“…According to the laws of God and the rules of the Indian department”: The Role of the Bureau of Indian Affairs and “Civilizing” Native Americans

This is the sixth in a series of blog articles highlighting primary source content from the Readex Native American Tribal Histories collection. The articles in this series offer further insight and added perspectives into westward expansion, the Trail of Tears, the history of Manifest Destiny, and the impacts to Native Americans.

In the 19th century, the U.S. Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) had a policy that aimed at assimilating Native American tribes into mainstream American culture. This policy was commonly known as the "Assimilation Policy" or the "Civilization Policy." The underlying premise was to push Native Americans to adopt colonialist European-American ways of life, including farming, Christianity, education, and private property ownership.

A significant part of the work of the BIA field agents was taken up with efforts to “civilize” or assimilate the Native Americans under their charge. To better understand those efforts, particularly in the Oregon and Washington Superintendencies, it is important to analyze and understand white Americans’ attitudes towards Native Americans and their cultures in the 19th century. In short, Native Americans were generally viewed by BIA agents as disorganized, lazy, childlike, violent, untrustworthy, and doomed. In their writings, BIA agents often mentioned their derogatory opinion of their charges.

In a letter to George Manypenny in June of 1853, Joel Palmer wrote,

A few of the Indians are inclined to industry, and are useful as laborers, but the mass are exceedingly indolent and improvident, and the propensity to gamble, as strong and universal in the red man, exists in all.[i]

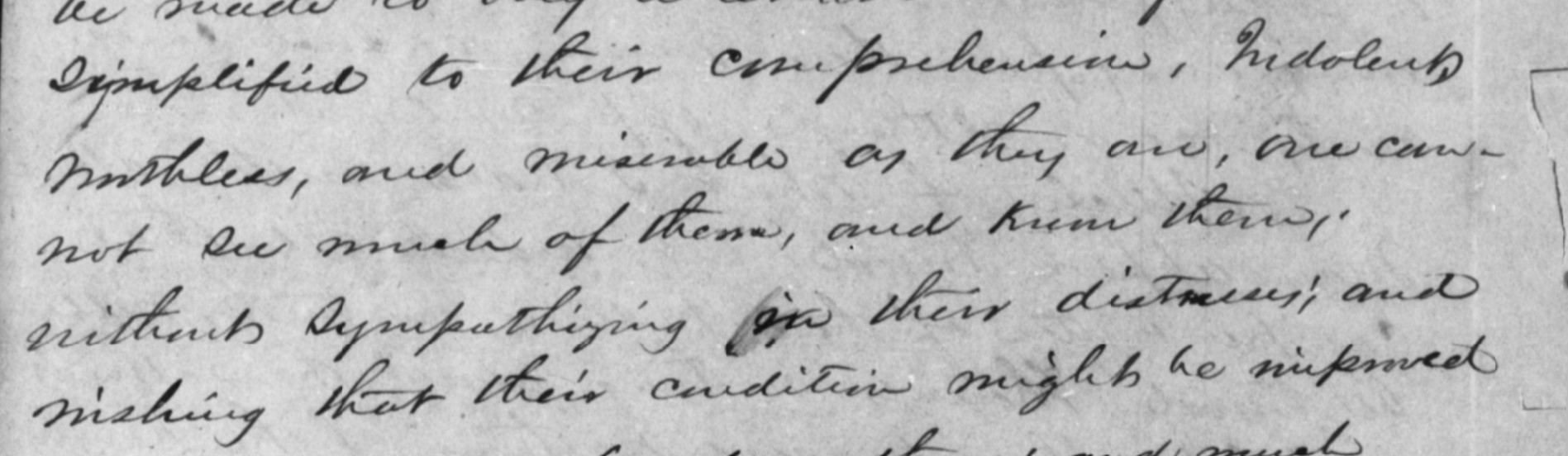

In December of the same year, Edmund A. Starling expressed similar sentiments in a letter to Isaac I. Stevens,

Indolent, worthless, and miserable as they are, one cannot see much of them and know them; without sympathizing in their distress; and wishing that their condition might be improved.[ii]

In an annual report to Isaac I. Stevens in 1854, William H. Tappan wrote of the Cascade Indians under his jurisdiction as though they were incapable of understanding:

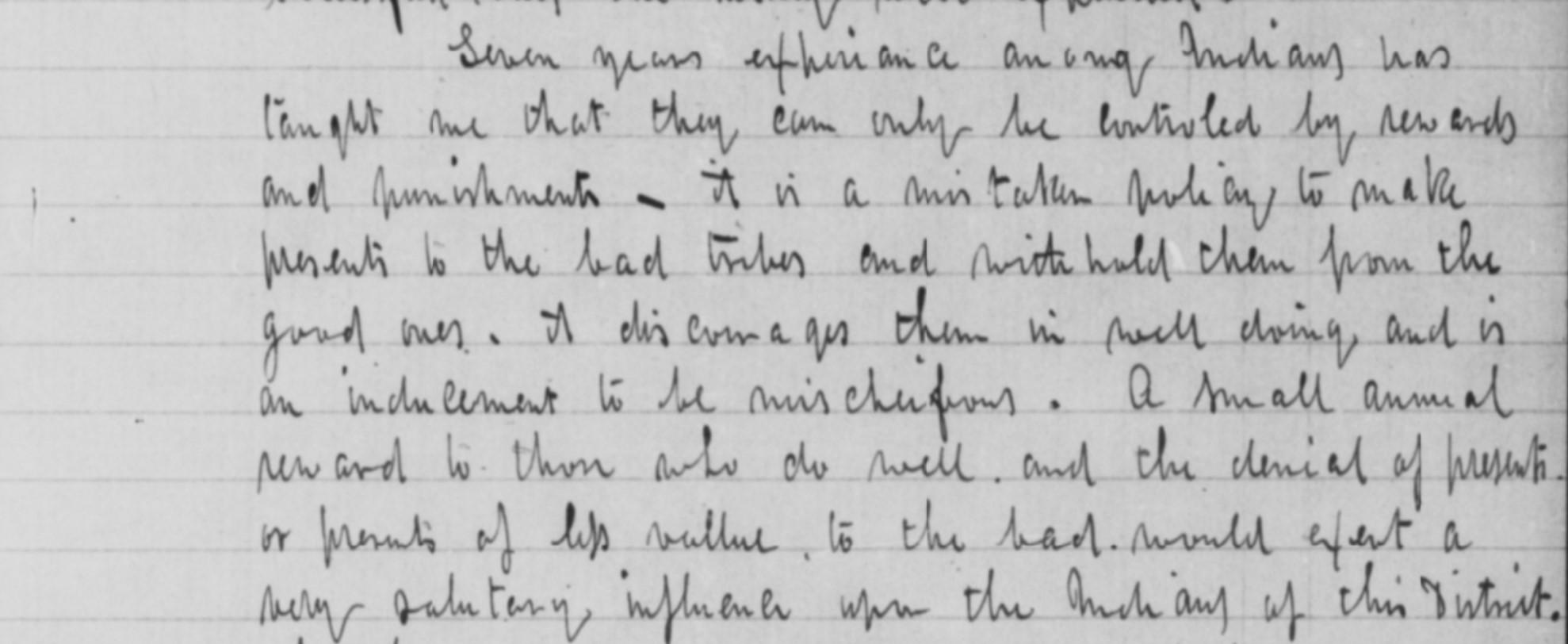

Seven years’ experience among Indians has taught me that they can only be controlled by rewards and punishments. It is a mistaken policy to make presents to the bad tribes and withhold them from the good ones. It discourages them in well doing and is an inducement to be mischievous. A small annual reward to those who do well, and the denial of presents or presents with less value to the bad would exert a very salutatory influence upon the Indians of this District…[iii]

Further, any efforts on the part of Native Americans to resist American colonialism or maintain their ancestral cultures was viewed as “bad” or “wicked.”

