Richmond’s The African Widow, a pamphlet circulated by the Christian-based American Tract Society in 1827, unwittingly displays a poignant example of the role Christianity has played in the creation and continuation of stereotypes of African Americans. The stereotypes invoked in the readable didactic poetry of The African Widow depict what Toni Morrison has named the “Africanist presence.”[2] While white supremacists and other proponents of slavery used Christianity to dehumanize and subjugate black people, antebellum abolitionists ironically also exploited Christian networks as venues for their own sociopolitical agendas.

The African Widow, a 25-page pamphlet included in the Readex collection Afro-Americana Imprints, 1535-1922, exposes an Africanist presence lurking in the published works of Christian-based organizations, including the American Tract Society (ATS). While instructing readers in Christian values, this tract synchronously appropriates enslaved black people’s stories of their experiences outside Africa. Richmond’s pamphlet allows various insights into how an exploitation of Christian networks and incorporation of an Africanist presence compounded the continuation of negative stereotypes of African Americans. Reading this pamphlet, students are able to evaluate three of its poems that center on the eponymous African woman character and her relationship with the tragedy of slavery. In addition, reading the pamphlet allows students to understand how early abolitionists taught white moral development and white superiority to children through Christianity.

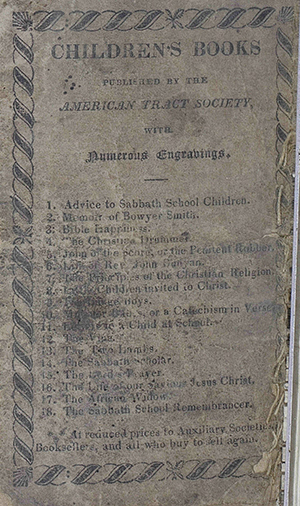

Richmond’s use of simple poetry to tell the African widow’s story illustrates how a racialized individual’s story was designed to benefit other people: in this case, the use of a black woman’s tragic story by the ATS for the moral development of young Christians. As a tract organization intent on disseminating Christian literature across the United States, the ATS (today merged with Good News Publishers) published numerous texts that appropriated the experiences of people of African descent as a medium for their Christian messages. While Richmond’s pamphlet exemplifies this appropriation, it is certainly not the only example, as illustrated by the advertisement for other ATS tracts intended for children. Present-day students can analyze the various tropes of poetry within this tract to decipher central themes such as personal tragedy and moral salvation. Concurrently reading Morrison’s Playing in the Dark, which addresses the usage of black bodies and non-normative narratives as part of the moral development of white characters, students will be better equipped to recognize and analyze the use of the Africanist presence in The African Widow.

Lesson Plan

The following lesson plan addresses the appropriation of the African body and a black person’s narrative as a way to propagate white Christian values, and it reveals the impact this appropriation had on white representations of African Americans. This material requires about two hours of class sessions to teach and is ideal for an (African) American Literature course.

Objectives

- To research as a class some of the texts published by the American Tract Society included in the Afro-Americana Imprints database

- To learn more about the ATS’s involvement in early 19th-century U.S. abolitionism

- To study the paratexts of The African Widow together with the ATS’s mission statement

- Notable paratexts include the title page, author’s introduction, and advertisement for other ATS publications

- Read The African Widow

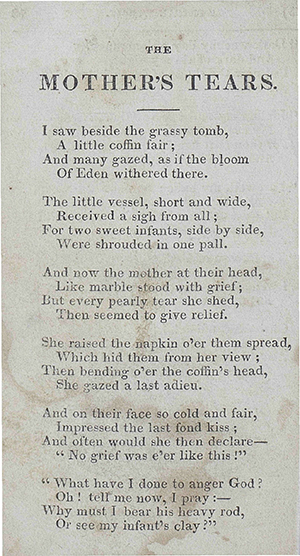

- Compare the development of the main character over the two subsections titled “The African Widow” and “The Mother’s Tears,” and read that treatment of the main character in the context of the last subsection, “The Power of the Gospel”

- Discuss the impact of Richmond’s use of Christian tenets on social perceptions of black-white moral development

- Read Playing in the Dark by Toni Morrison

- Summarize and analyze the concept of the Africanist presence

- Discuss Morrison’s theorization of white character development in relation to an appropriated African body or imagery of alleged “black” threat

Materials

- Afro-Americana Imprints access to The African Widow

- “The African Widow”

- “The Mother’s Tears”

- “The Power of the Gospel”

- Individual copies of Playing in the Dark by Toni Morrison

- Laptop computers or other digital devices to access AAI documents

- PowerPoint Presentation

- Include information on Christian abolitionist activism in America, particularly around 1827, the time of The African Widow’s publication

- Include details about Toni Morrison’s concept of the Africanist presence

- Include information on stereotypes of people of African descent and their origins and effects

Online Journal

An online journal will provide a space for students to record their individual thoughts and ideas about the material as the lesson progresses. The instructor can decide whether s/he wants to merge the online journal posts with the class discussion.

Before Reading The African Widow and Playing in the Dark

Students will begin maintaining their online journal by responding to key terms and images that have been distributed during a prior class. This activity is designed to reveal students’ preconceived concepts, and it will enrich discussion of the formation and perpetuation of stereotypes. Students should briefly record their initial reactions to each item. Later, students will write a longer paragraph (300 words) further analyzing the words and images.

