The Life and Times of Frederick Douglass in Anacostia (Washington, D.C.) as told in the Washington Evening Star

From late 1877 until his death in early 1895, Frederick Douglass was the most prominent resident of Anacostia, the historic area located in Washington, D.C.’s Southeast quadrant. An internationally known writer, lecturer, newspaper editor, and social reformer, Douglass was a man of his neighborhood. He spoke regularly at nearby churches, invested in the area’s first street car line, and opened his Victorian mansion, Cedar Hill, to students from Howard University, where Douglass served on the Board of Trustees. Douglass’s many contributions to Washington, D.C. have been overlooked for too long.

With the digitization of the Washington Evening Star, researchers can now systemically track the growth of Anacostia, which became D.C.’s first subdivision in 1854, and the life and times of Frederick Douglass in the nation’s capital. Douglass moved from Rochester, New York, to Washington, D.C. in the early 1870s to publish and edit The New National Era, a weekly newspaper devoted to covering Reconstruction, the Republican Party, and black Washington.

A little over six months after the Evening Star’s debut in December 1852, a “Local Affairs” editorial appeared on June 22, 1853, invoking the name “Fred Douglass” for the first time.

Handiwork Abolitionists. – Any of our citizens who will take the trouble to walk through and around our city, can see what the skinflint abolitionists of the North are doing for us. There was a time when it was possible to preserve order among the negro portion of the population of Washington; but then the great majority of that portion were slaves. – Now, since Mrs. Stowe and her compatriots, Solomon Northup and Fred Douglass, have been exciting the free negroes of the North to “action,” and some of our resident “philanthropists” have been acting as agents in that “holy cause,” our city has been rapidly filling up with drunken, worthless, filthy, gambling, thieving free negroes from the North, or runaways from the South.

A little less than two decades later, the Union’s military victory over the Confederacy complete, during the Presidential administration of Ulysses S. Grant, Washington began to resemble a city worthy of its capital status. Under the leadership of the national and local Republican Party, city laws were liberalized, enfranchising black men and outlawing discrimination in public accommodations. An aggressive public works campaign created an infrastructure where none had been.

In early 1871 Washington was given its own limited form of territorial self-government with a bicameral legislature of a popularly elected lower house and an appointed upper house. Finishing second to Union General Norton Parker Chipman for the Republican nomination for Delegate to the United States House of Representatives, Douglass was appointed in April of that year to the city’s eleven-member Legislative Council by President Grant. With the demands of running his newspaper and other commitments Douglass’s career as a city legislator, however, was short-lived. On June 20, 1871, Douglass resigned. His eldest son Lewis would fill his seat.

Douglass would later serve a short stint as President of the insolvent Freedman’s Savings Bank, be confirmed by the Senate as the city’s United States Marshal during the administration of Rutherford B. Hayes, and work as Recorder of Deeds for more than five years across the presidencies of James Garfield, Chester Arthur, and Grover Cleveland. Actively campaigning in 1888 for Republican Benjamin Harrison, Douglass was rewarded with an appointment as Minister to Haiti.

Douglass’s private affairs were often reported by the Star and other city newspapers. After grieving over the death of his first wife, Anna Murray, in August 1882, Douglass upturned Washington society in January 1884 by marrying Helen Pitts, a white woman from a New York abolitionist family. While other papers used the event to foster intrigue and controversy, the Star simply continued to report on Douglass, matter-of-factly, as an important civil servant and leading man of Washington society.

While the residents of Anacostia and surrounding villages played a waiting game with the D.C. Board of Commissioners and city water department to lay a line “carrying the water across the Eastern Branch,” Douglass’s Cedar Hill had its own source. “A large spring at the foot of the hill in the rear of the house, yields a plentiful supply of pure water, and a pump in the rear of the stable supplies the stock,” observed the Star in 1889. It was also noted that “Mr. Douglass’ horses are unexceptionally fine, and are kept in the best manner.”

After returning to Washington from Haiti in early December 1891, Douglass entertained a small group of friends at Cedar Hill. They were joined by a Star correspondent, who described the event in the paper’s Anacostia neighborhood column: “The parlors of Mr. Frederick Douglass were comfortably filled Wednesday evening with musical and literary people.” After a poem was read, “Joseph H. Douglass, grandson of Frederick Douglass, rendered several violin solos with finish and effect,” moving the guests to dance. Next, “Mr. Douglass, elder, played ‘Home Sweet Home,’ on his violin and refreshments were served.”

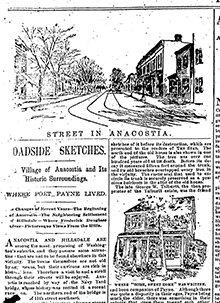

On the next day, December 5, 1891, the Star devoted two entire columns, enhanced with four etchings, to bring to life the “Village of Anacostia and Its Historic Surroundings.” The subhead noted, “Where Frederick Douglass Lives.” And the article devoted a full paragraph to the neighborhood’s most noteworthy resident.

