American Mystery Meat: Unriddling the Mince Pie

[This article by the late Clifford J. Doerksen—who presented "bad news from the past" in his dark and witty blog, The Hope Chest—appeared in the November 2010 issue of The Readex Report. A brilliant historian and critic, Cliff died unexpectedly last month at the age of 47. Remembrances from his many fans and friends can be found at the Chicago Reader. ]

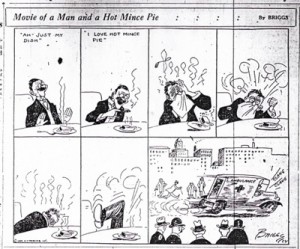

I first became attuned to the historical enigma of mince pie in the mid-1990s while doing research for my book American Babel: Rogue Radio Broadcasters of the Jazz Age (University of Pennsylvania Press: 2005), a study of forgotten independent (i.e. non-corporate) radio stations of the 1920s and early '30s. This was way back in pre-digital times, and I was spending countless hours at the helm of a microfilm reader, blindly trolling through the period press for references to my subjects. My progress would have been slow even if my magpie brain hadn't been continually distracted by newspaper stories and memes unrelated to my task. Chief among said distractions were references to mince pie. These I found everywhere, and always in contexts that baffled me. I still have photocopies of two exemplary items. One is a 1924 cartoon entitled “Movie of a Man and a Hot Mince Pie,” which depicts a middle-class diner in a pince-nez happily tucking into a steaming slice of mince, then going into convulsions and being whisked away in an ambulance.

The other is a 1925 profile of a doughty centenarian bearing the headline “At 107 She Is Fond of Hot Mince Pie.”

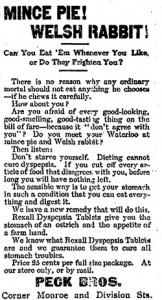

After photocopying these, I disciplined myself to stop collecting minceabilia, but I continued to find it everywhere. All I could infer from what I read was that newspaper readers in the 1920s found mince pie inherently funny, obscurely dangerous, and perpetually newsworthy. When eyestrain or a numbed bum compelled me to take a break from the microfilm room, I would sometimes visit the section of the library where books on food and the history of food were kept, there to look up “mince” in the indices of books with promising titles. The only thing I learned this way was that the pie filling we now call mincemeat had once been prepared with actual meat—usually chopped beef and beef suet—in addition to the ingredients still standard today (apples, raisins, currants, spices, citrus peel, brandy, molasses, etc.). The time came when I needed to stop researching and write a book before my allotted three score and ten ran out. I put the riddle of mince pie on a back shelf in my mental pantry, and there it sat for fifteen years. In that interim, digital newspaper archives came into the world. This was a bitter development to anyone who had done historical work with newspapers in the waning days of the old dispensation, but it more than compensated me by unlocking the mysteries of mince pie with just eight simple keystrokes. The America's Historical Newspapers database, for example, yielded 246 responses to headline searches of the term “mince pie” and 6,037 responses to “full text” searches. Aided by such wizardry, I've lately learned far more about mince than I can condense into the space available to me here. (I've written about the subject at greater length for the Chicago Reader and at my history blog, The Hope Chest.) In brief, however, here is what any self-respecting student of American cultural history should know about mince pie before they feel entitled to dessert. From the mid-19th century through the 1930s, it was mince rather than apple pie that signified as Americanism on a plate. Long before the phrase “as American as apple pie” entered the vernacular, mince was apotheosized as "the great American viand," "an American institution," and "as American as the Red Indians.” A year-round staple in every section of the country settled by whites, it could be served with equal appropriateness as an entree or a dessert. In its native New England, it also qualified as breakfast. Its popularity notwithstanding, mince was also understood to pose a terrible menace to the eater's physical, mental, and even spiritual health. In addition to being notoriously difficult to digest, the pie was known to cause nightmares, disordered thinking, hallucinations, and even death. The aura of danger surrounding mince has complex origin born out of the theological tumult of the Protestant Reformation. It was widely accepted as historical fact among 19th-century Americans that mince pie had been legally banned by the Puritans in both Cromwell's England and early colonial New England. The story was actually a hoax (which I myself fell for in a previous essay) perpetrated by one Rev. Samuel Peters, a vengeful Tory whose whopper-filled 1782 General History of Connecticut was a score-settling libel against his triumphant Revolutionary enemies. But Peters didn't have to invent the link between mince pie and the sectarianism. The Puritans hated Christmas, which they regarded as a pagan festival, and the traditional association of mince and Christmas was ostensibly enough to cast the dish into disrepute among them. I have yet to determine the extent to which early New England settlers actually eschewed the pie itself, but anti-Puritan satirists in both England and America gleefully pounced on the dish as the default symbol their enemies' fanatical rejection of earthly pleasures, and it remained a taboo food for Protestant clergymen throughout its long reign as America's national dish. A second tributary to mince's evil mystique was the gooey indeterminacy of its contents. A fine example of this trope may be found in a shaggy dog tale from the Gloucester Democrat for March 29, 1836, in which a “Doctor of Physic” mischievously chops up his old leather breeches and feeds them in mince pies to envious rivals, the latter having written off his superior healing skills to the drugs absorbed by his crusty trousers over years of use. “There was a richness, a singular mode of construction which rendered [the pie] exquisitely agreeable to the palate,” wrote the anonymous author. “We are physic-ed with a vengeance!” cried the diners upon revelation of the prank. Already associated with mince when it was a home-made commodity, mystery-meat jokes like this achieved far greater currency in the latter 19th century as the labor of making mince was outsourced to commercial bakeries, restaurants, and canning factories. By the turn of the century, pre-fab mince was the default journalistic metonymy for the decline of decent home-cooked food in an increasingly industrialized world. Concurrently, the rising temperance movement made its own contribution to mince's bad-boy image. The bibulous Puritans, who started their days with a bracing eye-opener, wouldn't have dreamed of objecting to mince's alcohol content, but by mid-century the cold water set had identified the boozy pie as a dangerous gateway pastry and shunned it even more absolutely than contemporary diet reformers like the Fletcherites and Grahamites. Following the passage of the national Dry Law in 1919, gourmands in the dissenting Wet camp decried “18th Amendment pie” as a travesty on the true article. And when national catering and liquor interests launched their 1922 legal fight for a culinary exemption to the alcohol ban, they built their case almost exclusively in terms of the dining public's right to an unexpurgated slice of mince. They won the case handily. Heavily spiced and mysterious in content, mince pie was known to reliably cause dyspepsia, a trait that all but guaranteed it a cameo in advertisements for patent digestive remedies.

