The Female Marine

In 1814, Boston printer Nathaniel Coverly Jr. published a pamphlet entitled An Affecting Narrative of Louisa Baker, which became an immediate bestseller in New England. It is an autobiography in which Miss Baker relates the story of her journey from idyllic rural Massachusetts to the depths of urban degradation in Boston to military glory on the deck of a Navy frigate during the War of 1812. She served as a seaman in the American Navy, dressed as a man for three years, never revealing her secret.

The notion of the “female warrior,” a woman fighting in the army or navy dressed in men’s attire was not new to popular literature. The ballad “Mary Ambree,” in which the heroine disguises herself as a man and goes to war to avenge her lover’s death, was first published as a broadside in London around 1600 and presumably had an oral tradition even older. “Mary Ambree” was the first of hundreds of ballads published before 1800 involving women dressing as men and distinguishing themselves in battle. The genre was as popular in America as it was in England, and some well-known female warrior songs such as “Jack Monroe” and “The Cruel War” were sung in rural Appalachia into the twentieth century.

Louisa Baker may have been familiar with these songs, but explicitly sites as her model the story of Deborah Sampson, a Massachusetts woman who actually did serve as a Continental Soldier in the American Revolution, disguised as a man named Robert Shurtleff. While in most ballads the woman is driven by a need to be by her lover’s side or to avenge her lover’s death, Deborah Sampson desired to fight for American independence and travel the country in ways which would have been impossible for a woman in the eighteenth century. Deborah Sampson was all business, as the cover of a 1797 biography, The Female Review: or Memoirs of an American Young Lady attests:

… she performed the duties of every department, into which she was called, with punctual exactness, fidelity and honor, and preserved her chastity inviolate, by the most artful concealment of her sex.

Louisa Baker’s reasons for putting on a man’s suit were much different than Deborah Sampson’s. Baker was not running towards a life of adventure; she was running away from a life of shame, and ultimately her story would raise a greater sensation than that of her idol. Baker was born in a small town forty miles outside of Boston. In her teens, she fell in love with, and was seduced by, a handsome young man who had promised to marry her. But after stealing her virtue, the young man left without fulfilling his promise. “I was conscious,” she says, “of having forfeited the only gem that could render me respectable in the eyes of the world.” She finds herself pregnant and, afraid to face her parents with her shame, she travels alone to Boston.

Looking for work as a servant, Louisa ends up in the household of a woman she believes is a kindly mother with a number of “darling daughters.” The mother nurses Louisa through her pregnancy, but the baby dies at birth. It is then that Louisa learns the true nature of the household. It is a house of prostitution, and her benefactor now demands that she work off the debt she has incurred or risk public humiliation.

Louisa Baker works for three years as a prostitute in the most degrading circumstances. She can see no escape, until one day, thinking of Deborah Sampson, she put on a sailor’s suit. Wearing a tight waistcoat underneath to conceal her breasts, she finds that she can easily travel through the city as a man with her gender unchallenged. Louisa then enlists in the American navy under the name George.

During the war of 1812, she fights in a number of engagements with British warships and distinguishes herself in battle. After three years’ service she takes her wages, buys new clothes, reassumes her female character and returns to Plymouth for a happy reunion with her parents.

The pamphlet sold so well that Coverly published a sequel in November 1815. In the second pamphlet, entitled The Adventures of Lucy Brewer, (alias) Louisa Baker, we learn that the protagonist’s real name is Lucy Brewer, her home is Plymouth, Massachusetts, and she sailed on the USS Constitution—“Old Ironsides.” She also relates some further adventures in which Lucy, in man’s attire, proves manlier than her foes.

Before settling down in Plymouth, Lucy Brewer, with her parents’ reluctant agreement, decides to take a trip to see more of the country. Because of the freedom it allows her, she puts on her uniform and once again becomes George. In Newport, Rhode Island, Lucy challenges a sailor to a duel, defending the honor of a young woman the sailor has insulted. The sailor backs down, proving that Lucy, still dressed as George, is the better man. The young woman is so impressed that she invites her benefactor to New York to visit her family. Lucy, in uniform, dines with the woman’s parents and brother, and they show her the sights. Then Lucy returns to her parents once more.

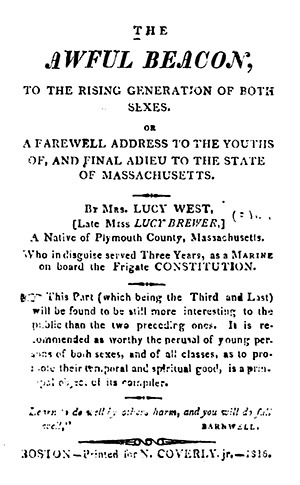

The sequel was also successful, and in May 1816, a third installment, The Awful Beacon of the Rising Generation, was published. In this pamphlet, the brother of a woman whose honor had been defended by Lucy recognizes the story printed in The Adventures of Lucy Brewer, and comes to Plymouth to meet again the defender of his sister’s honor—this time as a woman. The man, Charles West, begins courting Lucy, and finally marries her. The rest of the pamphlet is a caution to young women on the danger of prostitution and a warning to young men to avoid the threat of disease and theft by steering clear of prostitutes.