In a letter to Samuel Ross in 1870, Eugene C. Chirouse wrote,

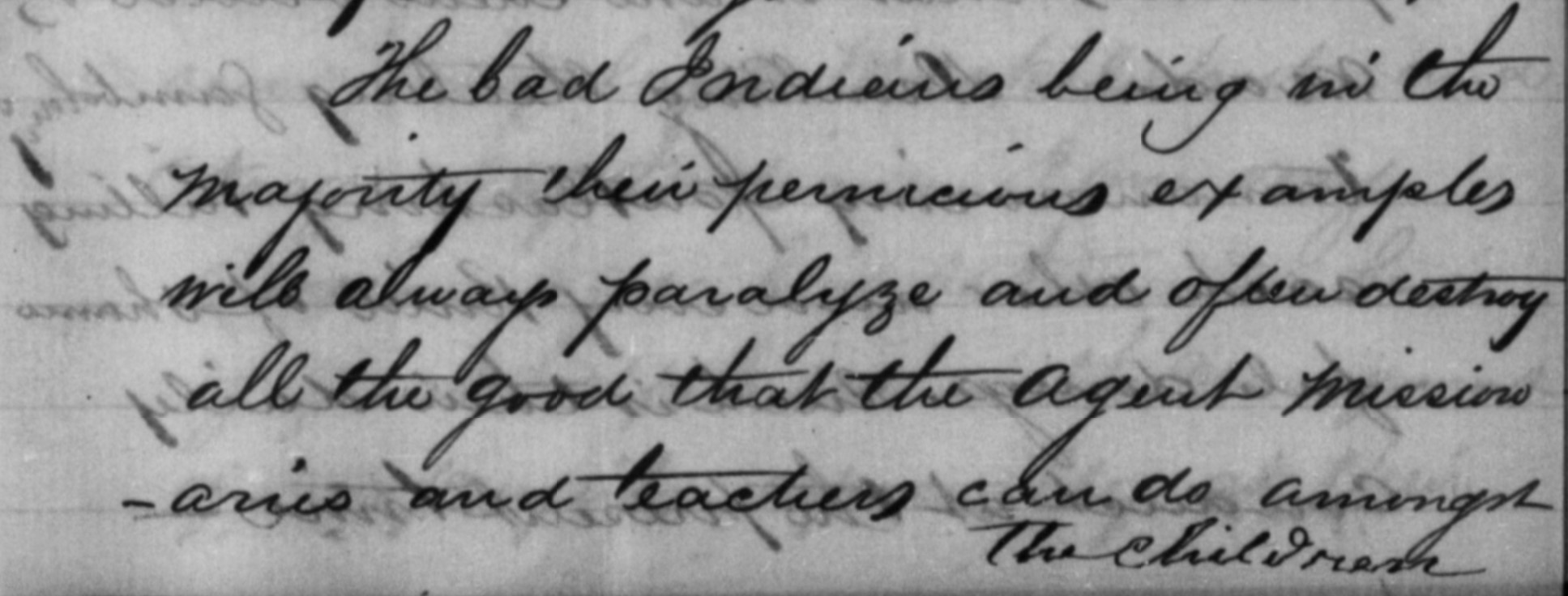

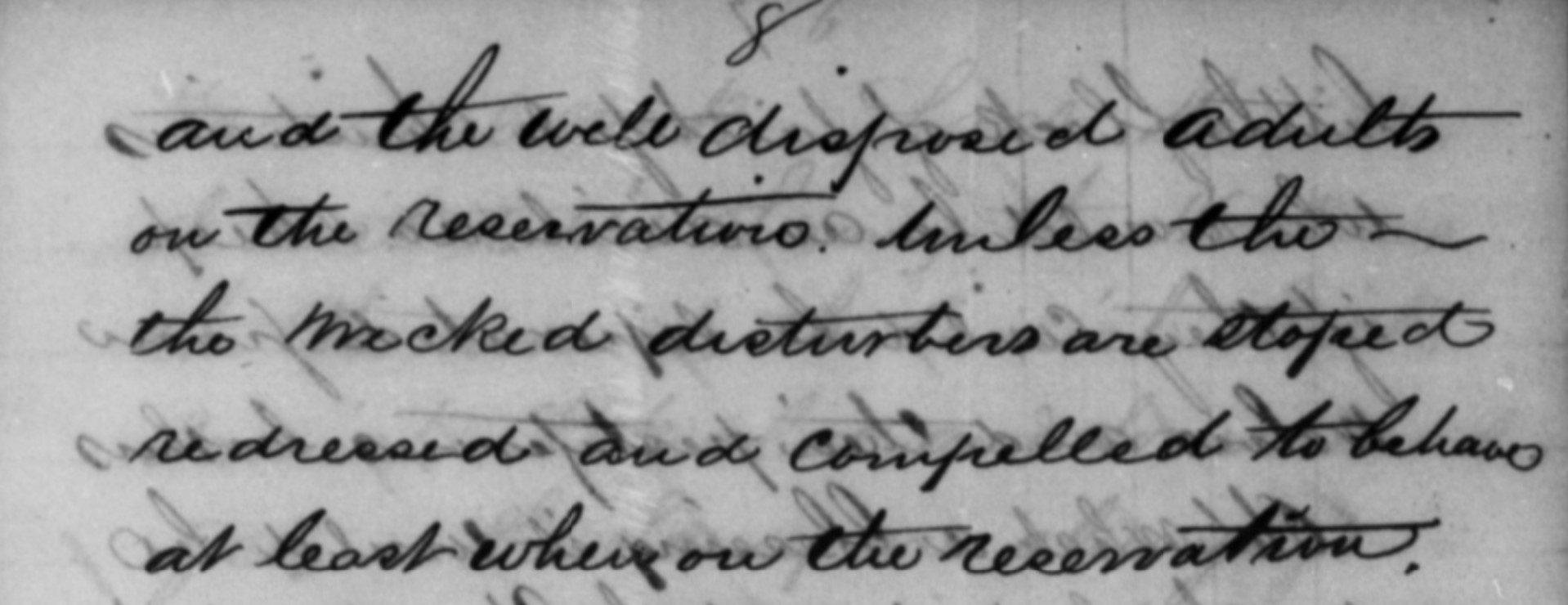

The bad Indians being in the majority their pernicious examples will always paralyze and often destroy all the good that the Agent Missionaries and teachers can do amongst the children and the well disposed adults on the reservations. Unless the wicked disturbers are stopped redressed and compelled to behave at least when on the reservation.

Additionally, Native Americans were not trusted with either money or significant responsibilities. In a letter from Charles E. Mix to Isaac I. Stevens in 1854, Mix advised,

I would also refer you to the late annual report of this Office, and the last annual report of the Secretary of the Interior, from which you will perceive that it is regarded by the Department as the best policy to avoid, as far as it can be judiciously done, the payment of Indian annuities in money, and to substitute implements of agriculture, stock, goods, and articles necessary to the comfort and civilization of the Tribe.”[iv]

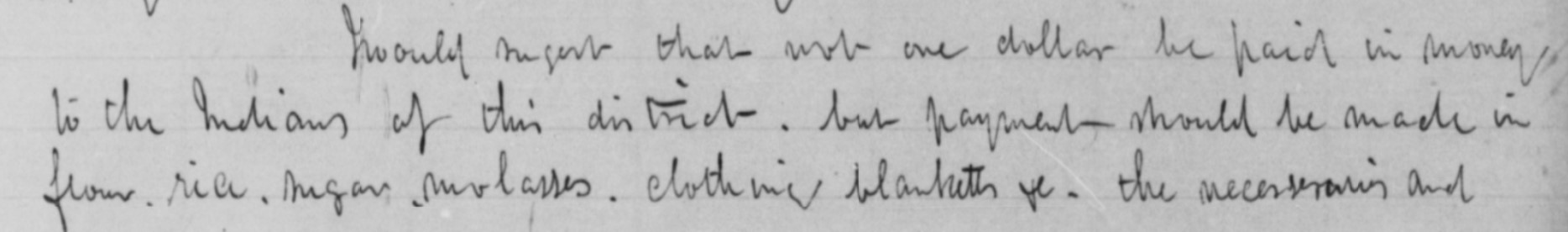

William H. Tappan wrote to Stevens later the same year to recommend,

…not one dollar be paid in money to Indians of this district, but payment should be made in flour, rice, sugar, molasses, clothing, blankets, &c. the necessaries and some of the comforts of life should take the place of coin, for that they cannot properly expend but will all be transferred to the pockets of the rum sellers, and I would further suggest that all blankets, clothing, and other articles… should bear the indelable [sic indelible] mark of the agency for which it was issued. This would make them less desirable as articles of merchandise, and would render the enforcement of the U.S. Law against this species of trade less difficult.[v]

While this policy was often framed by agents and officials as a measure to ensure Native Americans were not defrauded by the whites around them, it also curtailed the Native ability to participate in white economies and ensured their dependence on the BIA for basic necessities like food, clothing, and tools, all of which could be withheld to punish bad behavior.

