For most present-day racetrack goers, it seems unlikely that a horse named Eliza Wharton might cause a flash of recognition, a knowing smile, or a startle at the potential impropriety. But for nineteenth-century racing fans, this was not the case.

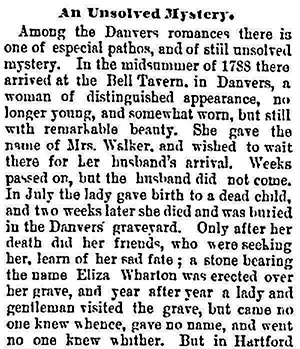

“Eliza Wharton” was the heroine of Hannah Webster Foster’s 1797 best-selling novel, The Coquette, loosely based on a New England scandal of the previous decade involving Elizabeth Whitman, the daughter of a well-known minister in Hartford, Connecticut. The novel’s heroine, likewise a minister’s daughter, spurns the advances of a rather staid minister, only to succumb to the seductive wiles of a well-known rake, fall pregnant, and flee her parents’ home for Danvers, Massachusetts, where she eventually dies after delivering a stillborn child. Readers who might have been expected to condemn the fallen woman instead sympathized with her.

Why exactly the name Eliza Wharton was chosen for the bay mare, we can’t be sure: was the novel a particular favorite of her owner, Thomas Doswell of Virginia, or his wife, Susan Brown Christian? Did the horse remind them of the novel’s well-bred and refined heroine? Or was there a bawdier reason, suggesting both the horse and the novel’s heroine were “fast”? Regardless, the horse serves as a marker of the novel’s saturation in the American imaginary. It is unlikely that anyone who read its name in a newspaper of the 1830s did not immediately grasp the association.

Click to open full article in PDF.

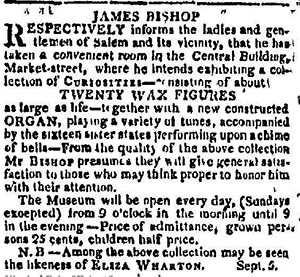

Period papers provide more clues to the novel’s popularity. Eliza Wharton gave her name to a ship from Duxbury; James Bishop’s traveling waxworks show prominently featured a figure modeled on Eliza Wharton.

Click to open full article in PDF.

Advertisements for waxworks shows which appeared up and down the coast in the first two decades of the nineteenth century made sure to feature Eliza Wharton’s name prominently. In doing so, they provide insight into how the meaning of the story of Elizabeth Whitman shifted over time. Initial reports condemned Whitman.

However, following the publication of Foster’s novel, public perception shifted. Advertisements for waxworks shows suggest Whitman/Wharton functioned as a folk hero of sorts, placed as she was among a pantheon of American heroes. Her drawing power is also evident in the events of 1812. The schooner on which Bishop was traveling with his waxworks was briefly held captive during the War of 1812, and all profits seized. Returning to the U.S., deprived of profits, Bishop immediately placed an announcement advertising his show. The fact that the only waxwork identified in that ad was Eliza Wharton suggests its ability to draw a significant audience.

If advertisements and racing pages were not enough, over the course of the nineteenth century the real-life story that inspired the novel also maintained its currency in the popular press, evident in casual asides and passing anecdotes, demonstrating its ongoing appeal. Arguments about details of the Whitman case still erupted, with contributors increasingly likely to defend Elizabeth Whitman’s honor, demonstrating even further shifts in her meaning and reception in the popular imaginary. With increasing frequency, papers reported on visitors to Elizabeth Whitman’s grave, and its current state, waxing romantically about the experience.

Click to open full article in PDF.

If literary tourism was a new phenomenon in the nineteenth-century United States, such accounts demonstrate The Coquette was one of its first indigenous organic eruptions.

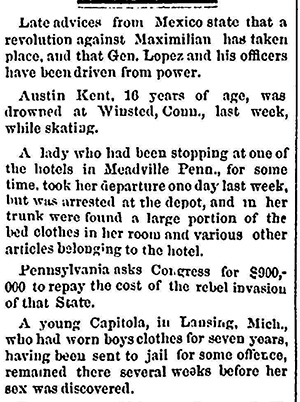

As evident in the case of The Coquette, newspapers provide more than a way to trace the circulation or sales records of a novel, as one might find in publishers’ records or library lending ledgers. Instead they initiate an opportunity to begin to understand the degree to which a novel permeates the public imaginary. E. D. E. N. Southworth’s The Hidden Hand was serialized in the 1850s, 1860s, and 1870s before appearing in book form in 1888. The heroine, Capitola Black, outwits bandits, thwarts seducers, and pre-empts patriarchal authority at every turn with a joyous insouciance that up-ends more conventional narratives of female submission.

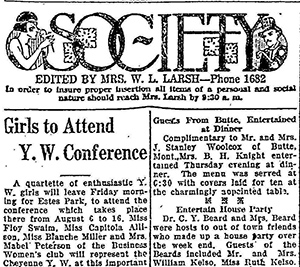

Today we might use the United States Social Security Name Tracker to determine the influence of a novel or film—the spike in children named after characters from Buffy The Vampire Slayer and Twilight in the last twenty years provide excellent markers of the works’ overall influence: Bella, Xander and Willow have all seen significant upsurges. In some nineteenth-century cases it is difficult to trace the exact influence. Were African Americans who claimed the name Madison Washington following Emancipation aware of Frederick Douglass’s 1852 novella The Heroic Slave, or were they drawing on the real-life man? Whereas The Coquette’s heroine boasted a name too common to be useful in tracing its influence, Capitola is far more distinctive. The rise in young women named after the novel’s rambunctious heroine can be traced through birth, death, marriage, and other newspaper announcements.

Click to open full article in PDF.

Miss Capitola Bassett of Okmulgee, Miss Capitola Simpson of Ashland, Miss Capitola Farmer of Fort Worth and Miss Capitola Wentzel of Harrisburg are just a few of the young women whose Christian name attests to their mothers’ shared desire for daughters who were not shrinking violets. Like Eliza Wharton, Capitola inspired other namesakes: there was a sail boat, several race horses (including another bay mare, this one bred by John E. Wood of Orange County, New York), and plumed riding hats. That a stove company borrowed the name to market its product makes less sense, given the novel’s unconventional heroine and her lack of orientation to the domestic realm. Capitola, California, may take its name from the heroine. We also learn “Capitola” became informal shorthand for young women who wore boy’s clothes.

Click to open full article in PDF.

The difference between Capitola and Eliza Wharton lies in their character and in their evolution. Capitola was from the beginning a marketable product, her purity intact, her gumption apparent. In this way her name could be attached to products—not unlike characters from Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin—because Capitola’s virtue was unquestionable. What popular media representations of her show us is that her character does not evolve over time, nor does the public interpretation of it. Eliza Wharton, a fallen woman according to both historical precedent (Elizabeth Whitman) and the script of the novel itself, could not be attached to products. But what we do see from examining media representations is that as public opinion and mores shifted, so too did readers become increasingly sympathetic to her, and increasingly less sympathetic to the character of the staid minister whom she rejected. Over time, a romantic sheen replaced lived memories of the actual scandal and its actors in the way the story is represented—less scandal and more tragedy. Identifying shifts in representations of Wharton/Whitman allows us to identify changes in reading practices of novels themselves, as well as to better understand the ways in which nineteenth-century literature was crucially constitutive of the era’s popular culture practices.