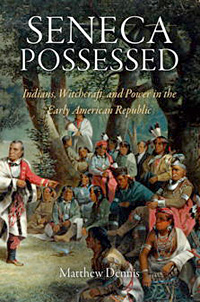

Murder! Or the Remarkable Trial of Tommy Jemmy, 19th-Century Seneca Witch-Hunter and Defender of Indian Sovereignty

I never read murder and mayhem stories in the newspaper. Such sensationalist accounts have been a mainstay of the U.S. popular press since it was invented in the early American republic, and they remain a prominent feature today. But the tawdry details of homicidal doings, breathlessly recounted, hold little appeal for me. And yet a few years ago one such story caught my eye and drew me in, sending me on my own investigative journey.

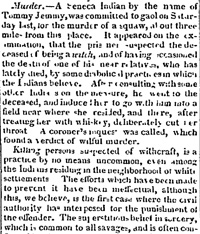

I read of the nefarious deed, not surprisingly, in the New York Post. Actually, the story appeared in the New-York Evening Post, not the well-known contemporary Gotham tabloid, and it recounted an event that had occurred nearly two hundred years ago, in western New York. (The Evening Post’s story was reprinted from Buffalo’s Niagara Journal of May 8, 1821.) The “crime” reported was murder, allegedly committed by a Seneca Indian man, Soonong-gize, commonly known as Tommy Jemmy. Death, even violent death, was not uncommon on the frontiers of the early republic, and Buffalo in 1821 was a frontier town. But the snippet account revealed this to be no ordinary homicide, nor was the case a simple whodunit. Tommy Jemmy never denied taking the life of the victim (a Seneca woman identified elsewhere as Kauquatau), but his defense would center on a surprising claim—that the act was not in fact “murder.”

The suspect’s surprising motive was clearly stated in the newspaper story: “It appeared on the examination, that the prisoner suspected the deceased of being a witch, and of having occasioned the death of one of his near relatives, who has lately died, by some diabolical practices in which the Indians believe.” In response, “after consulting with some other Indians on the measure,” Tommy Jemmy allegedly induced the suspected witch with some whiskey to accompany him to a nearby field, where he “deliberately cut her throat.” A coroner’s inquest “found a verdict of wilful [sic] murder,” arrested the suspect, and committed him to jail on Saturday, May 5, 1821.

If the “Law and Order” TV franchise ever seeks to extend its already attenuated reach to the early American past, it should consider ripping this case from the early 19th-century headlines. Whiskey, witchcraft, and a grisly murder, execution style: what more could a popular drama want? And to further fulfill the narrative formula, Tommy Jemmy was no ordinary “perp.” As the newspapers reported, “The prisoner is a Seneca chief, and is one of those who went to Europe in 1818. He possesses more than a common share of intelligence, but appears not to be conscious of having done any thing criminal or improper in the murder he has perpetrated.”

Such details intrigued me. Was he in fact a “chief” and uncommonly bright? Had he actually visited Europe? Did he feel no guilt or remorse? Subsequent research would reveal the answers to these questions while uncovering new and unexpected twists in the story of Tommy Jemmy, his trial, and the larger trials and tribulations of the Senecas in the half-century following the American Revolution, as they struggled (successfully) to survive as a people, preserve their sovereignty, and protect their lands in western New York.

Newspapers proved to be the critical source of information in reconstructing this history because court records, even when preserved, were laconic. In this era, New York courts did not provide detailed transcripts of testimony and proceedings, but newspapers did. We cannot believe everything we read in the newspaper, of course, but their reporting nonetheless provided vital firsthand accounts that take us closer to the action.

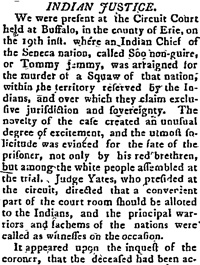

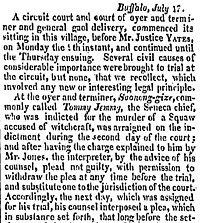

The Tommy Jemmy trial, which commenced in mid-July in a circuit court session at Buffalo, was widely reported. The August 3, 1821 edition of the Salem [Massachusetts] Gazette, for example, drawing from a Buffalo newspaper account, explained the Seneca defendant’s novel defense. Before an assembly of chiefs, the deceased—the alleged murder victim—had been formally accused of witchcraft and murder, both capital offenses, to which she confessed. Tommy Jemmy, a pine tree chief himself, then “acted as a minister of justice,” executing the convicted “witch” “in compliance with their custom from time immemorial, sanctified to them by the traditions of their ancestors, and in revenge of the deaths of various individuals of his tribe, who had perished by the sorceries of the defunct.”