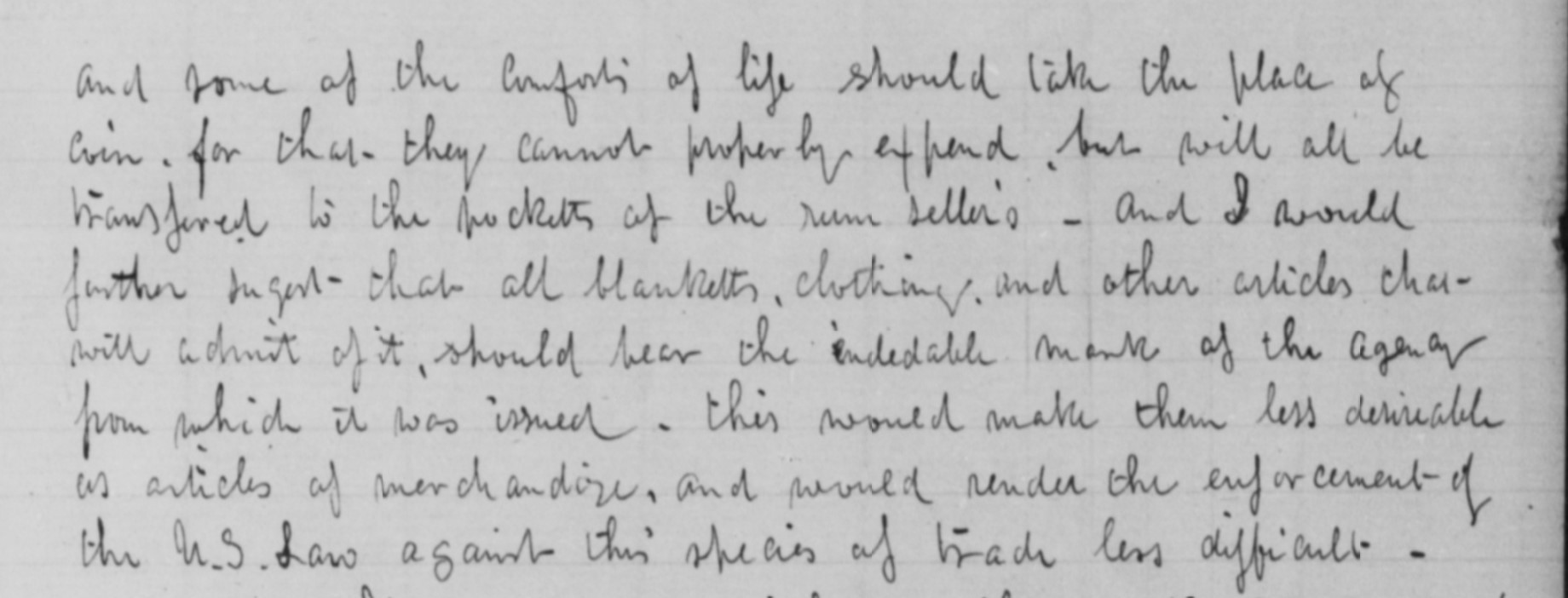

Lastly, Native Americans were frequently viewed as doomed or tragic. In a letter to George W. Manypenny in 1853, Joel Palmer said,

Vice and disease, the baleful gifts of civilization, are hurrying them away, and ere long the bones of the last of many a band, may whiten on the graves of his ancestors… Let completeness of plan, energy, patience, and perseverance characterize the effort, and if still it fail, the Government will have at least the satisfaction of knowing that an honest and determined endeavor was made to save and elevate a fallen race [emphasis added].[vi]

The Bureau of Indian Affairs Strategies to ‘Assimilate’ Native Americans

The Bureau’s strategy to assimilate or “civilize” Native Americans included two key steps. First, their goal was to corral Native Americans on reservations where they would pose no obstacle to white settlement and where agents could exert control over the adults. Next, to forcibly separate the children from their families, establishing Indian boarding schools. These schools aimed to eradicate Native languages and traditions, replacing them with English and Western cultural customs.

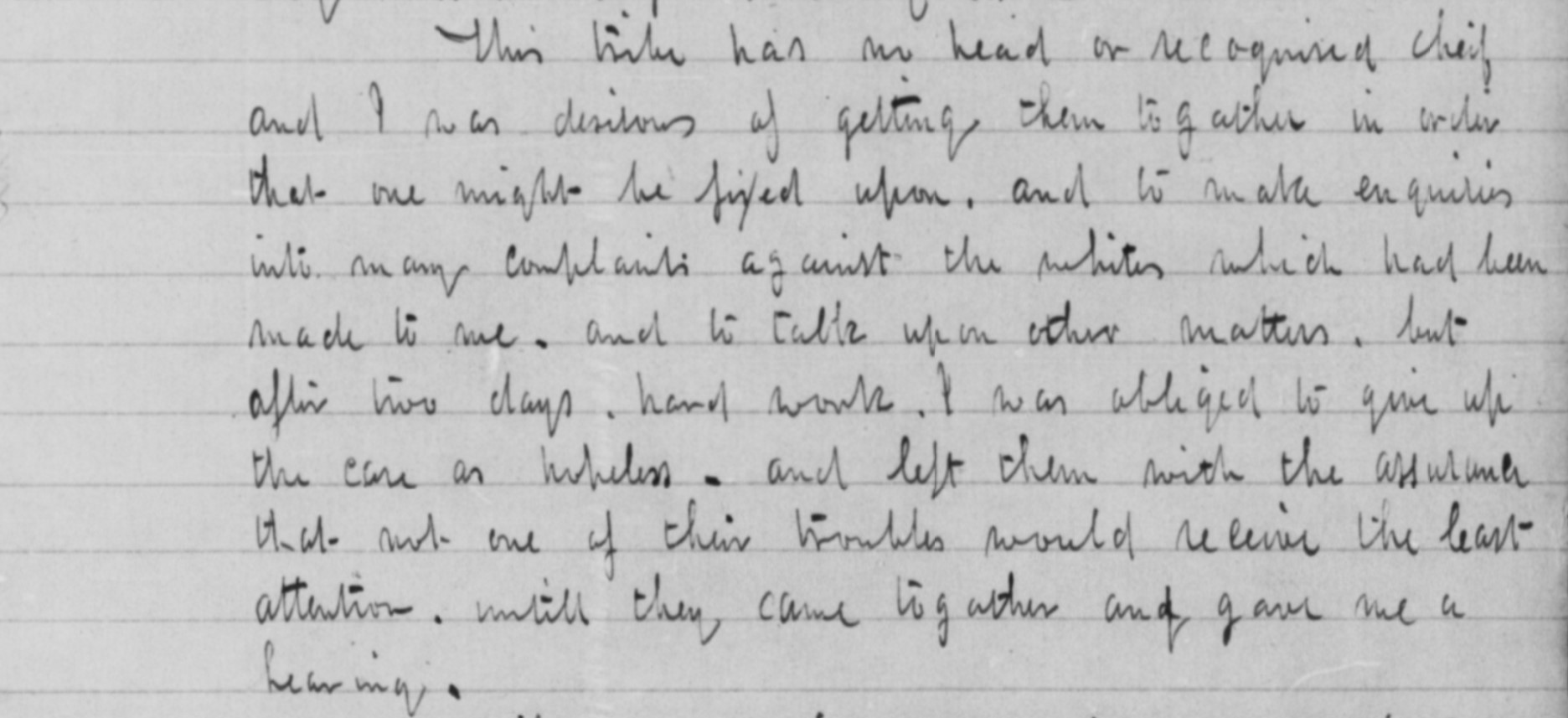

In the Washington and Oregon Superintendencies, BIA agents first needed to appoint chiefs, or consolidate the power structure among existing groups. In the eyes of the Bureau, chiefs were useful individuals who could act as intermediaries. If the hierarchy of the tribe did not include a chief, they imposed one.

