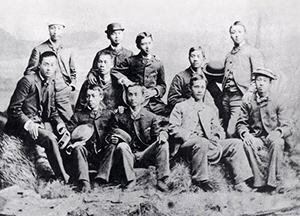

In September 1872, Yung Wing escorted a delegation of young students from China to Springfield, Massachusetts, under the auspices of an unprecedented enterprise—the Chinese Educational Mission. Wing’s all-male contingent attracted attention throughout the United States. Rumors had circulated for months that in order to bring its isolated nation into the 19th century, the Chinese government would finance the American education of gifted children. The Hartford Daily Courant (May 7, 1872, p. 5) explained that “Mr. Wing has finally…prevailed upon his government to select thirty boys each year for the next five years…through which China should be able to profit by an acquaintance with the ways of modern civilization.”

Often described by journalists as the young Celestials, the boys, none of whom was older than 14, would achieve high rank working for Chinese authorities upon completion of their studies upon completion of their studies. The students endured a six-week voyage across the Pacific Ocean and a lengthy train ride from San Francisco to their New England destination. They were disbursed from Springfield to host families throughout Massachusetts and Connecticut. Prominent citizens were selected to welcome the Chinese boys into their homes and provide a period of home schooling. When the students had sufficiently grasped the English language and become acclimated to American culture, they would proceed to public schools. Three more delegations of young scholars would follow a similar regimen over the next few years.

Initially, their Asian dress, language, and mannerisms caused such a sensation that they may as well have come from Mars as from the other side of the planet. The silk robes and long hair queues worn by the boys piqued curiosity everywhere they went. When they arrived in Springfield, their presence was seen as giving “quite a cosmopolitan look to the dining room of Haynes’s hotel and to our sidewalks as they mingle with the pedestrians of Main Street” (Springfield Republican, Sept. 25, 1872, p.4). In other host cities, inquisitiveness was not limited to mere gawking. The New York Herald reported on October 6, 1872 (p. 8) that “a New England lady was recently shown out of the dining room of the Chinese students in New Haven for examining too closely the young fellows’ pigtails.”

The students excelled in their studies. They attended the same classes and read the same books as their school mates. They participated in social activities and competitive sports. Their disciplined approach to academics resulted in an array of achievements. According to the New Haven Evening Register (July 15, 1880, p. 4), “The highest rank in the class graduating this year from Hopkins’ Grammar School was attained by a Chinaman, Yan Phou Lee.“ This same young man also won prizes in English and Greek composition. He and numerous other Chinese students later went on to earn degrees from Yale.

In accordance with strict instructions to cooperate in all aspects of the daily lives of their hosts, the students immersed themselves in the new culture. American habits surprised, but pleased them. One student expressed delight in his American house mother’s habit of frequently kissing his cheek. He stated wistfully that he could recall that only once had his stoic Chinese mother kissed him. The students quickly adapted to local ways. Dutifully they attended church services, cheerfully enjoyed popular entertainments, and willingly spoke to any group that wished to enhance their knowledge of Chinese tradition. That tradition, however, was rapidly becoming a phenomenon of the past for the young students.

As they assimilated into society, their flowing robes disappeared and their signature queues lay hidden beneath the latest clothing styles from New York. A number of the young scholars had converted to Christianity and become active participants in Congregational churches throughout the Connecticut Valley. Some had “run into the same excesses and are as apt to fall off in their interest in study as other boys who get into free and easy ways” (New Haven Evening Register, September 16, 1881, p. 1). Stories of smoking tobacco, playing poker, and even cutting their traditional queues reached the homeland. A secret inquiry was launched by Chinese officials. When the investigator arrived in Hartford, “he was shocked to find that the students, so far as outward appearances go, had abandoned the customs, habits and traditions of their country” (New York Herald July 31, 1881, p. 8).

Yung Wing’s innovative educational program was terminated immediately, and a recall of the students was issued. Seeing his hopes for China’s future disintegrate, Wing did his utmost to enable the boys to stay. The official order to return, however, was inexorable. A summons went out to host families throughout the Connecticut Valley; bags were hastily packed and the boys were gathered together from the towns and cities where they had been living. On August 21, 1880, they boarded trains destined for Boston where a ship waited to take them home. En route, two of the young students asked permission to disembark briefly in Springfield to say their goodbyes to American friends. Yung Kwai and Tan Yew Fun stepped off the train at the depot and that was the last the departing Celestials saw of their friends.

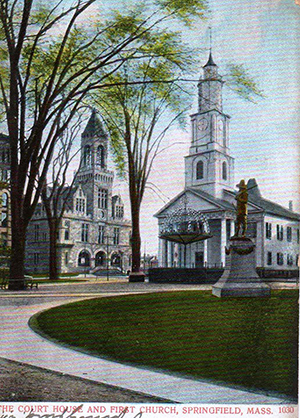

Both escapees were Christian converts. Yung Kwai had worshipped with the Vaille family in Springfield’s First Church. He viewed a “return to China as going to almost certain death” and hoped “to keep hidden for a year” until he could become a citizen of the United States (Springfield Republican, August 27, 1880 p. 6). Within a few weeks, friends of the fugitives hired a Boston lawyer who succeeded in arranging legal permanent residency in the U.S. for them.

The students who returned to China wrote to former host families of harsh punitive measures levied against them for their Americanization. One lamented to his Northampton contacts, “I wish I could return to dear philanthropic New England, where the teachers are better than mothers, where friends are better than sisters and classmates more agreeable than brothers” (New Haven Register, January 16, 1882, p. 2). Some did eventually return to New England. That is a story for another day; suffice it to say that in the long run, the entire delegation of the Chinese Educational Mission succeeded in fulfilling Yung Wing’s dream of escorting China into the modern world.