Spanish Influenza of 1918, Part 3: The Waves Continue, Jan. to Dec. 1919

As seen in Part 2 of this series, U.S. newspaper coverage of the Spanish Influenza ended 1918 on a relatively positive note. On New Year’ Eve the San Jose Mercury News reported:

The conditions for San Jose and adjoining territory seem to be on a direct road to improvement as far as influenza is concerned….At all the local hospitals, the conditions were reported as better, nearly all those ill were doing nicely and the percentage of new cases had dropped to a very small number.

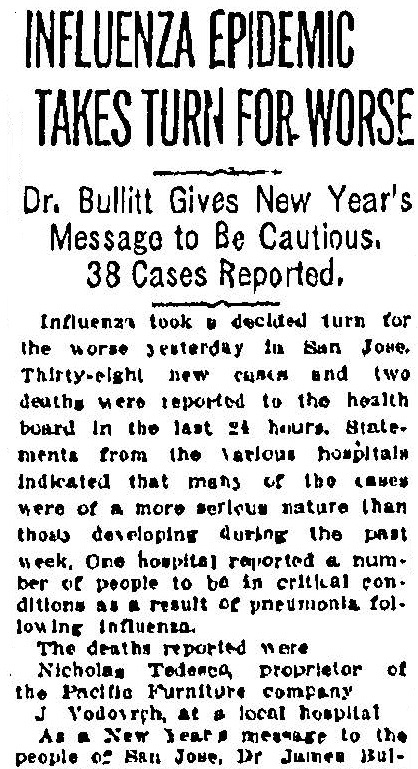

The next day, January 1, 1919, the same paper’s headline was “Influenza epidemic Takes Turn for Worse….38 Cases Reported.” Dr. James Bullitt, San Jose’s health officer warned “last night that a great deal of precaution must be observed in homes where cases of the disease exist….that the number of pneumonia cases developing each day is on the increase…”

The epidemic was far from tamed in Boise, Idaho, which, like many communities across the nation, was pursuing a vigorous campaign to enlist volunteers to relieve the burden of providing for the ill. The Jan. 2, 1919, issue of the Idaho Statesman asked:

Are you in need of a nurse, hot food, medical supplies, laundered clothes, or practical help around the house? Are you willing to volunteer your services to the Red Cross as a practical nurse or handy man? Are you willing to donate the use of your automobile for delivering hot food, medical supplies, or other aid to homes affected with influenza?

The Statesman further reported that:

Food desired for the present will be cooked at the high school cafeteria, under the supervision of Miss Stevens, who is domestic science teacher for the school….and it is her intention to have, if possible, the advanced domestic science class of the high school (consisting of 12 pupils) aid her in preparing and cooking the food.

Further:

Mrs. C.C. Anderson has donated her automobile and chauffer for morning deliveries, and the home service section is hoping that more people will come forward with the loan of their cars for this purpose.

Because of the proximity of Rhode Island to Boston and the U.S. Army’s Camp Devens, it was not surprising that the epidemic struck there in September 1918. That outbreak appeared to have abated by the end of October. However, on Jan. 2, 1919, the Pawtucket Times announced “Influenza Epidemic Getting Dangerous. State Officials May Place Ban on Gatherings if It Increases Much.” A second wave had arrived.

Parts of South Carolina were inundated by influenza in the autumn of 1918. By Jan. 3, 1919, the “physician in charge of influenza control” was able to report on what was experienced. Dr. Aiken provided a county-by-county account that divided the deaths between white and black citizens. His statistics starkly demonstrated that black deaths significantly outstripped the fatalities white people had suffered in all but a handful of counties. Aikin wrote:

Nations and states and even individuals have always paid a heavy tribute for unpreparedness….More than 4,000 lives will have been wasted and untold suffering experienced in vain if the people of this state do not make immediate and everlasting use of the terrible lesson so pointedly expressed by the helpless condition into which they were thrown when influenza struck a population, 90 per cent of which was without adequate health organization.

Patent medicine purveyors continued to seek profit from calamity as evidenced by an item in the Jan. 4, 1919, issue of the Philadelphia Inquirer. Under the headline “Influenza Again Is A Serious Menace” and the sub-headline “You Can’t Be Too Careful If You Have A Cold—Treat It Promptly With Father John’s Medicine,” the piece accurately reported that a second wave of influenza in the U.S. “has returned with full vigor and in some places is even worse than during the fall.” However, the item then devolved into a promotion of Father John’s Medicine. The implication was that this mixture would help stave off influenza as well as ameliorate its effects on the user. In fact, it could not serve as a prophylactic nor a cure. It was a cough medicine, a palliative, consisting largely of cod liver oil and licorice root.