Writing in 1853, Edmund A. Starling complained about the lack of chiefs with whom he could deal;

In scarcely none of the Tribes west of the Cascade mountains, do the Chiefs possess much authority over the rest. Any one, who has riches (in their sense of the word blankets & slaves) and is the head of a family considers himself a chief: and although there may be in name a chief or chiefs for the whole tribe, He or they possess but very little authority against the inclination of any of the rest beyond the circle of his relatives.[vii]

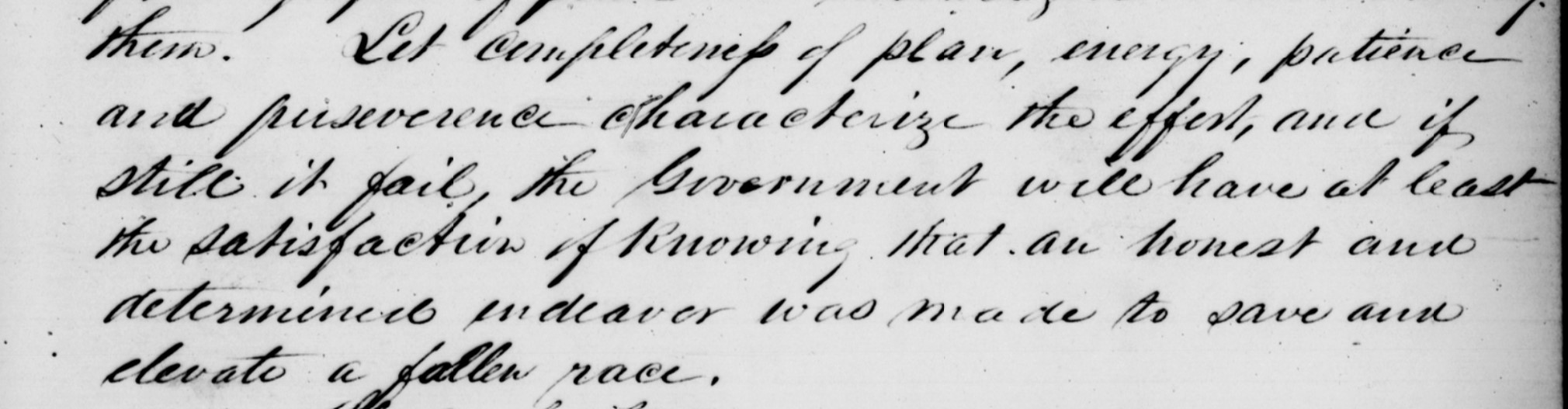

William H. Tappan complained in 1854 about his difficulty appointing a chief of the Chinook tribe;

This tribe has no head or recognized chief and I was desirous of getting them together in order that one might be fixed upon, and to make enquiries into many complaints against the whites which had been made to me, and to talk upon other matters, but after two days’ hard work, I was obliged to give up the case as hopeless, and left them with the assurance that not one of their troubles would receive the least attention until they came together and gave me a hearing.[viii]

It is worth noting Tappan visited the Chinook during salmon season, when they were at their busiest and simply did not have the time to spare talking to him.

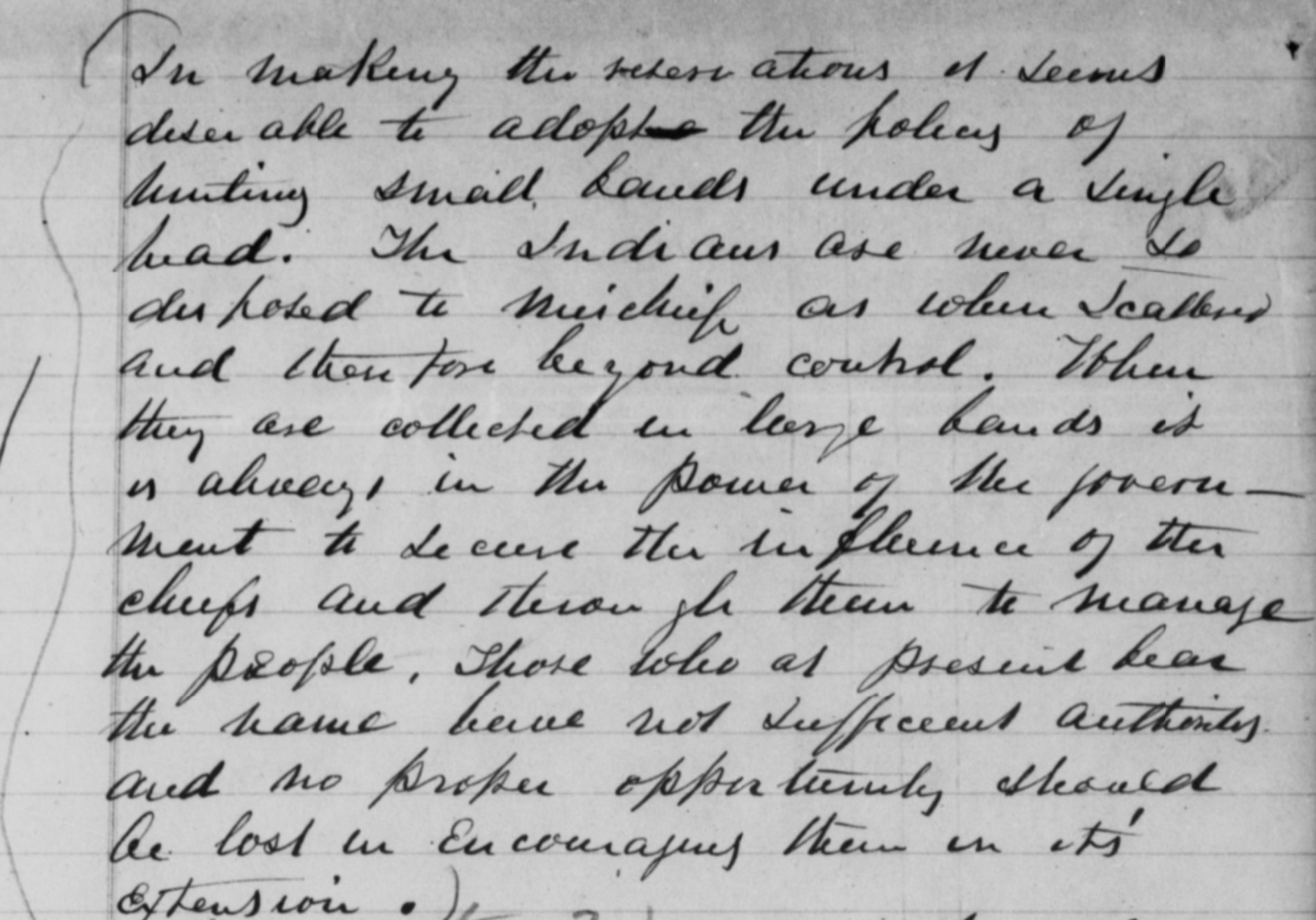

The Bureau suggested a policy change for the Washington Superintendency in 1855;

In making the reservations it seems desirable to adopt the policy of hunting small bands under a single head. The Indians are never so disposed to mischief as when scattered and therefore beyond control. When they are collected in large bands as above is it in the power of the government to secure the influence of the chiefs and through them to manage the people. Those who at present bear the name have not sufficient authority and no proper opportunity should be lost in encouraging them in its extension.[ix]

The Forced Eradication of Native American Cultures and the BIA Enforcement of "Civilized" Policies of Agriculture, Religion, and Residential Schools

Once they had installed tribal leaders who could be trusted to work with Indian Agents, the Bureau turned to enforcing a settled agricultural lifestyle when possible.

