The pure-bred New Englander revered the Constitution. Though the eloquent statesman hated slavery, he sought to eradicate this evil without destroying the union. Division was anathema to him, as could perhaps be guessed from his ancestral name, Webster, which means “uniter” in Anglo-Saxon. And some three score and eight years before the outbreak of the Civil War, whose 150th anniversary we commemorated last spring, he advocated a moderate course designed to steer clear of bloodshed.

The man’s first name was Noah—not Daniel—and he hailed from Hartford. While his younger cousin, the Massachusetts legislator, would repeatedly take up the same mantle on the Senate floor, most notably in an impassioned speech on behalf of the Missouri Compromise in 1850, Noah Webster first spoke out against “the violated rights of humanity” back when Daniel was still in grade school.

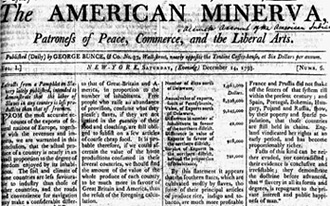

At the time of his death in 1843, Noah was the more famous Webster. After all, with his legendary speller first published at the end of the Revolution and his massive dictionary completed a half century later, he gave us our official language—American English. Moreover, this prolific writer was more than just America’s answer to the great British lexicographer, Samuel Johnson. In the mid-1780s, as George Washington’s personal policy advisor, he authored a series of influential essays in support of America’s founding document. A decade later, at President Washington’s behest, the Webster, whom Daniel once dubbed the “true likeness” of the clan, became the editor of New York City’s first daily newspaper. However, by the 1940s, when Daniel Webster was cross-examining the Devil in the Hollywood version of Stephen Vincent Benet’s short story, the Connecticut Webster was largely forgotten. Daniel, most Americans began to assume, must also have been a wordsmith.

American Minerva, and edited it for four years.

Source: America’s Historical Newspapers

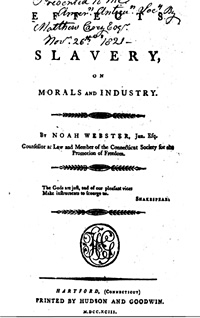

During the economic downturn of the early 1790s, while toiling as a lawyer in his hometown, Noah Webster joined the fledgling Connecticut Society for the Promotion of Freedom. In the first wave of the antislavery movement, similar abolition groups cropped up in states from Massachusetts to North Carolina. In 1793, at the Connecticut society’s annual meeting, Webster delivered a memorable speech, “Effects of Slavery on Morals and Industry,” later expanded into a widely disseminated 56-page pamphlet.

for Webster's influential anti-slavery pamphlet.

Source: America’s Historical Newspapers

To issue yet another moral condemnation of slavery, Webster felt, would be an insult to the “understandings of my enlightened fellow citizens” of Connecticut. Instead, he crafted a carefully nuanced argument, which emphasized how the barbaric institution dehumanized everyone. “The exercise of uncontrolled power,” he noted, “always gives a peculiar complexion to the manners, passions and conversation of both the oppressor and the oppressed.” Citing mountains of demographic data, Webster also maintained that slavery would continue to be a drain on macroeconomic productivity. In America where 700, 000 of the four million inhabitants were then slaves, exports per capita were about two thirds of the comparable figure in Great Britain where slaves had never comprised more than a tiny fraction of the population. “Men will not be industrious,” this keen observer of human nature concluded, “without a well founded expectation of enjoying the fruits of their labor.”

Source: America’s Historical Imprints

As fervently as Webster wanted to rid his country of this scourge, he advised caution. “An attempt to abolish it [slavery] at a single blow,” he warned, “would expose the whole political body to dissolution.” To hammer home his point, he footnoted Cicero’s contention that “a remedy which cures the diseased parts of the state should be preferable to one which amputates them.” To heal America, Webster proposed a two-pronged solution. For the eight states north of Delaware, which then housed a total of only 40,000 slaves—four fifths of whom resided in New York and New Jersey—he recommended gradual abolition. For the six southern states, he urged plantation owners to “raise the slaves, by gradual means, to the condition of free tenants.” This policy, he was forced to concede, was far from satisfactory, as it probably would not translate into freedom for generations. However, given that the ratio of slaves to free inhabitants was a staggering 1 to 2.5 throughout the south, the Connecticut scribe saw no other “method for meliorating the condition of the blacks without essentially injuring the slave, the master and the public.”

While Southerners, of course, ignored this New Englander, Northerners paid close attention. Several years later, prodded by Webster’s Federalist party ally, Alexander Hamilton, who wrote frequent editorials for his paper, the New York legislature passed a law whereby all male slaves born after July 4, 1799 would be freed upon their 28th birthday. By 1804, every northern state, which hadn’t already outlawed slavery, had passed such a gradual emancipation law. In 1828, to illustrate the meaning of the term in his dictionary, Webster could proudly assert, “Slavery no longer exists…in the northern states of America.”

Soon after the publication of his “great book,” the abolition movement, which had lain dormant for decades, made a comeback. This time around, its leaders such as William Lloyd Garrison demanded immediate emancipation. By then, Noah Webster was in his 70s, and he feared a radical shake-up of his country more than ever. Of New England’s second generation of Abolitionists, he wrote in 1837: “They are absolutely deranged….slavery is a great sin and a great calamity, but it is not our sin.”

Given the bloody carnage that was to follow a quarter century later, the trepidation about taking decisive action expressed by both Websters was not entirely unwarranted.