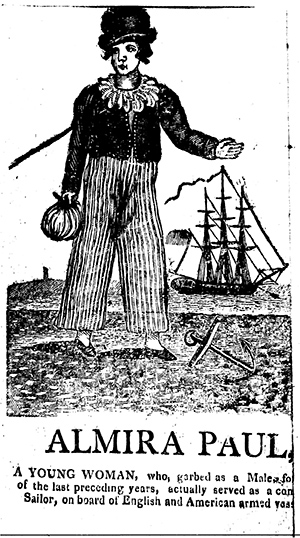

In 1816 the three pamphlets were combined under the title The Female Marine and between 1815 and 1818 there were at least nineteen editions of the Female Marine and its component parts. The success of The Female Marine prompted a number of imitators. Nathaniel Coverly Jr. himself published The Surprising Adventures of Almira Paul, A Young Woman who garbed as a Male, has for there of the last preceding years, actually served as a common Sailor, on board of English and American armed vessels, without a discovery of her sex being made. Mrs. Paul was the wife of a Nova Scotia sailor who was killed on board an English privateer fighting the Americans. To avenge his death, she dresses as man and joins the crew of an English ship in the War of 1812. In one engagement, Mrs. Paul identifies the American ship being attacked as the Constitution. If all of this is true, it means that Almira Paul and Lucy Brewer were fighting on opposite sides of the same battle.

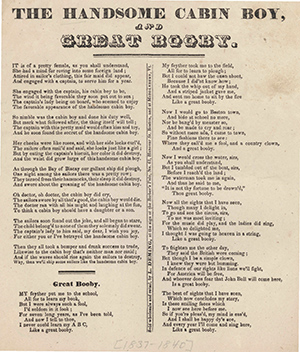

There were other tales of cross-dressing soldiers and sailors, as well as female pirates, both real and fictional, but eventually the craze died down. The ballads continued for some time, but had lost the sincerity of old songs. “The Handsome Cabin Boy,” published in 1837, seems to be a satire of the genre. In it a pretty young girl decides the best way to see foreign lands is to dress as a sailor and get a job as a cabin boy. The captain and his wife both take a shine to the handsome cabin boy, and the captain learns the secret because he “would often kiss and toy” with the cabin boy. It all comes to a head when the cabin boy becomes pregnant and,

The captain’s lady to him said, my dear, I wish you joy,

For either you or I’ve betrayed the handsome cabin boy.

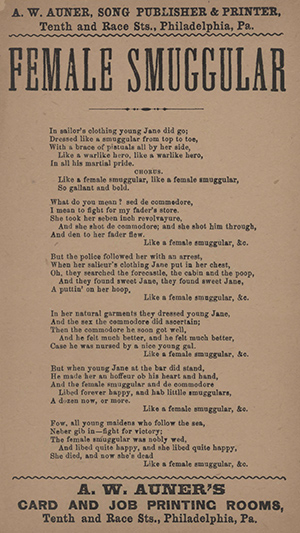

“The Female Smuggler,” published in 1871, tries to modernize the genre by infusing a bit of minstrel show dialect with phrases like,

And the female smuggler and de commodore

Libbed forever happy and hab little smugglars

A dozen now, or more.

As for Louisa Baker, aka Lucy Brewer West, historians have tried to verify her story, but unfortunately have not found any confirming records in Plymouth of Lucy Brewer, Louisa Baker, or Charles West, and no one on board the Constitution during the war of 1812 had a first or last name of George. The story was a very profitable work of fiction by Nathaniel Coverly Jr.

----------

Sources

Baker, Louisa. An affecting narrative of Louisa Baker, a native of Massachusetts: who, in early life having been shamefully seduced, deserted her parents, and enlisted in disguise, on board an American frigate as a marine .... New-York Printed by Luther Wales, Re-printed by Nathaniel Coverly, Jun., 1814

Brewer, Lucy. The adventures of Lucy Brewer, alias Louisa Baker. being a continuation of Miss Brewer's adventures ... comprising a journal of a tour to New York and a recent visit to Boston, garbed in her male habiliments : to which is added her serious address to th. Boston Printed by N. Coverly, Jr., 1815.

Brewer, Lucy. The awful beacon to the rising generation of both sexes, or, A farewell address to the youths of, and final adieu to, the state of Massachusetts. Boston: Printed for N. Coverly, Jr., 1816.

Cohen, Daniel A. The female marine and related works narratives of cross-dressing and urban vice in America's early republic. Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 1997. Print.

Dugaw, Dianne. Warrior women and popular balladry, 1650-1850. Cambridge [England: Cambridge University Press, 1989.

Female smuggular [sic]. Philadelphia: A.W. Auner, song publisher & printer, Tenth and Race Sts., Philadelphia, Pa., 1871.

Paul, Almira. The surprising adventures of Almira Paul a young woman, who, garbed as a male, has for three of the last preceeding years actually served as a common sailor on board of English and American armed vessels without a discovery of her sex being made .... Boston: Printed for N. Coverly, Jun., 1816.

Sampson, Deborah. The female review, or, Memoirs of an American young lady: whose life and character are peculiarly distinguished, being a Continental soldier, for nearly three years, in the late American war : during which time she performed the duties of every department. Dedham [Mass.: Printed by Nathaniel and Benjamin Heaton, for the author, 1797. Print.

The Handsome cabin boy, and Great booby. Boston: Sold wholesale and retail, by L. Deming, at the sign of the barber's pole, no. 61, Hanover St. Boston, and at Middlebury, Vt., 1837.

----------