The "Sensational, Hair-Raising, Blood-Curdling, Penny-Awful" American Life of Ned Buntline

What activities might make up the archetypal life of a 19th-century American man? Items on such a checklist could include:

Samuel Clemens checked off many of these items: He was a sailor, if on the Mississippi. He went west to make his fortune. He had served briefly in the Civil War. He was a journalist and popular lecturer. He reinvented himself as the author Mark Twain. He became an entrepreneur, and he lost a fortune.

Ned Buntline (1821-1886) from Early American Newspapers

However, my vote for the individual representing the epitome of a 19th-century American life goes to Ned Buntline. Buntline checked off every one of these items during the arc of his life, which can be followed through Readex’s Early American Newspapers. To begin with—Ned Buntline was not his name. He is born Edward Zane Carroll Judson in 1821 and becomes known as E.Z.C. Judson before adopting his pseudonym. He runs away to sea as a cabin boy, and then serves on a naval vessel. His personal bravery gets him promoted from the ranks to midshipman. When other midshipmen look down upon him, he fights duels with each of them. He serves in the Seminole Wars, but doesn’t see combat. And then his life gets interesting. This article lists him as a midshipman.

Charleston (SC) Courier (April 11, 1838)

He becomes a journalist. His early reporting about New York City and its slums appears in the serialized The Mysteries and Miseries of New York, which is widely reprinted.

Philadelphia Inquirer (Dec. 30, 1847)

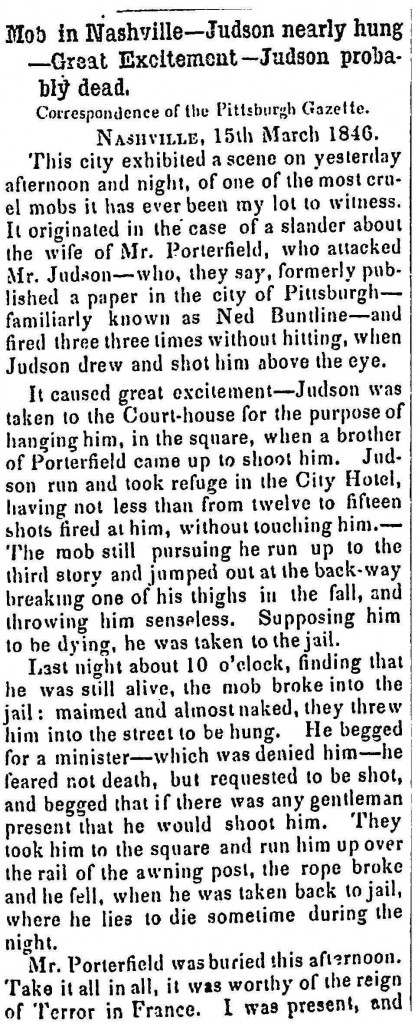

He moves west—to Ohio—and starts the Western Literary Journal and Monthly Magazine, which fails. He leaves for Kentucky, and after having apprehended some criminals and getting the reward, he moves to Nashville and starts Ned Buntline’s Own. In Nashville Buntline seduces the wife of Robert Porterfield and is challenged to a duel. Killing Porterfield, Buntline goes on trial. During the trial he is shot by Porterfield’s brother. Buntline escapes in the commotion, but is captured by a lynch mob. Surviving the mob, he is rescued, and his indictment for Porterfield’s murder is dropped. Now its 1846 and he’s all of 25 years old. You’d think the quiet life might have beckoned, but he’s Ned Buntline! This is an article in which the headline says it all:

Washington (D.C.) Reporter (March 28, 1846)

He moves his newspaper to New York. Some noteworthy things happen during this stint in the big city. He’s publicly horsewhipped by a brothel madam.

New Hampshire Patriot and State Gazette (April 12, 1849)