Anacostia can at least boast of one historic character among her citizens—a man whose name and fame are probably world-wide. Frederick Douglass, the foremost man of his race in the country, lives in the old Van Hook house, built by one of the founders of the town, on Cedar Heights, between Pierce and Jefferson streets. The house, which is quite attractive, stands on a beautiful knoll, from which one of the finest views of the city of Washington found within the District is presented.

Less than a month before his sudden death in 1895, Douglass was part of a small gathering of the Citizens’ District Suffrage Petition Association at Green’s Hall on Pennsylvania Avenue. After the executive committee read its report and official business closed, Douglass spoke first.

“Neither the frowns nor the smiles of the present government could deter him from expressing his partisanship in the cause of liberty,” wrote a correspondent for the Star. Douglass reportedly asked, “[W]hat have the people of the District done that they should be excluded from the privileges of the ballot box? Where, when and how did they incur the penalty of taxation without representation?” (The rallying cry of “taxation without representation” remains in currency among today’s advocates for full voting rights for District residents.)

On the evening of February 20, 1895, Douglas collapsed in the hallway of his Anacostia home. By the time the doctor arrived, Douglass had passed. Word quickly spread, first throughout Washington and then the entire country. Tens of millions of Americans learned the news in their paper the next day. The Evening Star editorialized:

Of remarkable men this country has produced at least its quota and among those whose title to eminence may not be disputed the figure of Frederick Douglass is properly conspicuous—a fact that will be accentuated by the sudden death of him who did so much for himself and for the enslaved millions of his race who by force were compelled to residence in this country....

It is not enough to say that Frederick Douglass was a great man—the term has degenerated and is frequently misapplied, it is, but fair to show wherein his greatness was and what it consisted. Self-elevated from the degrading depths of slavery and ignorance to the highest plane upon which philanthropic man may here stand, he retained to the last simplicity such as is but rarely to be found in those who have come up through great tribulations and accorded place in the midst of the mighty....

To the masses for whom he toiled so incessantly and risked so much, the memory of Frederick Douglass should be especially precious, yet he cannot be regarded as wholly theirs; he was an American, of whom the whole people can truthfully say nothing but good and of whose friendship no human being—no matter what his racial origin—could be otherwise than proud.

On Monday, February 25, the city’s colored schools closed. Out of respect for the dead, businesses run by black Washingtonians closed as well. At dawn, an assembly of men, women, and children had already gathered outside the Metropolitan African Methodist Episcopal Church, waiting to pay their respects and view the body of Frederick Douglass.

As the sunny morning hours passed the gathering swelled until, when the blue-coated policemen came to take charge, the crowd reached down M street to 15th and down that thoroughfare past L street.

At eight thirty in the morning, after a private service was held at Cedar Hill for Douglass’s immediate family, a “colored camp of the Sons of Veterans” took guard of the casket as it made its way downtown. Along the way, hundreds of people joined the procession. “A few minutes before 10 o’clock a plain hearse drove slowly through the waiting concourse to the church doors, where it was met by the trustees of the church,” reported the Star.

Read at the funeral by Susan B. Anthony, and printed in the Star as part of its funeral coverage, was a public letter from suffragist Elizabeth Cady Stanton, who wrote:

Taking up the morning Tribune, the first words that caught my eye thrilled my very soul. "Frederick Douglass is dead!" What vivid memories thick and fast flashed through my mind and held me spellbound in contemplation of the long years since first we met.

Trained in the severe school of slavery, I saw him first before a Boston audience, fresh from the land of bondage. He stood there like an African prince, conscious of his dignity and power, grand in his physical proportions, majestic in his wrath, as with keen wit, satire and indignation he portrayed the bitterness of slavery, the humiliation of subjection to those who in all human virtues and capacities were inferior to himself. His denunciation of our national crime, of the wild and guilty fantasy that men could hold property in man, poured like a torrent that fairly made his hearers tremble....

As an orator, writer and editor, Douglass holds an honored place among the gifted men of his day. As a man of business and a public officer he has been preeminently successful; honest and upright in all his dealings, he bears an enviable reputation.

As a husband, father, neighbor and friend, in all social relations, he has been faithful and steadfast to the end. He was the only man I ever knew who understood the degradation of disfranchisement for women...

Frederick Douglass is not dead! His grand character will long be an object lesson in our national history; his lofty sentiments of liberty, justice and equality, echoed on every platform over our broad land, must influence and inspire many coming generations!

Throughout D.C. today, murals, plaques, buildings, and the Frederick Douglass National Historic Site in Anacostia at Cedar Hill allude to Douglass’s impact on the city. But to fully grasp his life and times as a Washingtonian, to get the real story as it was told while he was living, you must turn to the archives of the paper of record, The Evening Star.