In short, at issue was Seneca sovereignty and independence, guaranteed by various treaties and the U.S. Constitution. The defense argued the tribe’s right and duty to administer justice among its own people on its own land, which happened to be enveloped by the new state of New York. Tommy Jemmy, his defense concluded, had no more committed a crime in punishing the convicted perpetrator of a dangerous crime perpetrated within its jurisdiction than did the State of New York itself when it executed a homicidal felon.

Not surprisingly, this line of argument proved unsettling to many white New Yorkers, on a number of levels. But in response to “the ridicule which this doctrine excited” in the courtroom, the famous Seneca chief and orator Red Jacket arose and delivered a devastating speech. As the Gazette recounted, he “indignantly exclaimed,”

"What! do you denounce us as fools and bigots, because we still continue to believe, that which you, yourselves, sedulously inculcated two centuries ago? Your divines have thundered this doctrine from the pulpit—your judges have pronounced it from the bench—your courts of justice have sanctioned it with the formalities of law—and you would now punish our unfortunate brother for adherence to the superstitions of his fathers!—Go to Salem! Look at the records of your government, and you will find hundreds executed for the very crime which has called forth the sentence of condemnation upon this woman, and drawn down the arm of vengeance upon her. What have our brothers done more than the rulers of your people have done? And what crime has this man committed by executing, in a summary way, the laws of his country and the injunctions of his God?

Red Jacket’s speech cleverly deployed arguments designed to unnerve and disarm the white audience, embarrassed by its own superstitious acts during the Salem witch-hunting crisis of 1692 (which killed twenty, not hundreds), sensitive about its own image and reputation, and unsure about the complex interplay of rights and jurisdictions within the developing U.S. federal system.

What followed was perhaps even more surprising. As the Republican Chronicle reported from Buffalo on July 25, 1821 “the jury, after a few minutes absence, found a verdict that all the allegations contained in the prisoner’s plea were true.” Tommy Jemmy was not guilty? Thrown back on its heels, the prosecution sought successfully to arrest the judgment, and the case was referred to the New York Supreme Court. But this court too was forced to accept the merits of Tommy Jemmy’s and the Senecas’ arguments. The prisoner went free, and, it seemed, Seneca sovereignty claims were exonerated. But New York officials refused to accept the verdict and its implications, and, as the Watch-Tower reported from Albany, on April 8, 1822 the New York Assembly passed a “bill declaring the jurisdiction of the courts of this state, and for pardoning Soo-non-gize, otherwise known as Tommy Jemmy.” Bizarrely, the State of New York thus officially pardoned a man not actually convicted of any crime, to assert its own jurisdiction and sovereignty (unconstitutionally) over the Senecas and other Native people within state boundaries. Governor De Witt Clinton and the Council of Revisions quickly endorsed the measure on April 12.

Life went on for the Senecas, who would experience difficult times, endure the loss of considerable amounts of land, and suffer a diminution of their independence. But they survived and remained in their New York homeland, unlike, for example, most Cherokees, who were dispossessed by the State of Georgia, which cited the Tommy Jemmy bill of 1822 in its shameful proceedings. As in the Tommy Jemmy case, such details were widely reported in the newspapers, including at least one near the Senecas in upstate New York—the January 26, 1831 edition.

Tommy Jemmy lived on at Buffalo Creek (an important Seneca community and the site of the future city of Buffalo) where he served his community as an elder and chief. As late as 1835 his name appeared among the signatories of official letters to the Superintendent of Indian Affairs and President Andrew Jackson. The famous defendant had in fact been to Europe, as the newspapers reported in 1821. From late 1817 through early 1819, sponsored by Storrs and Company of Canandaigua, New York, Tommy Jemmy had led a troupe of Seneca performers who travelled to England and played to great acclaim in an Indian Show there—anticipating by 70 years the 1887 appearance of Buffalo Bill’s Wild West before Queen Victoria at Windsor Castle and other European venues. It’s likely that Tommy Jemmy died a peaceful death at home some time in the late 1830s. I wish some newspaper had printed an obituary.