The term “social distancing” was not extant in 1919, but the prohibition on public gatherings, the closing of bars and amusements and schools, all imposed a distancing among people however haphazardly. There emerged evidence that premature relaxation of these strictures often caused a resurgence in the number of influenza cases.

On Jan. 5, 1919, the Oregonian wrote that “276 cases were reported to the health bureau with 10 deaths for the last 24 hours.” The Acting City Health Officer stated “There is no question in my mind that the present increase is due to the people mingling in crowds during the holidays.” The officer also…

…believes it is probable that many cases have existed in Portland during the last month which have not been reported. The populace, he states, now realizing the necessity of isolation of cases, are reporting…to the health bureau, thus increasing the number of new cases reporting.

The Bellingham Herald in Washington state reported on Jan. 9 that the “Influenza Epidemic Worse in California” where San Francisco’s health officer appealed to the public “to wear gauze masks….in view of the increase in the number of influenza cases.”

By Jan.11, 1919, the Twin Falls Daily News in Idaho headlined an article “Influenza Epidemic Rages In Coast Cities” which announced that

…dancing was ordered stopped in Multnomah county [Portland, Oregon] today on account of the influenza epidemic. Visiting in hospitals was also banned. Two hundred and seventy-three cases were reported Friday. The deaths totaled 19. Vaccination stations will be established today in various parts of the city so that persons who desire may be inoculated without cost.

The first influenza vaccine licensed for use in the U.S. was not available until the 1940s, but throughout the 1918-1920 epidemic, many scientists were striving to create an effective vaccine. Presumably, it was one such effort that was being offered in Portland.

The disease affected rural communities as well as urban. Wendell, Idaho, had a population of approximately 600 in 1919. On Jan. 14 the Twin Falls Daily News reported on one doctor’s “Strenuous Week in Wendell.” Captain White had

…spent the preceeding [sic] seven days and nights without the assistance of another physician in attendance upon influenza patients and in forming an organization for the care of sufferers from that district…[where] there were 150 cases of influenza, and the only physician of the district was himself a sufferer from the epidemic.

Two days later the same Idaho newspaper ran a story indicating that local decisions about public policy dealing with this contemporary plague were scattershot and not always comprehensible. In Portland, Oregon, the city council was unable to mandate the citizens to wear masks because a “unanimous vote for the measure was required to make it effective at once” and a sole commissioner “refused to vote for the ordinance.” The article notes that “Three hundred and fourteen new influenza cases were reported here yesterday.”

Perhaps several of those new cases were Frank Johns and his grandchildren, all of whom died days later as reported by the Idaho Statesman.

The family of Frank Johns, formerly of Boise, has been hard hit by the influenza, according to the Portland Telegram, which tells of the death of five members of the family in 24 hours from the dread disease.

The grandfather was 63, and the grandchildren “whose deaths leave their parents…childless,” were between ages 6 and 12.

The Montgomery Advertiser of Alabama estimated that “four hundred thousand persons have died in America from influenza since its appearance in a virulent form, early last fall.” Under the headline “Mysteries of the Influenza Epidemic” on Jan. 22, 1919, the paper reported that

…the old-line insurance companies, which keep exact statistics, have paid out in death claims, made for persons who died of influenza, a total of sixty-five billion dollars.” [It was likely million, not billion.]

One of the mysteries was the astonishing death rate among temperate young adults.

In an analysis of a number of claims paid in the early days of the epidemic, the fact was brought out that among insured lives eighty per cent. of those who had died were under forty years of age and sixty per cent. under thirty-five. The same investigation showed that of the claims considered about two-thirds were teetotalers and one-third temperate.

Not surprisingly, but sadly, medical personnel were endangered by their jobs. On Jan. 26, the Dallas Morning News reported that “Enrolled nurses of the Red Cross numbering 204 died since the inception of the influenza epidemic…”

Minority populations including blacks, American Indians, and aboriginal people of Alaska, commonly referred to as Eskimos, were disproportionately affected by the disease. “Eskimos Stricken with Influenza. Epidemic Reported to Have Cut Down Flower of Race In Many Sections,” announced the San Jose Mercury News on January 27. The tenor of the times allowed racism to infuse even sympathetic reportage.

Probably the highest type Eskimo of the north resided in the village of Cape Prince of Wales on Bering straits, where a population of 350 natives has been reduced to 36 adults and 100 children. This farthest west community in the American continent showed the Eskimo at his best. There was not a single white man there.

On February 3, 1918, the San Jose paper ran the headline “Influenza Epidemic Fatal to Indians.”