Keywords or images could include:

- abolitionism

- Antebellum broadsides depicting black people’s bodies and/or Christian iconography

- The African Widow (images; as accessed in Afro-Americana Imprints)

- Africanist presence

- Stereotypes of black people

Bringing the Africanist Presence to the Forefront

Begin with a PowerPoint presentation featuring specific terms and images such as:

- Proslavery usages of Christianity

- Abolitionist activism in the 1820s and 1830s

- Publications of the American Tract Society

- Morrison’s Playing in the Dark

- “Africanist presence”

Group Activity

Read The African Widow and Playing in the Dark before class. Then, in class, form student groups of three or four. Ask each group to analyze a different section of the ATS tract, centering their attention on assigned questions. The students may also prepare and share any discussion questions that arose during their individual readings.

Discussion Questions:

- In light of a white author’s retelling of the eponymous African woman’s story, what effect is made by the narrator’s tone throughout the text, as in, for example, such passages as, “Ah no! her dark untutored mind / A stranger was to truth” (Richmond 5). What do your selected passages convey and how do they invite interpretation of the tract?

- What do the paratexts of The African Widow reveal about the American Tract Society’s missions?

- What sociopolitical forces seem to propagate the creation and maintenance of negative stereotypes of people of African descent?

- How are Christian mores used to uphold class and racial differences within The African Widow? (How) do economic and religious designs affect this black woman’s personal tragedy?

After Reading The African Widow and Playing in the Dark

Return to students’ individual online journals, once more responding to images and keywords but this time to record reconsiderations of the key concepts and unit readings. Morrison’s critical term “response-ability” (xi) can prove valuable as teachers lead students toward the conclusion of this project. The online journals give students an opportunity to reflect on shifts in attitudes on U.S. race relations, and also allow students to note how critical examinations of literature such as The African Widow and Playing in the Dark can disrupt misconceptions and unmask social and political forces upholding them.

Connections to Canonical American Literature

Toni Morrison’s Playing in the Dark will provide a critical lens necessary for the students to fully recognize and analyze the invocation of the Africanist presence inThe African Widow. Using this theoretical text, the students can be helped to see that the consequences of white authorship of black people’s stories did not cease with the circulation of The African Widow. Morrison’s theories will help delineate why critical examination of white authorship of black people’s stories is important and ongoing; her text offers a concise deconstruction and study of instances in canonical Anglo-American literature in which the Africanist presence is utilized. Morrison aptly illustrates that such instances are pervasive, and yet they go widely unnoticed as a form of appropriation because the stereotypes invoked are so deeply embedded within American culture. Her unveiling of the Africanist presence in specific works of literature, from texts published alongside antebellum ATS tracts to present-day literary works, allows the reader to recognize and confront those embedded stereotypes and creates a space for reflections on their origins. Ultimately, the students should discover that Morrison’s literary criticism can extend to an analysis of The African Widow as an early example of white invocation of the Africanist presence and appropriation of black bodies and narratives. Bringing moments of white literary imagination to the forefront and analyzing their place in an antebellum text promoting the end of slavery allows students to extricate both subtle and overt stereotypes and begin the process of creating valid spaces for African Americans within American literature. White authors should recognize their uses of actual or alleged African representations to connote something horrible or threatening or as a narrative strategy by which white characters are developed, especially when Christian organizations like the ATS assume they are helping both white children and black people but are actually indoctrinating white children from young ages with notions and constructions of white supremacy. By discussing what Morrison terms “response-ability” (xi), students should come to understand the sociopolitical dynamics that are constantly at play when writing and reading take place.

Conclusion: Freeing the Africanist Presence

By the conclusion of this lesson unit, students will have been exposed to the influence antebellum Christian organizations such as the American Tract Society had upon social and literary perceptions of enslaved black people’s stories and the role white appropriation of the Africanist presence played in creating stereotypes of people of African descent. After analyzing The African Widow, students gain a better understanding of how these stereotypes were (and remain) embedded in U.S. society. Furthermore, studying modern texts such as Toni Morrison’s Playing in the Dark, students are able to evaluate how those same perceptions and uses of the Africanist presence by white authors continues to affect the portrayal and the positionality of African Americans into the twenty-first century.

Footnotes

[1] From the first line of The African Widow.

[2] In Playing in the Dark, Morrison applies the term “Africanist presence” to denote the usage in American literature, primarily by white authors, of black characters or other signs of non-whiteness as a plot device or for white character development. Morrison calls for more studies of, “...the pervasive use of black images and people in expressive prose, the taken-for-granted assumptions that lie in their usage, and finally, the sources of these images and the effect they have on the literary imagination and its product” (x).

Works Cited

Morrison, Toni. Playing in the Dark: Whiteness and the Literary Imagination. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1992. Print.

Nord, David Paul. Faith in Reading: Religious Publishing and the Birth of Mass Media in America. New York: Oxford UP, 2004. Print.

Richmond, Legh. “ATS Advertisement.” The African Widow. Andover, Massachusetts: 1827. America’s Historical Imprints: Afro-Americana Imprints, 1535-1922: From the Library Company of Philadelphia. Readex, Web. 08 March 2015.

Richmond, Legh. “The African Widow.” The African Widow. Readex, Web. 08 March 2015.

Richmond, Legh.“The Mother’s Tears.” The African Widow. Readex, Web. 08 March 2015.

Richmond, Legh. “The Power of the Gospel.” The African Widow. Readex, Web. 08 March 2015.

"Welcome." Crossway. Web. 15 Apr. 2015. https://www.crossway.org/group/ats/