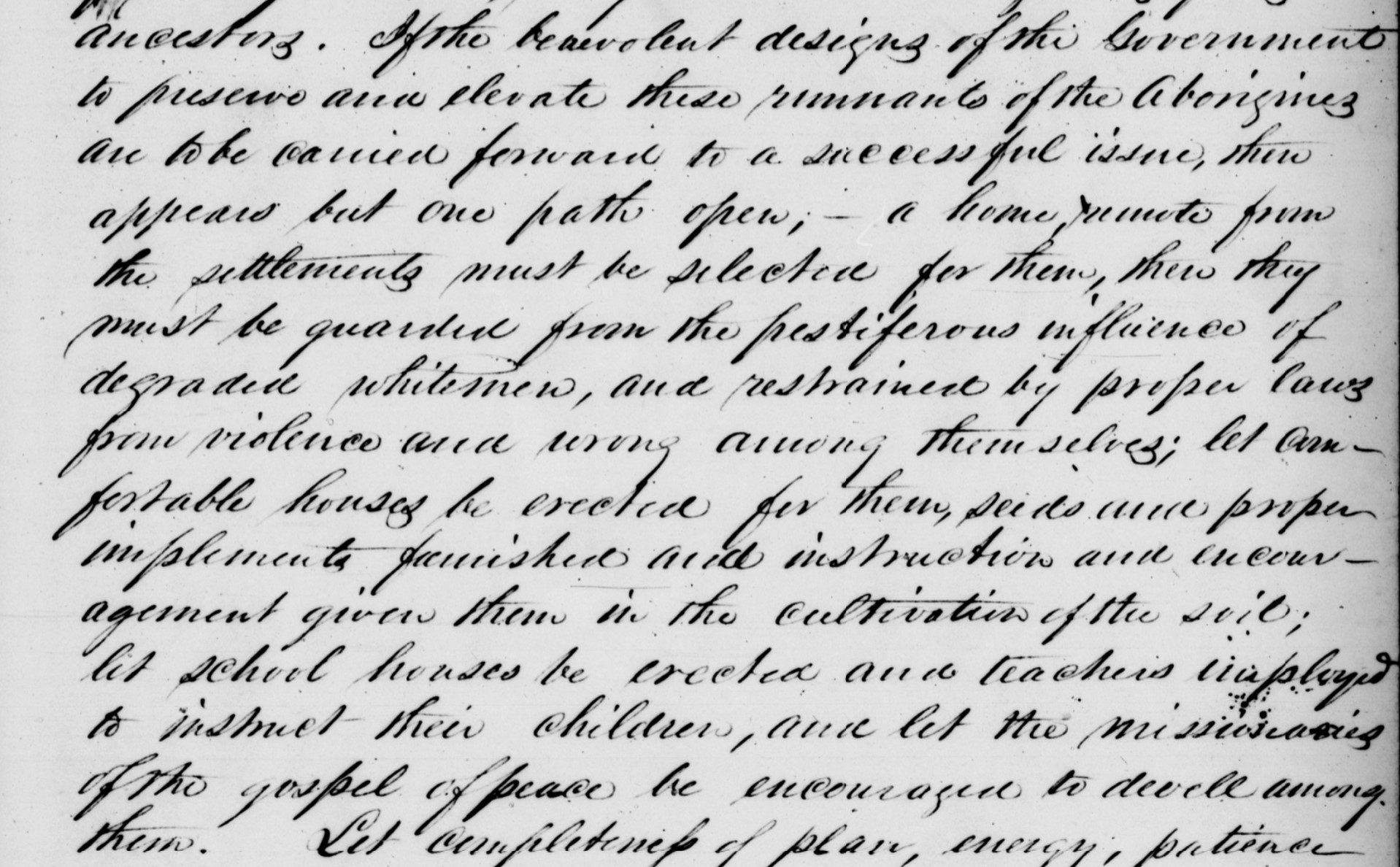

In a letter dated June of 1853, Joel Palmer wrote to George W. Manypenny,

If the benevolent designs of the Government to preserve and elevate these remnants of the Aborigines are to be carried forward to a successful issue, there appears but one path open – a home remote from the settlements must be selected for them, there they must be guarded from the pestiferous influence of degraded white men, and restrained by proper laws from violence and wrong among themselves; let comfortable houses be erected for them, seed and proper implements furnished and instruction and encouragement given them in the cultivation of the soil; let school houses be erected and teachers employed to instruct their children, and let the missionaries of the gospel of peace be encouraged to dwell among them.

Palmer’s suggestions followed the established policy of the Bureau; the project of “civilization” required every aspect of Native American cultures be abandoned or reformed to the whites’ sensibilities. Isolated on reservations away from white economies and often barred from pursuing their traditional foodways, Native Americans began to learn agriculture – to the delight of their agents.

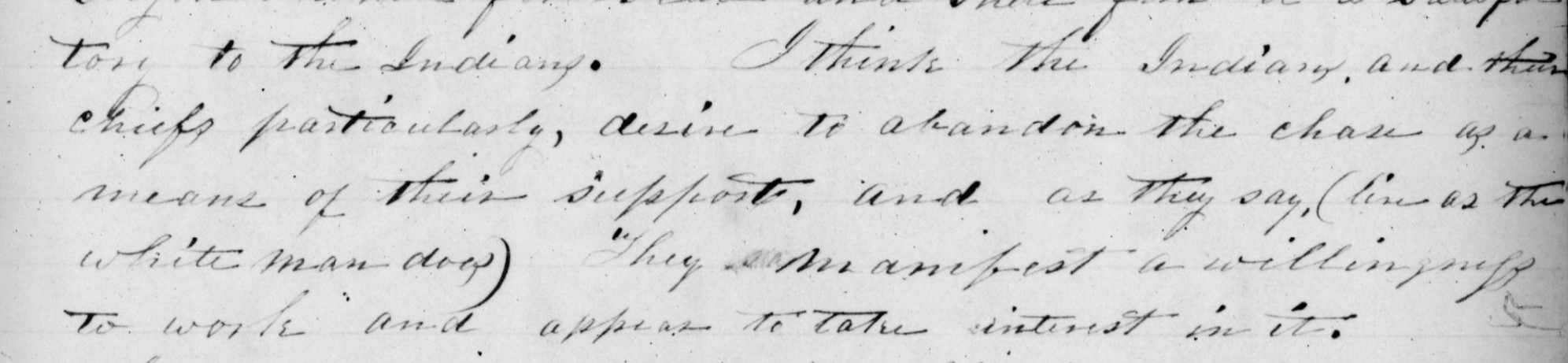

Linus Brooks wrote condescendingly in 1861,

I think the Indians, and their chiefs particularly, desire to abandon the chase as a means of their support, and as they say (like as the white man dogs) ‘They manifest a willingness to work’ and appear to take interest in it.[x]

Charles F. Winsor noted later the same year,

…they have cultivated an increased amount of land and seem to become from day to day, fuller and fuller convinced, that in husbandry will lay their future happiness; it is true, many, aye even the great majority of them, still continue their old habit of leaving their homes in the spring, in search of La Camas, Berries &c., but some have abandoned this custom, and live now permanently upon their land, which, to say the least, is certainly a beginning, and will, as these persons have more and better crops, for the season that they attend to them during the summer, than their roving neighbors, it is hoped, soon to be imitated by the entire tribes.[xi]

Indian Agents also believed that Native Americans – in their savage childishness – could not be allowed to drink alcohol, lest they become unruly, violent, or lazy.[xii]

Writing to Samuel Ross in 1870, Eugene C. Chirouse complained,

Whiskey sellers are the real destroyers of these poor Indians and notwithstanding they follow the advice of their murderous enemies cling to their wild habits, hate their Agent while he is making generous efforts to save them from ruin.[xiii]

Unruly behavior by Native Americans was often blamed on alcohol rather than on justified dissatisfaction with their situation or organized resistance to American colonialism. Local agents went to great lengths to curtail alcohol use on reservations.

In 1853, Joel Palmer wrote to George W. Manypenny,

Inconsequence of the increasing violations of the laws prohibiting the giving and selling of spiritous liquors to the Indians, and the great difficulty of convicting persons so engaged, I have deemed it advisable to appoint a special Agent to visit the different point where this traffic is most extensively carried on, and collect such information as would enable the Agents of the Department more effectually to breakup these establishments and bring the violators of the laws to justice.