The epidemic of influenza sweeping over Humboldt country is proving particularly fatal to the Indian families along the Eel river.

In Portland influenza had come in two waves. With apparent relief, the Oregonian reported on Feb. 11 that “Health Officer Proclaims End of Epidemic. Second Wave of Influenza Wanes…”

Little more than a week later the same newspaper’s headline was “New Epidemic Is Feared. Twelve More Cases of Influenza Are Reported During Day.” The city health officer was cautiously optimistic

…that if all residents of the city will take ordinary precautions as were suggested during the two previous epidemics a third flare-up might be avoided.

Spanish Influenza was a pandemic internationally. Hence, events abroad had implications domestically. On Feb. 24, the Oregonian reported that “Epidemic Grips Britain. Influenza again Sweeping Over United Kingdom.”

Two days later the Oregonian’s headline read “Spain Has New Epidemic. Influenza Reported to be Spreading in Alarming Manner.”

Second and third waves of influenza were occurring in diverse locations. Twin Falls, Idaho, was one such place. The Statesman on March 18th wrote

As a means of caring for patients during what seems to be a recurrence here of the Spanish influenza epidemic the county commissioners Monday, upon advice of the county Red Cross executive board, reopened the emergency annex to the county general hospital, which was closed about two months ago when the first wave of the influenza passed.

By March 29 the Surgeon General’s dire prediction, made late in the preceding December, was reiterated by the Baltimore American which re-ran an article from the Rocky Mountain News.

Surgeon General Blue is quoted as looking forward to a very serious return of the influenza next year [1919], and members of the National Health Association, while in session in Chicago a few weeks ago, placed the expected mortality as high as 750,000…

The pandemic continued apace in other countries. The Charlotte Observer of North Carolina ran a reprint from the London Times-Public Ledger Service reporting that six million people had died in India as a consequence of influenza.

The wave theory gained credibility as the Statesman reported on April 18.

London scientists who are observing the operations of Spanish influenza say that, so far as the British isles [sic] are concerned, it moves in waves….The disease first made its appearance here last July, and began to subside toward the end of August. Eight weeks later, in October, it reappeared, and by the middle of November had apparently run its course. The third wave came in January, and by the early days of March had apparently done its worst.

The situation in Alaska grew so dire that

…naval ships carrying surgeons and large quantities of medical supplies have been dispatched to the Bristol bay region…to combat an epidemic of influenza which threatens about 5,000 persons, most of them employed in the salmon canning industry.

A hospital ship was due to “leave Charleston, S.C., Monday for San Francisco and if the epidemic is not under control when she reaches the west coast the vessel will be ordered to Alaska.”

A brief article in the Belleview News Democrat of Illinois reported that some congressmen were urging the federal government to set aside appropriation in anticipation of another wave of influenza.

The last epidemic caused 500,000 deaths and an economic loss of $4,000,000,000, according to figures compiled by the American Medical Association…

Some of these costs were being absorbed by hospitals risking their financial stability. Colorado Springs had suffered significantly during the epidemic. On August 9, 1919, the Colorado Springs Gazette announced that a tag sale to support the local hospital would be held.

Pretty girls, chaperoned by prominent matrons of the city, will be in lobbies of the hotels, at the soda springs in Manitou, at the post office and other buildings and on the street corners with a tag for each passer-by and their hands out for money.

The reason was that they had been unable to hold their “customary bazaar by means of which the financing of the institution is usually given a boost could not be held last winter because of the influenza epidemic.” Further, not all the patients treated at the hospital “were paying cases, and there is still a large sum owing…”

“New Epidemic of Influenza Feared” warned the San Jose Mercury News on September 10. The state board of health had issued a statement:

If we are to judge by previous experience with pandemics of influenza we may expect that there will be a recurrence of the disease in epidemic form this winter, but not in so severe a form, or so extensive.

The warnings did not go unheeded. According to the Sept. 19th issue of the Colorado Springs Gazette:

In an effort to be prepared should there be a recurrence of the influenza in Colorado Springs during the coming winter, the city health department is now making preparations for the establishment of an emergency hospital at the National hotel in West Colorado Springs, and for the manufacture of influenza vaccine at the city laboratory.

By October 1919 it appeared that such planning was prudent. On Oct. 3, the Aberdeen Daily News reported that the epidemic had returned with many cases reported in the east and three in Aberdeen.

The warnings became gloomier as reported by the Cleveland Plain Dealer on Oct.18.

Declaring that people gained nothing from their experiences with the ailment in 1918 and 1893, Dr. W.A. Evans, health authority and writer of Chicago, today predicted that the world would be swept by an epidemic of influenza far more severe and disastrous than last year when thousands of lives were lost.