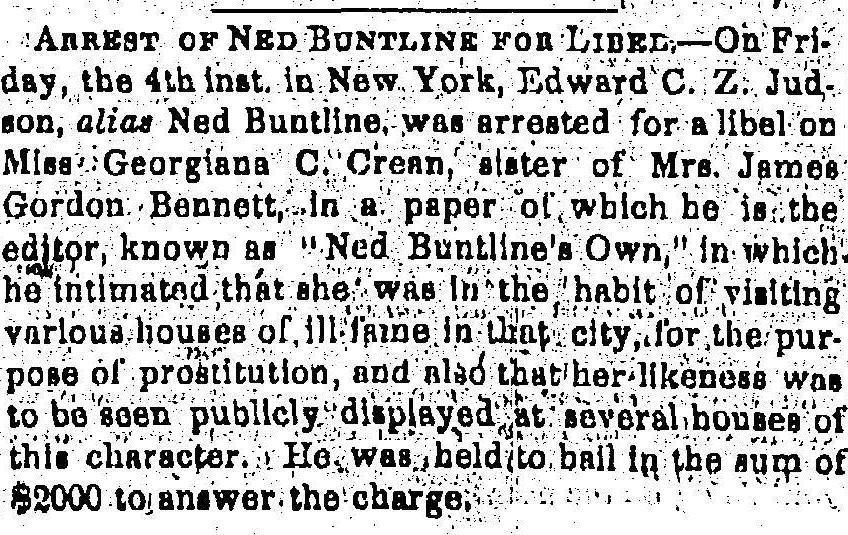

He gets sued for libeling the sister of James Gordon Bennett, publisher of the influential New York Herald.

(New Orleans) Daily Picayune (May 14, 1849)

And he gets involved in the Astor Place riots, also known as the Shakespeare riots. English actor William Charles Macready and American actor Edwin Forrest each had their own fans. English actors were high profile visitors to this country and were often the focus of anti-British sentiments. Fans of these actors proclaimed each the best of their time, especially in Shakespearean roles. Nativists and Irish immigrants, not the most natural allies, supported the American. Citizens of a higher class liked Macready. Forrest and Macready had a professional rivalry, and then, in 1849, they both performed Macbeth in theaters only blocks apart. There had been violence, booing and objects thrown on the stage at Macready’s performance, and he had proclaimed he would be taking the next boat home. But he was persuaded to stay and perform again. Nativists planned to pack the house with their own supporters. Thousands of people showed up and filled the streets around the theater. The authorities had put extra police into the neighborhood and stationed the militia. The police were needed, as a riot broke out, but were not sufficient. The militia were called in and eventually began firing, in the air, and then at the crowd. Buntline is arrested.

(Boston) Daily Evening Transcript (May 11, 1849)

Unlike most of those arrested, Buntline has a paper and can publish his side of the story.

Maine Cultivator and Hallowell Gazette (May 19, 1849)

Later he gets beaten up in Philadelphia.

(Boston) Daily Evening Transcript (July 5, 1849)

He eventually goes to jail and is released after a year. He’s not yet 30 years of age. The text of the article discussing his release is worth quoting in full, because it gives the flavor of the newspapers of the era and also shows the disdain some felt about Ned Buntline.

The entrée into the city of ‘Ned Buntline,’ alias E.Z. Judson, of Opera House Riot memory, after serving a year’s apprenticeship at Blackwell’s Island, was duly celebrated by his friends and associates yesterday afternoon. They turned out to the number of about five hundred, and escorted him through some of the principal streets, with a band of music. Ned was drawn by a ‘coach and four.’ It is supposed that after his decease he will be canonized. New York Journal of Commerce.

(Boston) Daily Evening Transcript (October 3, 1850)

Ned’s going to live until 1886. He’ll need a heck of second act. And he’ll get it. And it’s covered in the papers. It’s like he’s a 19th-century Kardashian.

Somehow in 1851, after it was reported that he would be part of an invasion of Cuba, Ned’s found lecturing about the island, appearing in full Patriot costume and with a Cuban flag.

(Wash., D.C.) Daily National Intelligencer (Sept. 20, 1851)

He moves his paper to St. Louis where he gets accused of fomenting an Election Day riot. He is arrested, indicted and returned to jail.

Daily Alabama Journal (April 28, 1852)

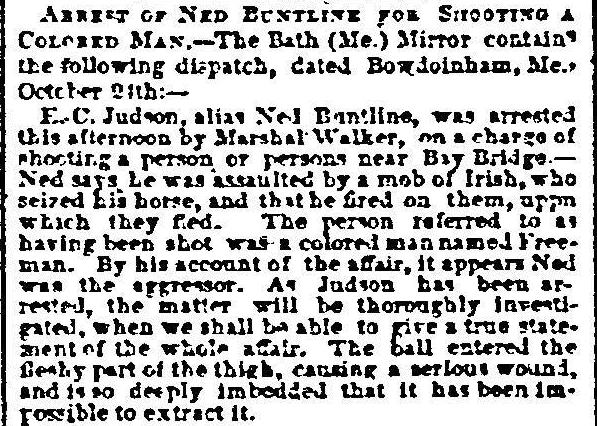

Later, in Maine, he claims that he was set upon by a mob of Irishmen who don’t agree with his Know-Nothing philosophy and, protecting himself, he shoots a colored man, who claimed Buntline started the affair. He gets acquitted.

The (Baltimore) Sun (October 27, 1854)

In 1857 it’s reported he’s become a spiritualist.