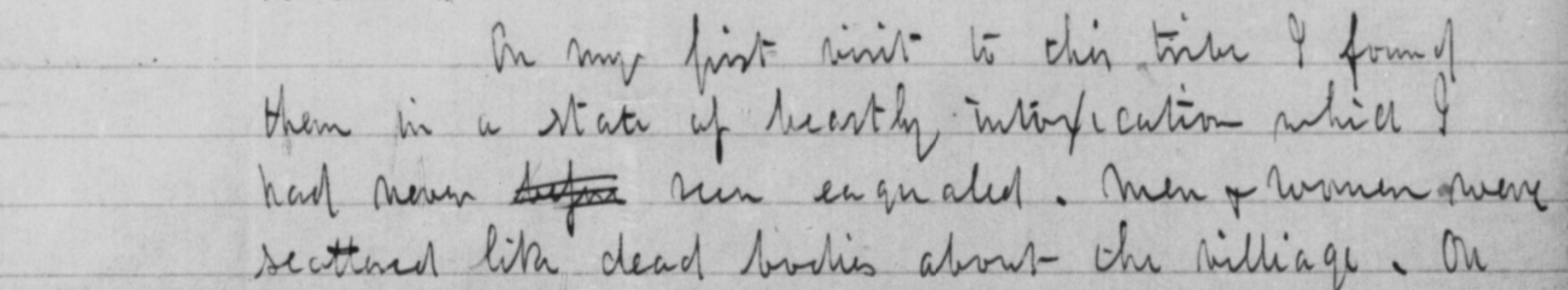

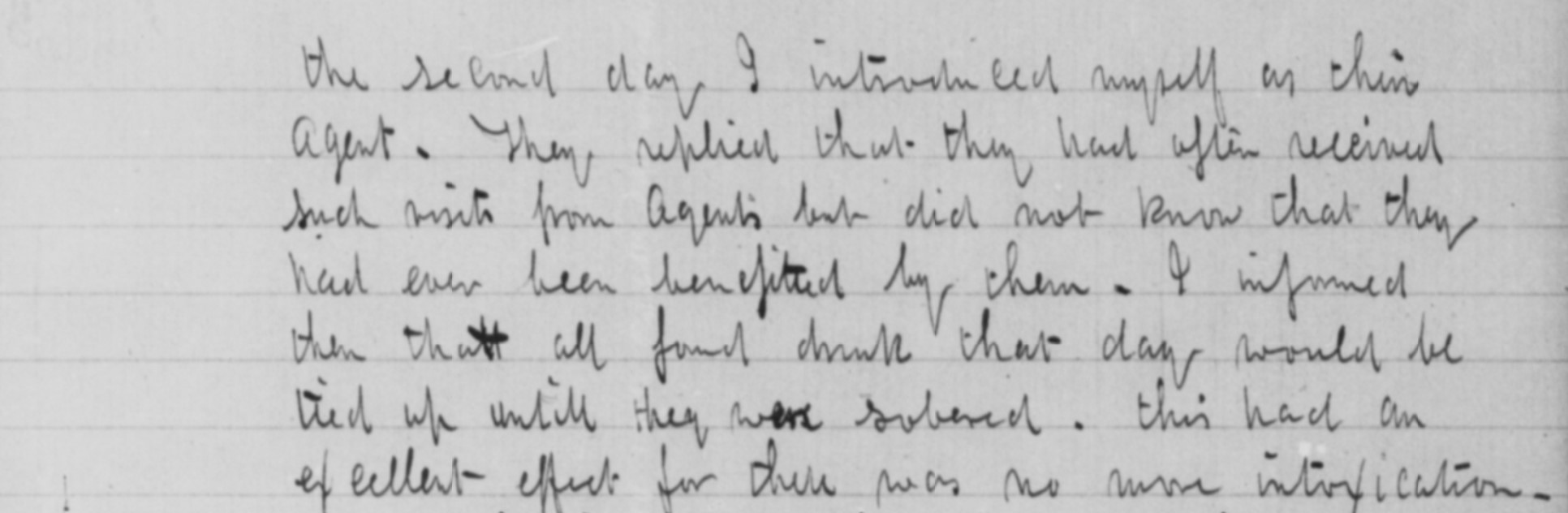

Another agent, William H. Tappan wrote about a visit to a Cascade village in 1854;

On my first visit to this tribe I found them in a state of beastly intoxication which I had never seen equaled. Men and women were scattered like dead bodies about the village. On the second day I introduced myself as their agent. They replied that they had often received such visits from Agents but did not know that they had ever been benefited by them. I informed them that all found drunk that day would be tied up until they were sobered [emphasis added]. This had an excellent effect for there was no more intoxication.[xiv]

Lastly, in their efforts to "civilize", the Bureau needed to convert Native Americans to Christianity. Missionaries were frequently encouraged to live near reservations and preach to the inhabitants, and many schools were staffed by religious organizations. Like every other aspect of the “civilization” project, Native resistance was viewed as a sign of wickedness.