Grand Rapids Press, November 25, 1903

Indigestion in turn was considered the commonest cause of nightmares, and mince, along with lobster, welsh rarebit and donuts, was ubiquitously convicted of stimulating bad dreams. But unlike the latter three foods, mince's reputation for psychotropic side effects extended to the diner's waking state. As an essayist for the Bismarck Daily Tribune put it in 1889, “Mince pies, when made of mince, are less harmful than those mince pies not made of mince; but mince or no mince, they do more thinking for a man than any other kind of pie, and are therefore the intellectual pie par excellence.” Most references to mince's hallucinogenic properties were meant as jokes, e.g. film critic Mae Tinae's judgment that the 1920 German expressionist masterpiece should on no account be hazarded while under the influence of mince. On occasion, however, perpetrators of violent crimes made serious efforts to extenuate their actions by claiming that mince made them do it.

Trenton Evening Times, February 13, 1909

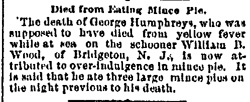

At its most malignant, mince pie was known to kill the eater outright. Such was the fate ascribed to one George Humphreys, who died at sea in 1888 one day after gluttonously consuming three entire mince pies at a sitting.

Philadelphia Inquirer, December 11, 1888

In the Teens and Twenties, some medical authorities worried that the populace as a whole was poised to follow Humphrey's suit, owing to cumulative “race deterioration” caused by “the armor plate mince pie diet indulged in by all America.”

As dangerous as it was, Americans continued to dote on mince as their national dish until suddenly abandoning it after World War II. How and why the pie lost its protein content and got banished to the seasonal ghetto of the Christmas sideboard overnight is a mystery I have yet to solve. Conceivably this sea change in the national diet may have stemmed from risk-averse cultural tendencies accompanying the greater material prosperity of the post-war period. In this connection, it's worth considering the words of poet and essayist Eugene Field, who in 1888 declared (paraphrasing Alexander Pope): “Custard is the pie for boys, pumpkin for men; but he who aspires to be a hero must eat mince!”

About the Author

Recipient of a 2010 James Beard Award for Best Newspaper Feature on food, Cliff Doerksen is Chicago-based film critic, journalist, blogger, historian and home baker. He's currently working on an entire book about mince, if you please.