Delaware State Reporter (January 2, 1857)

By 1860, an article headlined “What Has Become of Ned Buntline?” explains that he’s living the good life in upstate New York.

Washington (Penn.) Reporter (September 20, 1860)

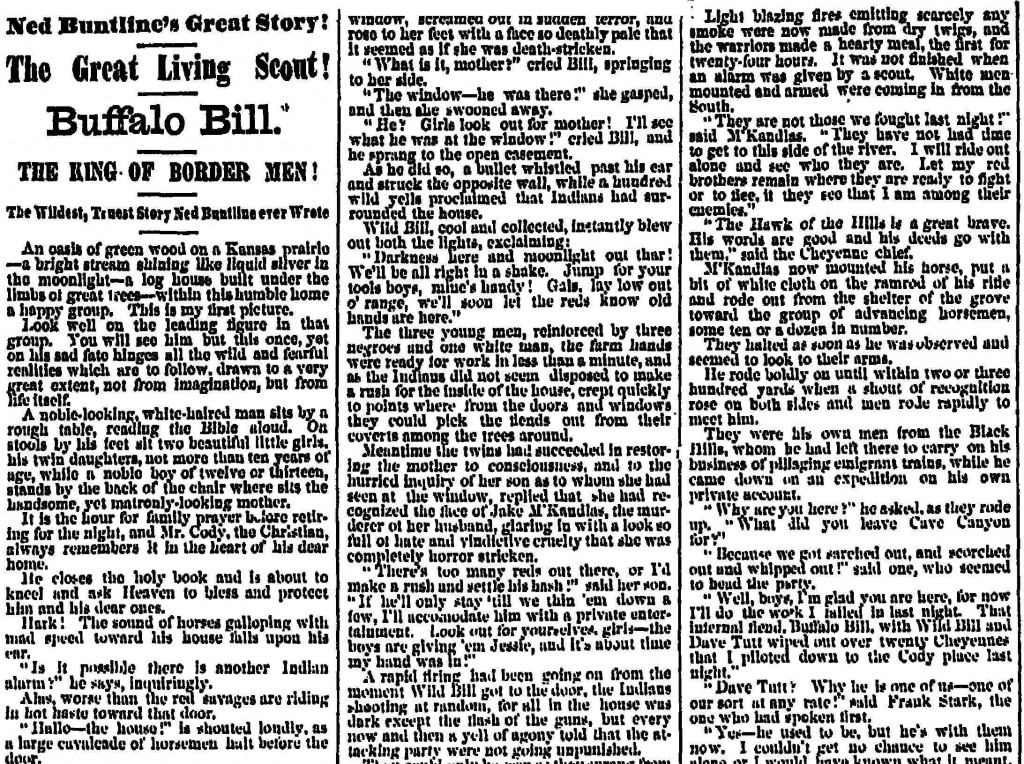

When war comes, he joins the New York Mounted Rifles. Six months later it’s reported he has been imprisoned for desertion. He’s in his forties now, and nothing described above is why he’s remembered today. He’s remembered for what comes after the war, which begins when he meets Buffalo Bill. In later life, Buntline would claim to have given him the nickname. We do know Buntline wrote one of the best dime novels about Buffalo Bill.

Albany (NY) Journal (December 14, 1869)

Buntline’s novel is a huge success. It is dramatized a few years later, and the play is a great success as well. This leads Buntline to write his own play, The Scouts of the Prairie, which stars Buffalo Bill himself, as well as Texas Jack Omohundro. Buntline also appears in it. Real Indians are also part of the cast, and this play is a great success, too. This amusing review appears in the New York Herald:

The drama, of which we understand Ned Buntline is the author, is about everything in general and nothing in particular….Mr. Judson (otherwise Buntline) represents the part as badly as it is possible for any human being to represent it and the part is as bad as it was possible to make it. The Hon. William F. Cody, otherwise ‘Buffalo Bill,’ and occasionally called by the refined people of the Eastern cities ‘Bison William’ is a good-looking fellow, tall and straight as an arrow, but ridiculous as an actor. Texas Jack, whose real name, we believe, is Omohundro, is not quite so good-looking, not so tall, not so straight and not so ridiculous….Senorita Carfana...is worse, even, than Ned Buntline, and he is simply maundering imbecility.... The entertainment began with a farce by Ned Buntline called ‘The Broken Bank,’ probably the worst ever written, and certainly the worst acted atrocity ever seen on any stage.

New York Herald (April 1, 1873)

This was Buntline’s peak. He continued writing. He continued to be of interest to newspaper readers until his death in 1886, reported below in The Kalamazoo Gazette.

The Kalamazoo (Mich.) Gazette (August 1, 1886)

For more information about Early American Newspapers, please email readexmarketing@readex.com.