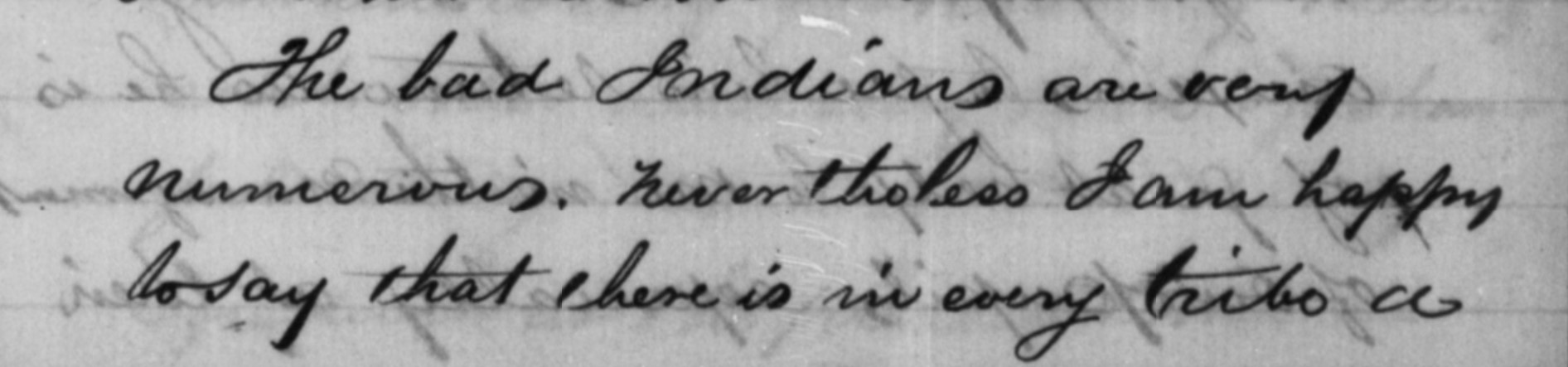

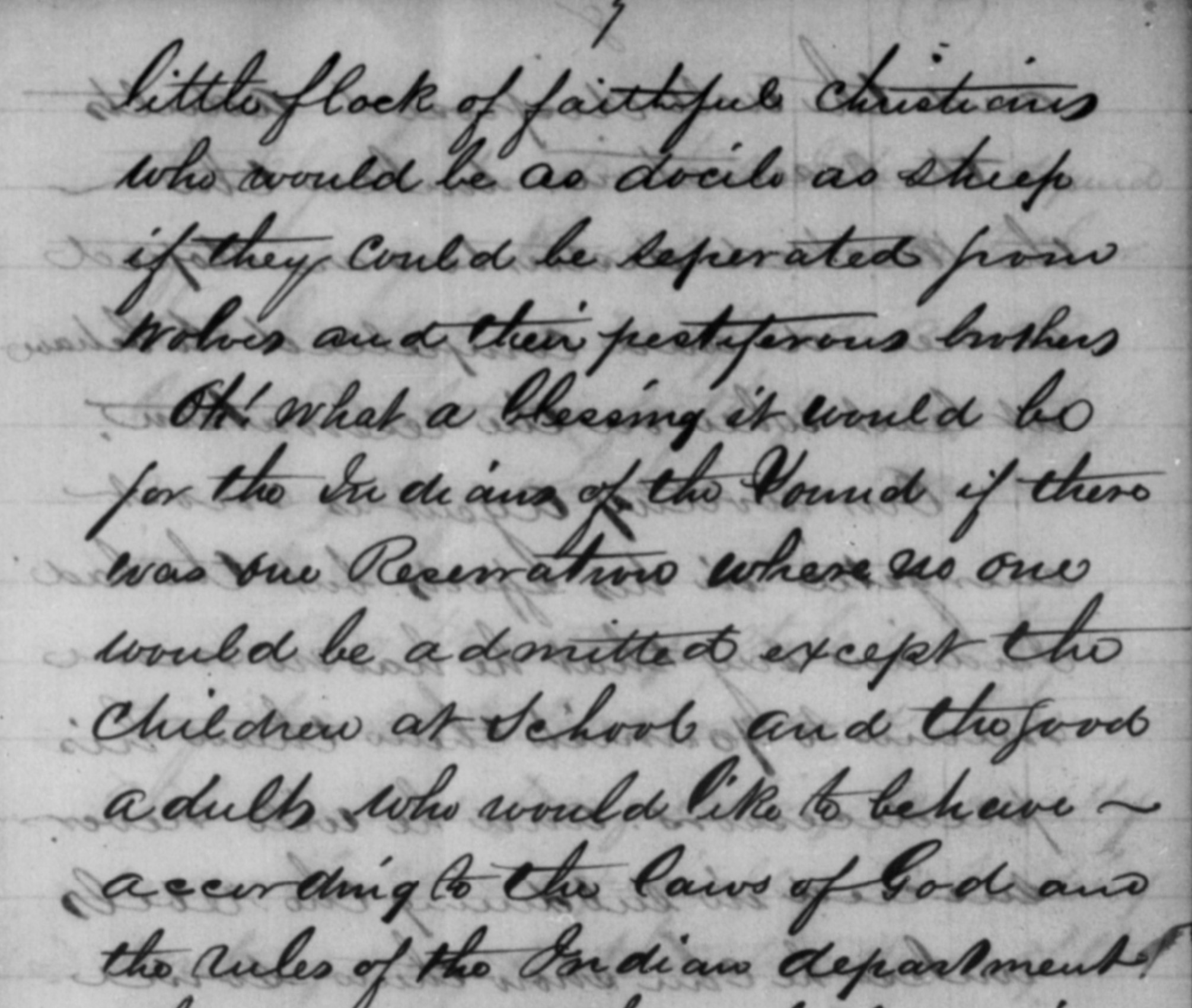

Eugene C. Chirouse wrote in 1870,

The bad Indians are very numerous. Nevertheless I am happy to say that there is in every tribe a little flock of faithful Christians who would be as docile as sheep if they could be separated from wolves and their pestiferous brothers. Oh! What a blessing it would be for the Indians of the Sound if there was one Reservation where no one would be admitted except the children at School and the good adults who would like to behave according to the laws of God and the rules of the Indian department.[xv]

In tandem with their efforts to control Native American adults, the Bureau of Indian Affairs also turned its attention to Native children, who it was believed would be more receptive to the whites’ “civilizing” efforts.

In a letter from Charles B. Hutchins to Edward R. Geary in 1861 about the reservation school, Hutchins wrote,

The school under the care of Rev. Mr. Wilbur Supt. of teaching, though having but few scholars reflects the highest credit upon him and his assistant Mr. Wright. Considering the difficulty of turning the Indian mind from its normal condition into the paths of Knowledge, and witnessing the skill and efficiency that some of his scholars already display, is abundant encouragement that of the aid of the Government be rightly directed, the most beneficent results will follow.”[xvi]

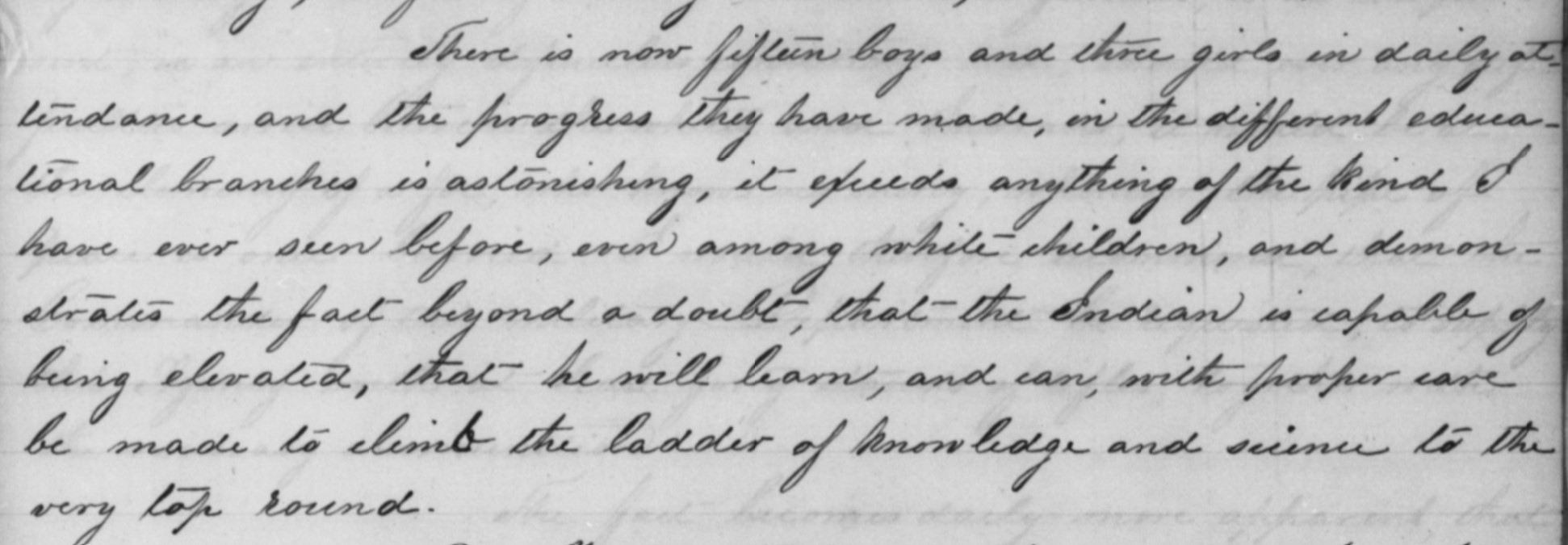

In another letter to Edward R. Geary in the same year, Wesley B. Gosnell said,

There is now fifteen boys and three girls in daily attendance, and the progress they have made, in the different educational branches is astonishing, it exceeds anything of the kind I have ever seen before, even among white children, and demonstrates the fact beyond a doubt, that the Indian is capable of being elevated, that he will learn, and can, with proper care be made to climb the ladder of knowledge and science to the very top round.[xvii]

While many reservation schools began as day schools, agents and Bureau officials soon advocated for boarding schools. This was often framed as a necessary measure to counteract the negative influences of the children’s homes, cultures, and families.

Charles F. Winsor wrote to Wesley B. Gosnell in August 1861,

Heretofore nothing but a dayschool has been kept among the Indians, and its success, to say the least, has been rather indifferent. It has always been my opinion, that the only way to succeed with Indian Children, is by taking them entirely away from their parents and not to allow the influences of their savage home to counteract those of the schoolroom [emphasis added].[xviii]

Another letter to William H. Rector quoted Edward R. Geary, who

…in his Report dated Portland, Oregon, October 1, 1860, [recommended] as ‘the only feasible plan for the accomplishment of valuable results.’ ‘Industrial Schools,’ he says, ‘where the most promising children may be placed, boarded and brought under proper discipline away from their homes and savage associates, presents, in my judgment, the only feasible place for the accomplishment of valuable results. The success, however, of this system, will depend on the wisdom, religious sentiment, and devotion to the enterprise of those to whom its operations are entrusted.’[xix]

It was not enough to simply remove the Native children from their homes and loved ones. Like their parents, Native children were subjected to “civilizing” efforts under the care of their teachers.