The doctor seemed to harbor some ill-informed convictions as to the origins of the disease.

One group of scientists who have studied this disease and the ailments that constitute it, contend that its home is in foreign countries and that it was brought to this country by immigration…Among the homes of the poorer classes of people it has flourished and gained remarkable headway.

The Idaho Statesman, which had provided solid reportage of the epidemic from early days, reported on November 9th that the state medical expert described how influenza cases increased exponentially with one case swelling to “729 cases by the twelfth day.” He also suggested ways to stay healthy—isolation, avoidance of the ill, coughing into a handkerchief, and a new addition: “Wash your hands frequently and don’t put them to your lips or mouth.” He asserted that “Gargles have little or no merit and wash the protective secretions from the throat.”

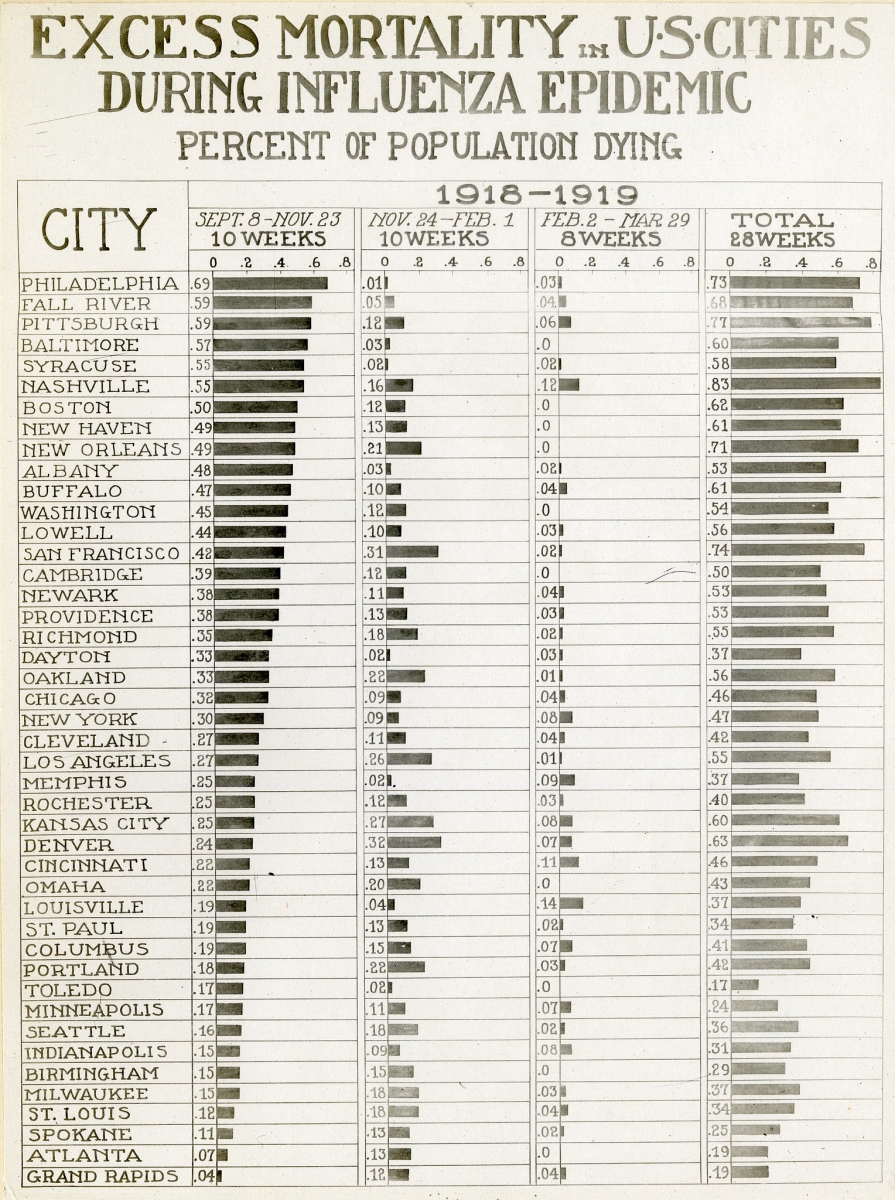

As 1919 drew to a close, the prospects for the new year were fraught with trepidation. Nearly a half million Americans had died because of the pandemic. It had become accepted wisdom that this epidemic had come in waves throughout the world. What no one could confidently predict was the likelihood of more waves to come and how lethal they might be.

For information on bringing Early American Newspapers, Series 1-16, to your institution, please contact Readex.