Writing in 1863, James G. Swan worried schoolteachers and officials were moving too quickly in their education efforts;

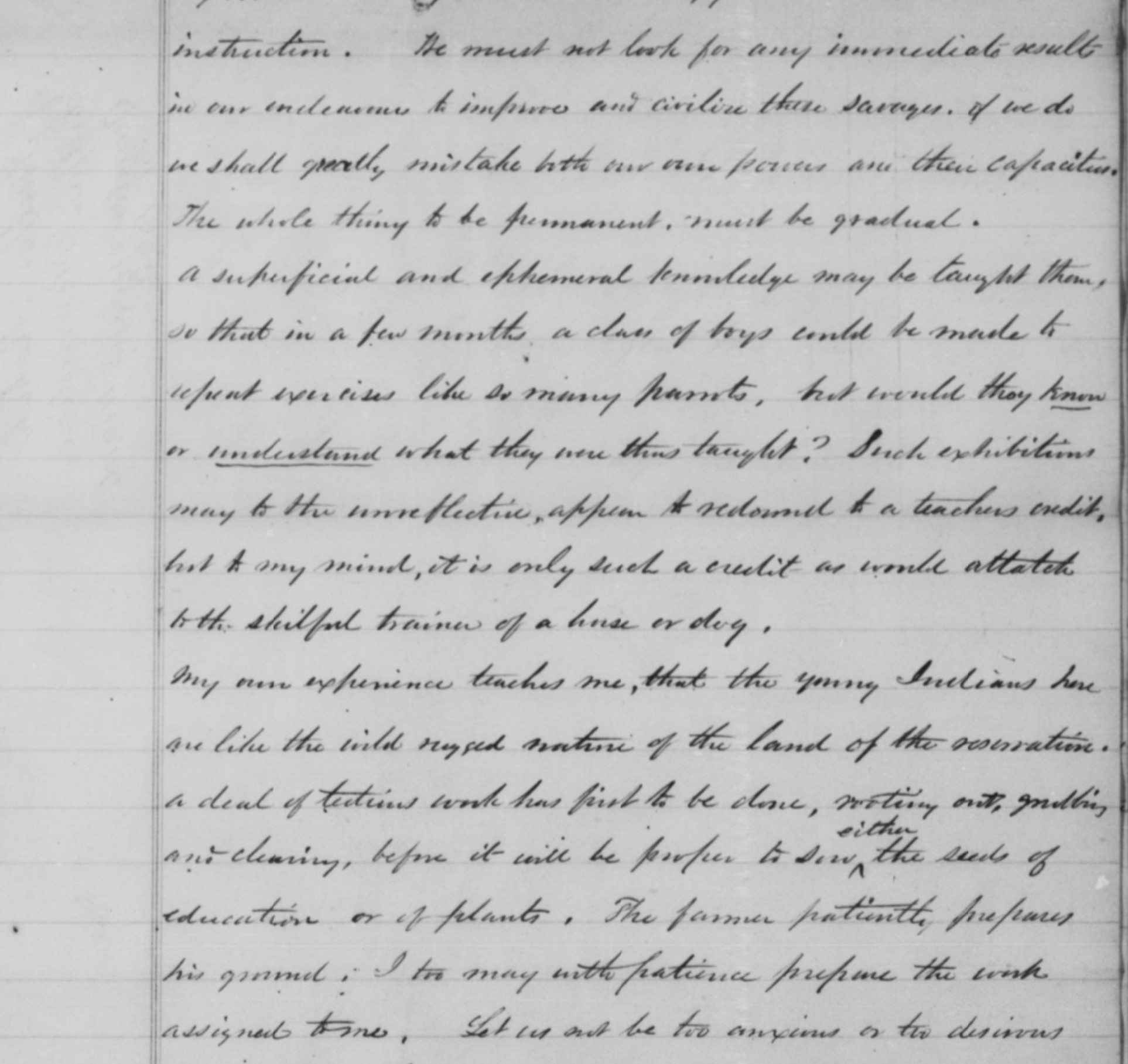

We must not look for any immediate results in our endeavor to improve and civilize these savages. If we do we shall greatly mistake both our own power and their capacities. The whole thing to be permanent, must be gradual. A superficial and ephemeral knowledge may be taught them, so that in a few months a class of boys could be made to repeat exercises like so many parrots [emphasis added], but would they know or understand what they are thus taught? Such exhibitions may to the unreflective, appear to rebound to a teacher’s credit, but to my mind, it is only such a credit as would attach to the skillful trainer of a horse or dog [emphasis added].”[xx]

Swan compared the children on his reservation to,

…the wild rugged nature of the land of the reservations. A deal of tedious work has first to be done, rooting out, grubbing, and clearing, before it will be proper to sow either the seeds of education or of plants. The farmer patiently prepares his ground; I too may with patience prepare the work assigned to me.[xxi]

Charles F. Winsor, writing to Wesley B. Gosnell in 1861, expressed a similar sentiment;

The lessons taught at the school should not confine themselves to letters, but the boys should be instructed in agriculture and the mechanical arts, and the girls in the use of the needle and loom. It is necessary first to civilize Indians, before they can be educated.[xxii]

What did “civilization” look like to Indian Agents and officials? By what bar did they measure success? The Bill for Indian Policy proposed to the Washington Superintendency laid out the parameters in 1855;

The great end to be looked for is the gradual civilization of the Indians and their ultimate incorporation with the people of the territories. The success of the Missions among the Pend d’Oreille & Coeur d’Alene Indians and the high civilization, not to say refinement of some of the Blackfeet women, who have been married to whites, shows how much may be hoped for.[xxiii]

However, “incorporation”, as imagined by the Bureau, was no less euphemistic than the “civilizing” means toward this end; the 1855 bill continues,

Another measure has been recommended which under proper regulations it is believed would prove of essential benefit to the Indians and of great convenience to the citizens. This is the establishment of a system of apprenticeship. Neither the Indians of the east or the interior have any objection to service… They are however inconstant in their labor. If a measure could be adopted which would give permanency to the relation of master and servant and at the same time protect the rights of the latter. The value of Indian labor would be greatly raised. The employment of Indians as farm servants would be especially useful to them, as at the expiration of their term of service they would carry back with them a sufficient knowledge of agriculture to improve their condition at home.[xxiv]

Even at its most successful, the project of “civilization” imagined Native Americans as subservient laborers.

[i] [Letter from Joel Palmer to George W. Manypenny, June 23, 1853]

[ii] [Letter from Edmund A. Starling to Isaac I. Stevens, Dec. 10, 1853]

[iii] [Annual Report from William H. Tappan to Isaac I. Stevens , Sept. 3, 1854]

[iv] [Letter from Charles E. Mix to Isaac I. Stevens, Aug. 30, 1854]

[v] [Letter from William H. Tappan to Isaac I. Stevens, Dec. 2, 1854]

[vi] [Letter from Joel Palmer to George W. Manypenny, June 23, 1853]

[vii] [Letter from Edmund A. Starling to Isaac I. Stevens, Dec. 10, 1853]

[viii] [Annual Report from William H. Tappan to Isaac I. Stevens , Sept. 3, 1854]

[ix] [Bill for Indian Policy, Dec. 22, 1855]

[x] [Letter from Linus Brooks to Edward R. Geary, July 23, 1861]

[xi] [Letter from Charles F. Winsor to Wesley B. Gosnell, Aug. 17, 1861]

[xii] While alcohol abuse is a significant problem for Native American communities today, this is more closely correlated with their marginalized status and other social factors than any physical predisposition.

[xiii] [Letter from Eugene C. Chirouse to Samuel Ross, Feb. 4, 1870]

[xiv] [Annual Report from William H. Tappan to Isaac I. Stevens , Sept. 3, 1854]

[xv] [Letter from Eugene C. Chirouse to Samuel Ross, Feb. 4, 1870]

[xvi] [Letter from Charles B. Hutchins to Edward R. Geary, June 30, 1861]

[xvii] [Letter from Wesley B. Gosnell to Edward R. Geary, Jan. 26, 1861]

[xviii] [Letter from Charles F. Winsor to Wesley B. Gosnell, Aug. 17, 1861]

[xix] [Letter from Rev. [illegible] to William H. Rector, May 8, 1862]

[xx] [Report from James G. Swan to Henry A. Webster, March 31, 1863]

[xxi] Ibid.

[xxii] [Letter from Charles F. Winsor to Wesley B. Gosnell, Aug. 17, 1861]

[xxiii] [Bill for Indian Policy, Dec. 22, 1855]

[xxiv] Ibid.

Other blogs in this series:

- Part 1: Native Removal Prior to the Indian Removal Act of 1830

- Part 2: Nineteenth Century Treaties with Native American Nations

- Part 3: “For the Great Father is angry, and will certainly hunt them down…”: Native American Wars Against United States Expansion

- Part 4: “We hope that henceforth we will be able to obtain our rights”: Native Political Pressure in the Nineteenth Century

- Part 5: “Like all other people, forbearance with them will cease to be a virtue…”: The Nez Perce Treaty of 1863

Visit the Readex Native American Tribal Histories page for information on this collection and to

request a complimentary trial.